Al Pacino Improvised A Classic Moment In Dog Day Afternoon

There were bigger movie stars than Al Pacino in the 1970s, but between 1971 and 1975, he gave six utterly electric performances that placed him in the American film acting stratosphere alongside the likes of Marlon Brando, Dustin Hoffman, Jack Nicholson, and Robert De Niro. And as brilliant as those guys were, the virtuosity on display in "Panic in Needle Park," "The Godfather," "Scarecrow," "Serpico," "The Godfather Part II" and "Dog Day Afternoon" made a solid case for Pacino as the best of the bunch. He could be seductive, sympathetic, vulnerable, pathetic and terrifying –- sometimes all in the same movie. And his peers were dazzled enough to nominate him for four straight Oscars.

The full range of Pacino's genius can be found in Michael Corleone's journey from principled World War II returnee to brother-killing monster, but for sheer thespian fireworks, you can't top his live-wire portrayal of bank robber Sonny Wortzik in Sidney Lumet's "Dog Day Afternoon." Sonny possesses the bluster and ferocity necessary to strike fear in the employees of the First Brooklyn Savings Bank, but proves every bit the amateur when it comes to planning and follow through. When Sonny realizes they've arrived after the day's cash pickup (a sizable score that would've covered the cost of gender-affirming surgery for his lover Leon), he panics, drawing the presence of the cops and rendering inevitable his arrest.

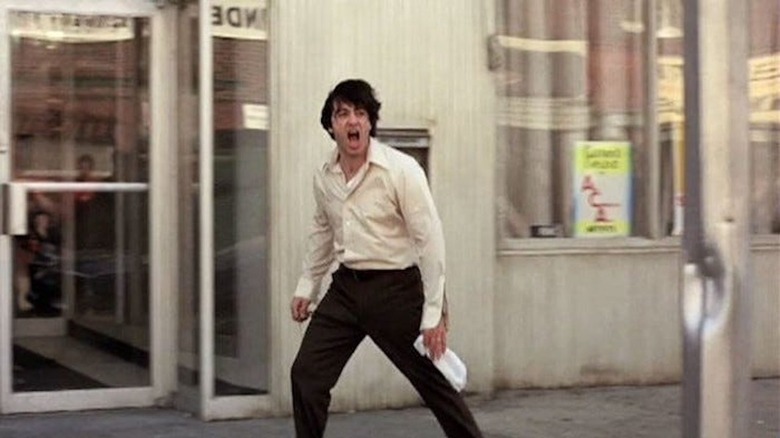

Sonny refuses to accept his fate, and, realizing he has a rapt audience not just of cops but fascinated Brooklyn bystanders as well, decides to play to the crowd. For several hours on a hot August day in New York City, Sonny puts on one hell of a show. He's thrillingly unpredictable, and his skittish, improvisatory performance brought out Pacino's boundless gift for invention, most notably in the film's famous "Attica" scene.

A caged Sonny turns righteous to win the crowd

In a fascinating, career-spanning interview with New York Magazine's David Edelstein from 2018, Pacino revealed that his "Attica, Attica" outburst was an in-the-moment ad-lib that came from one of the production's assistant directors.

The scene in question finds Sonny, having released a hostage as a show of good faith, holding a face-to-face negotiation with NYPD Sergeant Eugene Moretti (Charles Durning) outside of the bank. Moretti makes it plain to Sonny that he has scarce leverage and no hope of escape; he points to the snipers lining the area's rooftops, and tries to convince Sonny that, since he hasn't harmed anyone, he'll only do five years. Sonny knows the armed robbery charge itself will put him away for much longer than that, so, as the cops keep trying to close in on him (much to Moretti's frustration), he starts shouting "Attica" in reference to the 1971 Attica prison uprising (prompted by the facility's inhumane living conditions).

And this out-of-nowhere bit of movie magic only happened because a clever AD got in Pacino's ear before he walked out in front of the cameras.

There was once an organic method to Pacino's screaming

As Pacino told Edelstein:

"[The AD] says, 'Say 'Attica.' I said, 'What?' He said, 'Go ahead. Say it to the crowd out there. 'Attica.' Go ahead.' So I sort of half got it, so when I got out there, I looked around. This is on-camera now. Cameras are rolling, and I looked around, and I just said, 'Hey, you know, Attica, right?' ... And we start improvising, and you get that whole Attica scene, because an AD whispered in my ear as I'm going out a door. I mean, that is what movies are."

Some of our favorite movie moments are the product of such left-field inspiration, and it's a testament to Lumet's actor-friendly process (which involved ample rehearsal time akin to prepping a stage play) that Pacino and the AD felt the freedom to try something so wild on a shut-down Brooklyn street (because it costs a good bit of money to close down an area of a bustling metropolis for multiple days). This scene remains one of the go-to clips in Pacino's filmography, one that's spawned sincere homages and jokey references in everything from "Airheads" to "It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia." Five decades later, it's a reminder that, once upon a time, there was an organic method to the man's screaming histrionics.