The Best Captain America Story Ever Is The Perfect Gateway Comic

It's not news that, for the most part, superhero movies haven't made audiences into regular comic book readers despite publisher efforts. If anything, it feels like the problems that have plagued the superhero comic duopoly are seeping over into Marvel Studios' blockbuster behemoth.

Some critics have gone so far as to say comics will never be the primary medium for superheroes again. Ritesh Babu writes, "To entire generations of children, the superhero is an entity of the screen, not the comics page." I'll admit, I'm proof positive of this hypothesis. I first met superheroes through movies, cartoons, and franchise encyclopedias with years of comic story bullet points and trivia all contained in one binding. (Such tomes are useful at convincing young fans that superhero stories are a historied mythology to be revered.)

I was never opposed to reading comics — in middle school, I gradually collected a handful of '80s "Spider-Man" issues and electrifying one-shot "X-Men: God Loves, Man Kills." But trying to stay up-to-date on current series, as a child in a town without a local comic shop, was just too much of a headache.

I came to the Marvel Cinematic Universe as a Marvel fan, but not so much from actually reading comics; just reading about them. Until 2014 and the first Marvel movie of that year "Captain America: The Winter Soldier." I knew this was an acclaimed comic arc and the twist of Cap's old sidekick Bucky Barnes being the titular villain. When I like something, I want to experience as much of it as possible. So, I bought "Captain America: Winter Soldier" by Ed Brubaker, Steve Epting, and Michael Lark and then kept collecting each paperback volume, trade by trade. Those books taught me how comics aren't just homework to better understand and predict superhero movies — they can be great all on their own.

Captain America: The Winter Soldier is not a typical gateway to Marvel

Due to the success of "The Winter Soldier" movie, the comic often gets thrown out as a regular addition in "where to start reading comics" lists. Brubaker's "Captain America" is to this day usually recommended as the "Captain America" to start with. Since fans already know the basics from the movies, it'll be a smooth transition.

I won't disagree — "Winter Soldier" is great and it hooked me — but this does amuse me because it's not a story that fits the usual parameters of a starter comic. Usually newbies get handed books like "Watchmen" or, for the regular Marvel/DC characters, "Batman: Year One," self-contained books that can act as a "beginning" for the titular character. Marvel Comics leaned into that in 2012 with its "Season One" series, 140-or-so-page graphic novels that retold classic superhero origin stories with modern art.

"Winter Soldier" is not like that. It's a story that pulls every piece it can from the history of "Captain America" and casually throws out references. Ed Brubaker grew up reading Cap comics and it shows in his writing. (Issue #7, drawn by John Paul Leon, is all about the last days of Cap's retired sidekick Jack Monroe, who winds up murdered by the Winter Soldier and framed for a terrorist attack.)

Even the hook of the story — Cap's dead sidekick comes back as a villain — is rooted in past stories. After Captain America was reintroduced (and Bucky killed off) in 1964's "The Avengers" issue #4, the guilt of his partner's death weighed heavily on Steve Rogers for four decades. Bringing Bucky back was a radical choice that uprooted decades of status quo.

Now this revolutionary story is held up as the best beginning for a fresh-faced reader because it's just that good.

What makes Captain America: Winter Soldier so good

I knew all the twists of "Winter Soldier" before I ever read it. So while I can't speak to its quality as a mystery, I can promise that it's a top-notch espionage thriller. Like his later work on Garth Ennis' war comic "Sara," Epting's line-art has realistic backgrounds and character designs. Colorist Frank D'Armata's work isn't muted but the comic's palette is chosen to help keep the art down-to-earth. (Flashback scenes between Cap and Bucky are rendered in greyscale, a rather cinematic color-coding choice.)

Case in point: the comic's first big splash page is a realistic drawing of a New York City skyline but with Cap, in full red-white-and-blue, leaping in from the right edge of the panel. Strap in as comic book pulp comes together with "24" post-9/11 spycraft.

Captain America's nemesis, the Red Skull, is mysteriously murdered at the end of issue #1. Unfortunately the good news ends there, because the Skull's Cosmic Cube (you MCU fans might know this as the Tesseract) was swiped. The Cube's power is pure power — holding it, one can reshape the world however they want.

Cap, working alongside SHIELD (specifically his ex, Agent 13/Sharon Carter) spends the story slowly putting together the pieces, both of the threat in front of him and forgotten scraps of his past. That culminates in the horrible revelation halfway through that the Winter Soldier is an amnesiac Bucky, so the story's second half is about a desperate Steve Rogers trying to keep the faith that his friend isn't just a walking dead man.

The movie's handling of this dynamic is good; you can tell why the shippers zeroed in on Steve/Bucky, and it's not just because Chris Evans and Sebastian Stan are so hot. But the film is too crowded to make Bucky its core. The story is best experienced over many chapters.

