Hollywood's Obsession With 'Part Ones' Is Unhealthy – And There's One Clear Solution

Cinema has a wondrous, unmatched ability to take the dreams, fantasies, fears, and so forth of the artists who make movies and translate them into a medium where they can be shared by millions. Putting a lid on that ability is something one does not want to advocate for. Yet the film industry is a business, so naturally, some restrictions will occur. Fortunately, some of the greatest art of all time has been born of restriction; necessity is the mother of invention, as it were.

However, we are at a point in our cultural and economic status where everything has fallen out of balance. Things feel more restrictive than ever, and while financial backers are squeezing harder, creatives are pushing back and demanding more freedom, not less. A byproduct of this situation is the rise of the multi-part movie.

While the format (which is similar yet notably distinct from a sequel) is not new, the trend has exponentially grown; the last few years alone have seen a plethora of "Part" films being released, from "Dune: Part Two" to "Horizon: An American Saga: Part One." While epic, multi-part cinematic sagas can be incredibly rewarding to watch, they carry with them a worrying gamble: "Horizon: Part Two," which was scheduled for release in August, was dropped from Warner Bros.' release calendar due to the dismal box office of "Part One", with no new date announced. As such, where multi-part films used to feel creatively daring, they are beginning to resemble television a little too closely, running into the same hedge the medium often does in terms of suddenly stunted narratives.

Fortunately, there's one easy solution to help ease a good deal of this issue: stop treating multi-part films like sequels.

A brief history of the multi-part film

Although the multi-part film is undeniably a modern trend, it is also not a 21st-century invention. Austrian-American director Fritz Lang first broached the concept as early as 1924, with his two-part silent fantasy epic "Die Nibelungen." Sergei Bondarchuk's staggering adaptation of "War and Peace" for the Russian studio Mosfilm was released in very "Horizon"-like fashion, in four parts between 1966 and 1967.

Yet there's a key element both those early examples share; both "Die Nibelungen" and "War and Peace" were adaptations of an epic poem and an epic novel, respectively, and were narratives that best lent themselves to long-form storytelling. Thus, Lang and Bondarchuk made the best compromise possible between art and commerce, splitting up their films into multiple parts so that little of the work itself would have to be sacrificed while allowing the films to appeal to general audiences.

Though the multi-part film was never dormant for too long, it was generally employed in this type of adaptation situation. That's because other epic films found a happy format in the Roadshow. These are films structured like stage plays, with an Overture, Intermission, and so forth. Many classic film fans like myself have been openly hoping this format would make a comeback. Sadly, most modern multiplex chain theaters (AKA the majority of still-operating theaters in the country) are poorly equipped to handle such showings, as Quentin Tarantino's release of "The Hateful Eight" in 2015 proved.

How 'Kill Bill' paved the way for modern multi-part films

Speaking of Mr. Tarantino: he is conspicuously (if somewhat inadvertently) responsible for the issue regarding multi-part films we're currently facing. While multi-part adaptations of novels were kinda always a thing (more on that in a moment), it's Tarantino's fourth feature film, "Kill Bill," which proved to Hollywood that there was a whole new way to get an extra squeeze of a film's juice. Initially conceived and shot as one sprawling, epic saga of a woman's revenge, "Kill Bill" was split into two parts after noted criminal and producer Harvey Weinstein balked at Tarantino's initial cut of around three hours. (Ironically, thanks to the trend of so many blockbuster movies' run time inching closer to — or even right at — the three-hour mark, "Kill Bill: The Whole Bloody Affair" might have been released as a single film had it been made today.)

Thus, "Kill Bill: Volume 1" and "Volume 2" were released in 2003 and 2004, respectively, lending the film the feeling of a minor franchise and becoming Tarantino's only "sequel" to date. Therein lies the issue; neither "Volume" of "Kill Bill" is a film unto itself in the same way that all sequels are. Though, of course, watching each "Kill Bill" separately has a similar feeling to watching some sequels, it's when you watch the entirety of "Kill Bill" in one go that it becomes apparent how the movie was originally structured (and is best served) as a single film. Yet the damage was done; the Hollywood bean counters had already begun to crow about how much more money this strategy would make them, and the multi-part film suddenly became a lot more financially attractive.

