The One Stephen King Book That Will Never Get A Film Adaptation

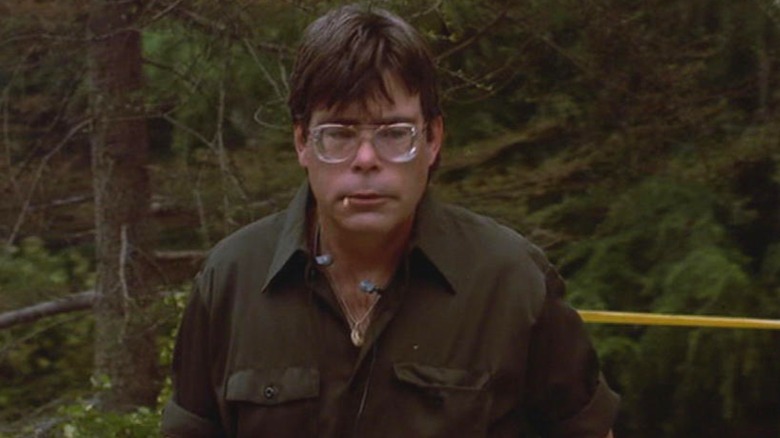

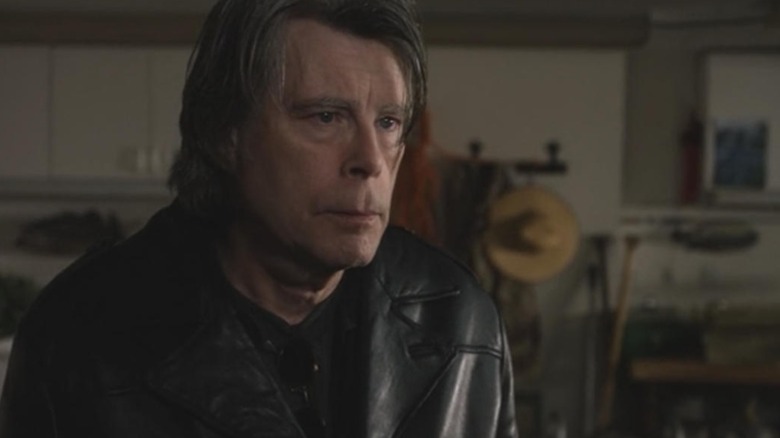

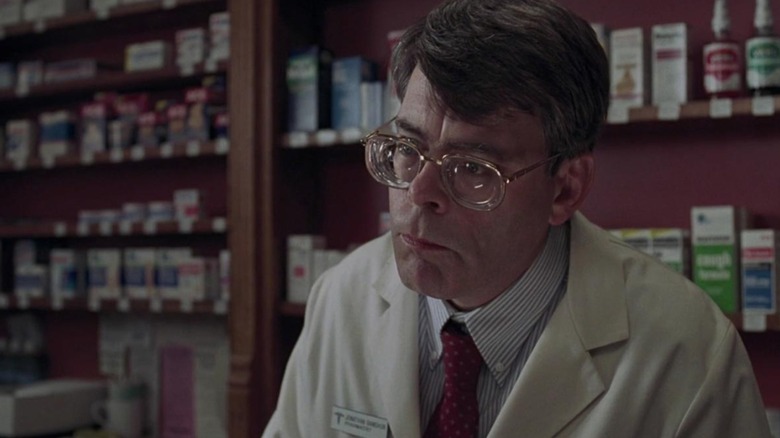

When it comes to sheer volume of movie adaptations under their belt, it's tough to find a working author with more cinematic dominance than Stephen King. The horror master continues to pump out new books on a yearly basis, and Hollywood keeps pace with movie after movie based on his best, most popular, and -– after years of mining from the cream of the crop –- even just-okay-est works. As of publication time, there are currently about a dozen King adaptations reportedly in the works, including Lynne Ramsay's spin on "The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon," Bryan Fuller's "Christine" remake, Osgood Perkins' "The Monkey," and the long-awaited "Salem's Lot" revamp from Gary Dauberman and Warner Bros.

At some point in the future, it seems likely that every King work ever written will get the big or small screen treatment. However, there's one book that's been absent from fan discussions about adaptations for years (and for good reason): "Rage." The author wrote the book when he was 18 and published it years later under the pseudonym Richard Bachman. By that point, King had already penned several 20th century classics, including "Carrie" and "The Shining," but "Rage" was different. It told the story of a school shooting from the shooter's point-of-view. When the controversial text started popping up in news stories about real shootings, King decided to let the book go out of print.