The villains and politics of Captain America: Winter Soldier

Captain America is not just a character, he's a symbol. Different writers/artists use him to contrast what they feel America should be with what it is. After all, Jack Kirby and Joe Simon first drew him punching out Hitler because they were aching for the U.S. to do exactly that. ("Captain America Comics" #1 ran in 1940, before America entered World War II.) Brubaker's Captain America is as always a good person, but also a grimmer man of action; he's introduced training and Sharon notes he's been acting angrier than usual lately. Basically, Cap's mood is the same as the national one was in 2004.

The mastermind of "Winter Soldier" is KGB agent turned energy CEO Aleksander Lukin. The protégé of Soviet Colonel Vasily Karpov, the man who created the Winter Soldier, Lukin uses Bucky's iron fist as his own. Lukin's character is allegorical for Russia's post-Cold War transition from a communist state to a capitalist one.

The comic's very first scene is Lukin executing the Red Guardian, the Soviet counterpart to Captain America, killing a vestige of the old Russia. Then, the comic's last page reveals the Red Skull used the Cosmic Cube to escape death by putting his mind in Lukin's body, Mr. Hyde-style. Scratch a mega-capitalist's surface and you'll find a fascist. While Captain America is a hero of conviction, Lukin is a chameleon who wears different ideological coats over self-interest.

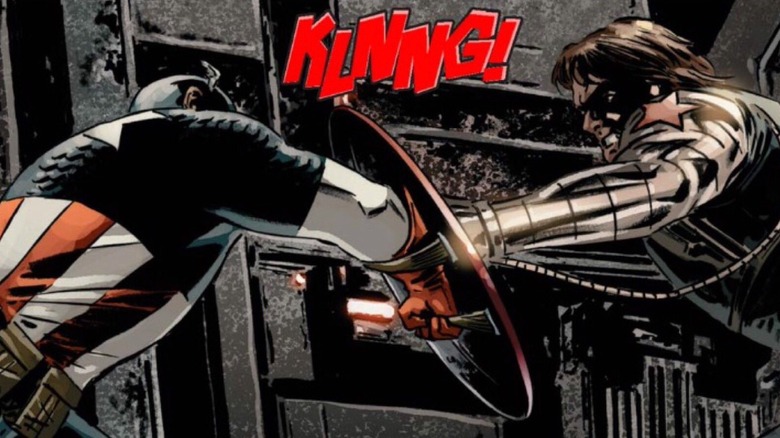

The villain who people really remember, though, is the Winter Soldier himself. This comic is the first time Bucky was ever cool and so much credit for that goes to his new look designed by Epting. The Winter Soldier's MCU look is a near recreation of his comic design because you can't improve upon perfection.

"Winter Soldier" (character and story) had all the potential of a failed experiment, but Brubaker and his artists knew how to thread the needle of risk.

Ed Brubaker's Captain America is more than The Winter Soldier

Brubaker and Epting's time on "Captain America" run does not end with the 13 issues that make-up "Winter Soldier." Next comes "Red Menace" (about Cap looking for Bucky while the Red Skull's daughter Sin and her lover Crossbones paint America red) and then "The Death of Captain America." In "Captain America" #25 Steve Rogers, being taken to trial after the "Civil War" event, is shot outside the courthouse on the Red Skull's orders.

Bucky turns the arc's title into a misnomer. Bequeathed the Captain America title and costume in Steve's will, Bucky becomes the book's main character and a far more burdened hero. Meanwhile, the Red Skull is looking to lay stake on the country his nemesis defended by using Lukin's wealth to buy himself a faux-populist presidential candidate. Steve's murder came at the right time; the 2008 financial crisis killed off the last simpering husk of the American dream, so of course Captain America dies when the nation is brought low. Brubaker's run asks if it can climb back up. To that, I'll never forget the last page of the arc's penultimate chapter ("Captain America" #41), where Bucky leaps into action and declares at last, "I'm Captain America!" It's a page I can somehow hear and its never left my mind's eye.

Now, I stopped reading for a bit after "The Death of Captain America" because I knew Steve Rogers would be coming back. Did I want to see the story that had thrilled me reverse course? In the end, my curiosity gave out and I finished Brubaker's "Captain America" across all its peaks and valleys.

The end of Ed Brubaker's time with Captain America and the Winter Soldier

This is why I think "Winter Soldier" and its sequel arcs make a fine gateway for comic readers. I understand the simple appeal of "Season One" stories, but those don't capture the messy experience of what reading most superhero comics is like. Marvel and DC stories aren't packaged together so neatly and I understand why that's off-putting. If you want proof that a sprawling, sometimes circular series that builds on decades of past work can still be a satisfying reading experience on its own, you need a great core story to anchor you. "Captain America" by Ed Brubaker was that for me.