The rise of the multi-part motion picture adaptation

Let's not forget the other early '00s series that made the multi-part film attractive to Hollywood: Peter Jackson's splendid adaptation of J.R.R. Tolkien's "The Lord of the Rings." The trilogy isn't really a multi-film adaptation, thanks to Tolkien writing and publishing each installment as three separate books. Yet Jackson and his collaborators did such an impressive job of making each movie of the saga feel satisfying, and the release schedule of one film per year for three years (along with the whole trilogy being largely shot back-to-back) made it feel like a more cohesive whole than, say, any one of the "Star Wars" trilogies.

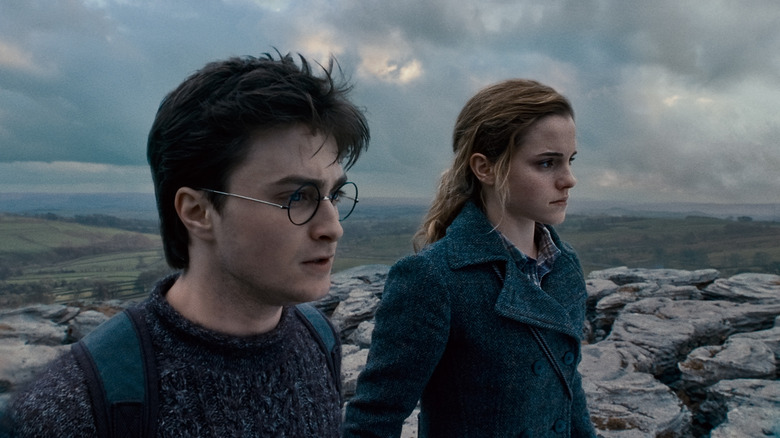

The success of "Lord of the Rings" was two-fold in terms of audience response: it made a potentially daunting, even alienating narrative much more palatable to new audiences, and it satisfied longtime fans' desire to see as much of their beloved story on screen as possible, with relatively few fans having tantrums over omitted storylines and characters. Thus, Warner Bros.' "Harry Potter" series took note, resulting in the seventh and final adaptation, "Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows," to be split into two films itself. Again, this wasn't new; producers Ilya Salkind, Alexander Salkind, and Pierre Spengler did the same to Richard Lester's film version of "The Three Musketeers" in the early '70s. Yet the rapturous fan response to allowing "Deathly Hallows" so much breathing room resonated with geek-friendly Hollywood, leading to further adaptations of installments of popular book series — "Twilight," "The Hunger Games," and even Jackson's follow-up prequel of "The Hobbit" — to be extended in their cinematic incarnations.

The trouble with 'It' and the death of 'Divergent'

While breathing room for an adaptation can, yes, be a generally favorable thing, it can also become detrimental. Take, for example, Andy Muschietti's adaptation of Stephen King's "It." While conventional wisdom believes "It: Chapter One" to be great and "It: Chapter Two" to be garbage, that's because so much of King's story is intended to be connected and not serialized or sequelized. It's in the immediate connection between the young and old versions of the protagonists that "It" gains its scope, a quality that a two-film release did not serve. While some of this can be rectified by watching both films back-to-back, a lot of the separation between the movies exists because they were conceived, written, and shot as sequels over a span of four years. No wonder some of the magic from that first chapter was lost.

At least "It" got to tell a complete story, unlike the sad case of the "Divergent" franchise. Although the "Divergent" book series was comprised of just three novels, the producers of the film series attempted to hop onto the "split the final chapter into two movies" trend, with part one, "Allegiant," released in March of 2016. Unfortunately, due to that film's underwhelming box office, the second film was revamped as a television movie before being canceled outright. Thus, anyone looking for a complete screen adaptation of the "Divergent" story is woefully (and, for now, forever) out of luck.

The fate of the proposed second chapter of "Allegiant" is not all that uncommon; not, that is, when you include television in a discussion that is ostensibly supposed to be about cinema. While there have been countless TV shows canceled after one or more seasons that never got to finish telling their stories, it's much more rare to have something like that happen in the world of films.

