The Seven Funniest Marx Brothers Movies, Ranked

Brothers Leonard, Adolph, Julius, Milton, and Herbert Marx were born into a performing family. Their mother, Meine Shoenberg (known on stage as Minnie Palmer) was already the daughter of a ventriloquist and a professional yodeler, and their uncle was Al Shean of the comedy duo Gallagher and Shean, well known on the vaudeville circuit. Minnie Palmer encouraged her sons to perform; they had natural gifts for music and comedy, and would serve as their manager. Julius, the first to perform, made his stage debut in 1905. Leonard, Adolph, Julius, Milton, and Herbert would eventually adopt the stage names Chico, Harpo, Groucho, Gummo, and Zeppo, respectively, and the Marx Bros. would swiftly become one of the premiere comedy acts of their generation.

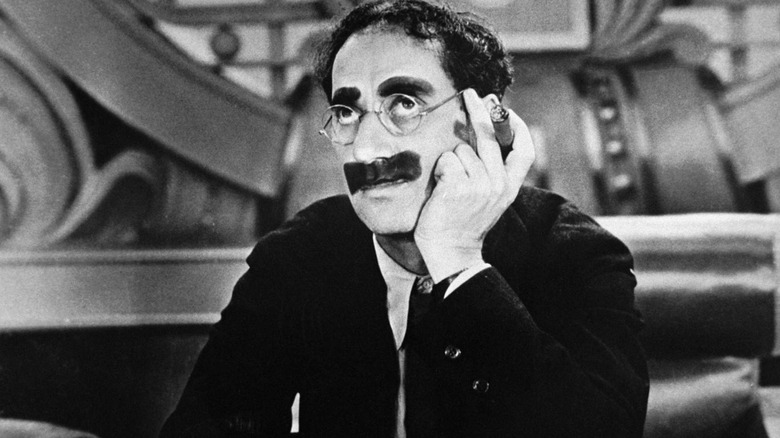

To this day, no comedian hasn't been influenced by the Marx Bros. Chico's charming conman, Harpo's innocent cartoon, and Groucho's wisecracking Lothario are seared into the pop consciousness in perpetuity, birthing everyone from Mel Brooks to Bugs Bunny.

In the 1920s, the Marx Bros. moved from stage to screen and, from 1929 until 1937, entered a hot streak, the likes of which cinema rarely encounters. The comedy films that the Marxes made with Paramount are among the best ever produced, and a few of the films they made with MGM (after Zeppo left the troupe to start a very, very successful engineering firm) are undeniably excellent. Gummo, incidentally, only performed with the troupe until 1918 when he went off to fight in World War I.

Those seven films are among the best comedies of all time, and ranking them is no easy feat. /Film shall endeavor to do so below.

7. A Day at the Races (1937)

The seventh film in the central Marx Bros. canon (not counting the unreleased and lost 1921 film "Humor Risk"), "A Day at the Races" is certainly no flop, but it also signaled something of a downturn in the Marx Bros.' cinematic output. On stage and in their earlier films, the Marxes were freewheeling and wild, using reality itself as an instrument on which to riff, jazz style, on every minutia of polite society. "A Day at the Races" is a lot more structured, featuring a solid screenplay with notable supporting characters and an actual plot. Perhaps a hair too much time is spent with the film's star couple played by Maureen O'Sullivan and her beau Allan Stewart.

When the Marxes do appear on camera, however, "A Day at the Races" comes alive. Chico, ever the con artist, distributes coded horse racing tips only to bilk his unwitting customer into buying multiple books just to decipher the codes. And, of course, Groucho and Margaret Dumont — as invaluable to the troupe as any of the Brothers — have excellent chemistry. "A Day at the Races" doesn't reach the sublime, near-abstract comic highs of their earlier films, even if it functions better as an actual movie.

6. The Cocoanuts (1929)

Their earliest surviving film, "The Cocoanuts," has the opposite problem as "A Day at the Races" in that it hardly coheres at all. The plot is ostensibly a crime story involving Chico serving as Groucho's shill, inflating the prices of worthless homes at auction, and the return of a valuable necklace to a wealthy socialite (Dumont).

Like a Tex Avery cartoon, however, "The Cocoanuts" is a mere thin premise on which the Marxes could hang their jokes. The jokes were interspersed with musical numbers, giving the film a live-stage feelings. Indeed, the musical numbers were filmed live in their entirety, with the orchestra performing simultaneously. "The Cocoanuts" has plenty of funny bits, including the famed "Why a duck?" joke, but it also feels like a strange marriage of cinema and stage that didn't quite emerge as either. It was, it seems, an attempt to capture the vaudeville bedlam of the Marxes on camera, but only partially succeeded. For those of us who always wanted to see the Marx Bros. perform live, this may be as close as we'll ever come.

5. Animal Crackers (1930)

"Animal Crackers" gets a lot of mileage from one of its opening songs, "Hooray for Captain Spaulding / Hello, I Must Be Going," one of the troupe's funniest musical numbers. Groucho plays Spaulding, an African explorer and guest of honor at a party thrown by Margaret Dumont. Groucho is doing his usual shtick, but finds himself in a position of prestige, throwing the Marx Bros.' central shtick into stark relief. Often, they play rascals and drifters, happy to prod the wealthy a-holes who horde wealth. If Groucho was one of them, however, he can mock the fact that he gets respect, even as he mercilessly hounds and berates his peers. "Animal Crackers" came very shortly after the crash of 1929, so mocking the rich was certainly in vogue ... and warranted.