King pulled his early book, Rage, from shelves

The protagonist of "Rage" is a character named Charlie Decker, a high school senior who holds his classmates and teachers in a state of terror for hours on end, killing a teacher and inspiring mob violence before being shot by police. Like most King books, "Rage" leaves no psychological or social stone unturned, spotlighting Charlie's home environment, the casually racist and gender prejudiced attitudes of its time, and the medical and criminal justice systems the killer teen becomes a part of by the book's final pages. "Rage" is horrifying, but so are most King books. The difference between it and other texts it that it became linked to real-life school shooters, some of whom seemed to see it as a guidebook of sorts.

As King notes in his 2013 essay "Guns," the first hint that "Rage" was having ill effects came in April 1988, when a student in California brought a gun to school, firing shots that didn't hit anyone before admitting, "I don't think I can kill anyone." He was arrested and later stated that "Rage" was one of his inspirations. King cites three other school shootings and hostage situations from 1989 to 1997 that led to his eventual choice to stop printing the book. All three boys who were responsible had read "Rage," with one seemingly acting out the book's storyline and another paraphrasing a quote from the text after killing three people. "That was enough for me," King wrote, noting that at the time he only knew that two incidents related back to his book. "I asked my publisher to pull the novel from publication."

King equated the book to an accelerant in the hands of firebugs

King wrote that pulling "Rage" wasn't easy, as the book had been included in a popular collection of four pseudonymous works titled "The Bachman Books." It's still possible to find a copy today –- my mom had one on her shelf when I was growing up –- but King is clear in his assertions that it's not worth keeping around when it actively did real harm. "My book did not break [the readers in question], or turn them into killers," King wrote in "Guns," noting elsewhere in the essay the ease with which the killers accessed guns, their fractured home lives, and the intense mental illness some of them were already experiencing in their teens. He continued: "They found something in my book that spoke to them because they were already broken. Yet I did see 'Rage' as a possible accelerant, which is why I pulled it from sale. You don't leave a can of gasoline where a boy with firebug tendencies can lay hands on it."

King's decision remains one of the most thoughtful and measured acts of what some would call "self-censorship" in recent memory. The author doesn't oversimplify the issues surrounding school shootings, nor does he consider pulling the book a cure-all. The essay even acknowledges the ways in which anti-gun control activists use pop cultural violence as a scapegoat to avoid more pressing legislative issues. There's no way to measure how many school shootings didn't happen because of King's choice, but it obviously didn't hurt. In addition to the true stories cited in his essay, at least two other '90s shootings appear to have been inspired at least in part by "Rage," with one student even killing his English teacher after she gave him a low grade on an essay about the book (via U.S. News & World Report).

Would a Rage adaptation even work, anyway?

With its lengthy, horrifying history in mind, it seems unlikely that "Rage" will ever get a big screen adaptation, and that's perfectly fine. In 2017, I wrote that "Rage" could likely only exist on screen in cultural documentary form, positing that it could work with a director like "Casting JonBenet" and "The Assistant" filmmaker Kitty Green -– who has a knack for interrogating what a movie should show us within the movie itself –- behind the camera. Meaningfully good movies about school shootings are rare, but they do exist. "We Need To Talk About Kevin," "Mass," and "Spontaneous" have all addressed the issue in the years since "Rage" went out of print, but all three cleverly do so through creatively indirect means. They don't focus on the killer's internal monologue or the violence of the event itself, but on fantastical allegory, muted aftermath, and the impressionistic fragments of a sinister childhood.

King seems to have never spoken directly about the idea of a "Rage" adaptation, but he hasn't had to. Occasionally, the idea of a movie adaptation comes up on fan forums, and it quickly answers itself: The author's decision to pull the book was a sound one, and there's no reason to keep the story alive in any form after he's already had the last word. "Rage" is no longer on shelves, and "Guns," released in the wake of the Sandy Hook massacre, raised plenty of money for gun safety charities. King called for a ban on assault weapons in the piece, but a decade later, America's lawmakers still seem to care more about guns than kids. By actively choosing to take an object that had been weaponized out of the hands of vulnerable young people, King made the right choice. Whether or not everyone else will remains to be seen.