Turning film into television

Although there are certainly many films that leave the door open for a sequel that never materializes, the reason why this problem isn't the same for movies is that the sequel is, typically, a more or less self-contained story. Sure, you may not know who a certain character is if you skip, say, "Lethal Weapon 3" and go straight to the fourth film, but for a long time sequels were made with the assumption that the audience didn't need to "catch up."

Now, after decades of home media being a thing and artists wishing to experiment with long-form narratives, conventional wisdom is starting to erode. Enter: the behemoth narrative experiment of the Marvel Cinematic Universe, which contains multiple narrative threads throughout several franchises under one big banner.

As exciting as all of this can be, the effect it's beginning to have on cinema is that it's slowly turning into television. Much has been made of the prestige TV era and its debt to cinematic techniques; less has been said about the way film franchises have become dependent on audiences doing their homework. The rewards can be great, sure, but the trend is also contributing to the general flattening of culture, blending film and television together so much that they're almost indistinguishable from each other.

"Horizon" is the latest and most egregious example of this. While Kevin Costner's Western, once all four parts are released (the latter two having not even been shot yet), may end up resembling prior cinematic sagas like "Once Upon a Time in the West" and "Heaven's Gate," its piecemeal release feels more like a miniseries; "Part One" even "ends" with a lengthy preview of scenes to come in the next installment.

The solution: stop treating multi-part stories like sequels

There are a lot of ideas that Hollywood could workshop in trying to accommodate epic films again, but the easiest solution could turn out to be the most effective, and it's one that not just Hollywood but audiences can make happen right now: stop treating multi-part films as sequels. There are people out there who vociferously argue that "Kill Bill: Volume One" and "Dune: Part One" can be considered stand-alone films, but so many hoops have to be jumped through to make those justifications; the former is half a movie, and the latter is an adaptation of half of one book.

Although not everyone is annoyed about truncated stories in the same way, there is undeniably a difference between "James Bond/Thor/The Avengers Will Return" and "To Be Concluded." As many have said elsewhere, Hollywood might be learning that lesson sooner rather than later; not only are audiences rightfully annoyed that "Horizon: Part Two" has been delayed, while horror fans are rightfully confused as to what's going on with Renny Harlin's "The Strangers," but it seems that Universal's adaptation of the musical "Wicked," being released this November, isn't being marketed heavily as a "Part One," which it most definitely is. If people go into "Wicked" at least armed with the knowledge that they'll have to wait a whole year for the story's conclusion, perhaps they won't groan when "To Be Concluded" (or a trailer for "Part Two") acts as an "ending" to that film.

The future of possibilities for multi-part films

Of course, not treating these films the same way as sequels is only the first part, and will hopefully lead to them not being distributed like sequels, too. There are lots of fun experiments to try in terms of presenting a 3-hour-plus story on the big screen. Instead of bringing back the Roadshow format, what about this: something where, say, "Horizon" Parts One and Two were released on the same day, and could be seen separately or concurrently with some kind of ticket discount deal. Or what if the full "Horizon" experience could be seen in a single sitting (with intermissions) at select prestige theaters while the rest of the country could choose to see it in sections?

Leaving aside such pipe dreams, there are ways to address this issue that already exist. The original release schedule for "Horizon" was a decent idea to begin with (with some theaters providing a "Horizon Passport" ticket for both films that will now have to be refunded), and applying that again could work. Then there's the fact that, to paraphrase another Costner film, if you build a great three-hour epic, audiences will come in droves, as Christopher Nolan's "Oppenheimer" proved. There is a lot to be said about artists working within the restrictions of budget and running time, just as there's a possibility that the three-hour runtime limit could be stretched for the right filmmaker and the right project.

In general, I'm glad to see the epic movie alive and well, albeit in a format that it feels ill-suited for. I believe that, if we can reconfigure Hollywood's attitude toward multi-part films from them being de facto franchises into singular events, we could see some phenomenally fulfilling works of cinema going forward. Modern audiences are primed to see the cinema as the best place to witness spectacle and scope; I say let's give it to them, in the most creative way possible.