The plot involves a missing painting. The Marxes are up close for the investigation, and the fact that they don't care makes "Animal Crackers" emerge as a satire of "The Rules of the Game" ... nine years before Jean Renoir made "The Rules of the Game." For the Marxes, the rules had to be broken before they could be obeyed.

If the name Captain Spaulding is familiar, it's because Rob Zombie used multiple Groucho Marx characters' names as the aliases of his murder family in "House of 1000 Corpses," "The Devil Rejects," and "3 From Hell." Sig Haig played Captain Spaulding, Bill Moseley played Otis Driftwood (from "A Night at the Opera"), and Tyler Mane played Rufus Firefly (from "Duck Soup").

4. Horse Feathers (1932)

The satire of the Marxes always worked best when it was pointed, and there was no riper target for their manners-free shenanigans than the realm of academia. "Horse Feathers" is one of the best college comedies ever produced, putting Groucho in a mortarboard, and Chico and Harpo as their usual freelance criminals (they work for a speakeasy when Prohibition was still in full swing) who, by the end of the film, will find themselves playing football for the film's central college, Huxley.

"Horse Feathers" not only mocks the uptight, stuffy world of higher education, but also the contrived plots of the era's many college comedies. If the plot doesn't cohere, the audience is never lost, as "Horse Feathers" skips trippingly through tropes, likely regurgitating familiar plot points. It's like the Marx Bros. are on the fringe of a real movie, invading every once in a while to make fun of it before retreating into their safe parallel dimension of chaos.

I would recommend watching "Horse Feathers" after Chuck Jones' 1942 short "The Dover Boys at Pimento University; or, The Rivals of Roquefort Hall," as they compliment each other perfectly, despite being made a decade apart.

3. Monkey Business (1931)

"Monkey Business" is essentially the version of "The Cocoanuts" that works. The plot is nonexistent and the scenario — the Marx Bros. are stowaways on a boat — is only a scant premise allowing them to do their signature shtick. It's worth noting that "Monkey Business" was the first film that the Marxes wrote specifically for the screen, and wasn't based on any of their stage productions, giving the film a freer, more natural feeling. By 1931, the Marxes knew the rules of cinema pretty well and had found a way to be themselves in a different medium.

And, boy howdy, are they funny. From the barrels singing "Sweet Adeline" to Harpo's giggling like a child, every joke lands with sublime timing. The films with Zeppo also tended to be stronger, as Zeppo could serve as the romantic protagonist while his brothers provided the slapstick. When an ancillary mating couple entered Marx Bros. films, they often felt like interlopers. Zeppo allowed the plots of their films to link directly to his charms (although for my money, Chico was the hottest Marx Brother, especially when he was shooting the keys at the piano).

Oh yes, and there's a kidnapping plot, but, again, watch "The Dover Boys" and you'll see that kidnapping plots were a dime a dozen, even as early as 1931.

2. A Night at the Opera (1935)

The world of high opera left its face completely unguarded as the Marx Bros. picked up a pie and threw it straight into its target. "A Night at the Opera" also features the best Margaret Dumont performance in a career full of amazing performances; seriously, the Brothers could not have functioned without Dumont as their "straight woman." "A Night at the Opera" is the troupe's most conventional piece of cinema, featuring a plot one can actually follow. Indeed, "A Night at the Opera" was strong enough to serve as the inspiration for the 1992 Marx pastiche "Brain Donors," with John Turturro playing the Groucho role, Bob Nelson filling the Harpo role, and Mel Smith occupying the Chico role.

"Opera" also features some of the troupe's funnier gags; this is the one with the hardboiled egg orders shouted — and honked — through the door of the stateroom. And yes, there are some legitimately great opera scenes. One gets the sense that the filmmakers respected the craft of Opera, just not the hoity-toity culture that surrounded it.

1. Duck Soup (1933)

"Duck Soup" features the sharpest political satire of any Marx Bros. film. While their body of work typically confronted uptight social mores and the strictures of class, "Duck Soup" goes so far as to mock politicians, the military, and the institution of war. Groucho plays Rufus T. Firefly, the leader of the nation of Freedonia. He had no beliefs and doesn't care for the pomp and circumstance attached to world leaders. Freedonia is teetering on the cusp of war with the nearby nation of Sylvania, whose cabinet rattles their sabers a lot.

By the end of the film, war has broken out, bombs are exploding, and the Marxes are firing weapons in their underwear. The entire war effort feels absurd and silly, pointing out that killing one another for something as piddling as your country is the ultimate in human folly. "Duck Soup" presents its satire, however, without a shred of sentimentality; it doesn't advocate for compassion like Charlie Chaplin's mawkish speech at the end of "The Great Dictator." It merely mocks us, the viewer, for wanting war in the first place. "Duck Soup" is slapstick wielded for a worthy cause. It's one of the best comedies of all time.