Brubaker wrapped up his "Captain America" epic in 2013 with a "Winter Soldier" series, starring the no-longer-Captain Bucky and his lover, Natasha Romanoff/The Black Widow. In the last issue, a brainwashed Widow loses her memory and asks "Who the hell is Bucky?", i.e. the same words the Winter Soldier once asked a disbelieving Steve Rogers. When a comic has gone on long enough to be self-referential, it's a good sign to close up.

These days, Brubaker has taken a permanent hiatus from superhero writing; he's refocused on creator-owned crime comics, mostly drawn by artist Sean Phillips. (They're turning their "Criminal" series into a Prime Video TV series.) He's also voiced displeasure with how Marvel has compensated him and his artist colleagues for creating the Winter Soldier. However, reading his later work you can tell his experiences at Marvel haven't left him. Brubaker isn't writing superheroes anymore but they're not out of his system.

Ed Brubaker's creator-owned comics are must reads

In 2013, Brubaker and Epting reteamed for a new series at Image Comics: "Velvet." Set in the 1970s, the 15-issue comic follows the adventure of secret agent Velvet Templeton who, like every super-spy ever, has been framed for murder and is being hunted by her own agency. Brubaker has admitted that he was aiming for a spy movie tone when writing "Captain America" — "Velvet" lets him do so again without any of the superhero fluff. Brubaker said his goal with the series was a spy story that mixed the layered schemes/backstabbing of a John Le Carré novel with the awesome action and sensuality of a James Bond movie. My word, does he pull it off.

From 2016-2018, Brubaker and Phillips published 20 issues of "Kill or Be Killed" at Image. College student Dylan survives a self-harm attempt, but afterwards starts seeing visions of a demon telling him he must balance the scales by killing others. Otherwise, his life is once more forfeit. So, Dylan decides to become a masked vigilante and ensure the people he kills are ones who "deserve" it. The book suggests the demon is probably a hallucination, but that provides no safety for Dylan's targets or ultimately himself.

The premise of "Kill or Be Killed" has superhero DNA baked in: Brubaker called it a mix of "Death Wish" (the gun-wielding vigilante), "Breaking Bad" (a slow descent into evil), and "Spider-Man" (Dylan is keeping his masked crime-fighting a secret from his loved ones). Dylan even wears a red mask and has the semi-supernatural tragic origin story that any superhero does.

Pulp is Ed Brubaker's most revealing work

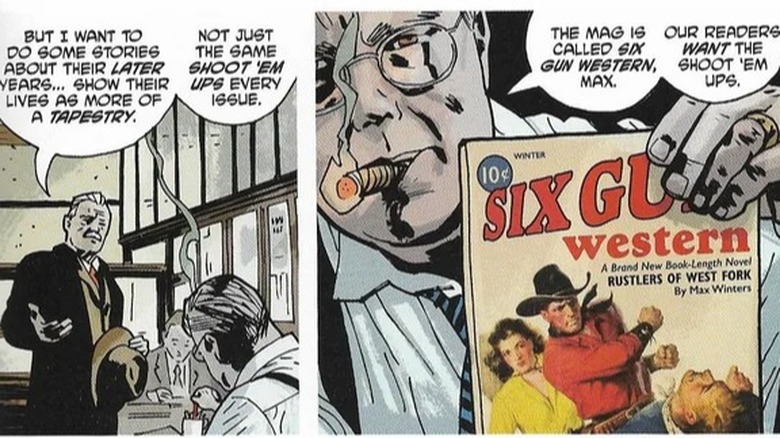

Brubaker's most hard-hitting work is the 2020 one-shot graphic novel "Pulp" (drawn by Sean Phillips, colored by his son Jacob Phillips). Set in 1939 New York City, "Pulp" follows former cowboy gunslinger Max Winter who has become a pulp fiction writer. Specifically, he writes schlocky Westerns loosely based on his real exploits, selling his life stories for penny's worth (two per word, precisely.)

The comic weaves in flashbacks to Max's younger days, with sunset-tone shading and colors that often don't quite fit within the line art. The effect literally looks like crinkly pulp paper, reflecting how the border between Max's memories and his lies is blurring. Tellingly, in the present day scenes, the coloring is much neater and more subdued.

"Pulp" is a thrilling Western, with an ending that's pure "Unforgiven," but it's really a story about writers, especially those who work in comics. One of the first scenes is Max in a row with his editor Mort (a possible reference to Mort Weisinger) over pay rates and creative risks. While Max wants to try something new, Mort insists on sticking with what sells. In their next meeting, Mort reveals he's hired his nephew to write new stories with Max's characters; this must be a familiar experience for anyone who's ridden the revolving door of talent at Marvel.

"The Winter Soldier" made me a bigger comics fan, but more importantly it made me an Ed Brubaker fan. If you're curious to read comics, then don't follow the continuity like many internet reading guides suggest, follow the creators — writers and artists both. If and when they leave the realm of superheroes, journey with them and let them surprise you.