The Stephen King Alter-Ego That Inspired A George Romero Horror Movie

Stephen King can't stop. The best-selling horror novelist is nothing if not prolific, churning out books on a steady, unstoppable pace for decades now. For years, King said in interviews that the only days he didn't write were Christmas and on his birthday. Later, he admitted that was a lie — he wrote on those days, too. When you write that often, you produce a lot of work. But as King's career began in earnest following the publication of his debut novel "Carrie" in 1974, the publishing world had a curious rule: authors should only publish one book per year. That wasn't good enough for King — he wanted more.

"I've been asked several times if ... I thought I was overpublishing the market as Stephen King," King wrote later. "The answer is no. I didn't think I was overpublishing the market ... but my publishers did." King struck upon a solution to publish more than one book a year: a pen-name. At first, King wanted to use the name "Gus Pillsbury," which was the name of one of his grandfathers. Eventually, he settled on Richard Bachman — "Richard" pulled from author Donald E. Westlake's pseudonym Richard Stark, and "Bachman" from the band Bachman–Turner Overdrive. Bachman even had an entire backstory: when he wasn't writing, Bachman was a New Hampshire chicken farmer. He also had a wife, Claudia Inez Bachman. "The Bachmans had one child, a boy, who died in an unfortunate accident at the age of six (he fell through a well cover and drowned)," King said. "[A] brain tumor was discovered near the base of Bachman's brain; tricky surgery removed it."

The concept of Bachman allowed King to conduct an experiment and see if books without the Stephen King brand name would be as successful as those with his moniker slapped across the front cover. Predictably, the original Bachman books — "Rage"(1977), "The Long Walk" (1979), "Roadwork" (1981), and "The Running Man" (1982) — were not blockbusters. "The Bachman novels were 'just plain books,' paperbacks to fill the drugstore and bus-station racks of America," King wrote. "This was at my request; I wanted Bachman to keep a low profile. So, in that sense, the poor guy had the dice loaded against him from the start."

And then King, as Bachman, published "Thinner" in 1984. And someone finally made the connection. Richard Bachman's days were numbered.

Richard Bachman's Thinner

Up until "Thinner," the Bachman books did not seem very Stephen King-y, at least in terms of story. While two of them, "The Long Walk" and "The Running Man," dealt with the fantastical in the form of being dystopian sci-fi novels, "Rage" and "Roadwork" were adult dramas grounded in reality. "Thinner" was different. The book dipped into the supernatural, telling the story of an overweight lawyer who suddenly starts wasting away after being cursed. King even not-so-subtly mentions himself in the book. And while the previous Bachman books didn't exactly move the needle, "Thinner" became a modest success.

And with that success came questions, and accusations. Who was this Richard Bachman guy? King didn't exactly do a good job covering his tracks. For one thing, the bulk of the Bachman books were dedicated to people King knew. For another thing, the books, especially "Thinner," stuck to King's style of writing. And that's when Stephen P. Brown entered the picture. Brown was a bookstore clerk in Washington, D.C., and he had a sneaking suspicion about the Bachman books. "My involvement began while I read Bachman's five novels," Brown wrote in the Washington Post. "Gradually it dawned on me that they could have been written only by one man, and it wasn't Richard Bachman. It had to be Stephen King."

To prove his hunch, Brown headed to the Library of Congress and checked the copyrights on the Bachman books. All but one of them were registered to Kirby McCauley, who was King's agent at the time. That might've been enough to blow the lid off the whole thing, but then Brown saw that the copyright for the very first Bachman book, "Rage," was in King's name. There was no hiding it: Richard Bachman was Stephen King. Brown sent King a letter revealing he knew the truth. He expected to be ignored. Instead, he got a phone call. "Steve Brown? This is Steve King," the voice on the other end of the phone said. "Okay, you know I'm Bachman, I know I'm Bachman, what are we going to do about it? Let's talk."

Stephen King's The Dark Half

The cat was out of the bag: Brown would pen a story about the pseudonym for the Washington Post, complete with quotes from King, his agent, and others who knew the truth. King was planning on publishing his next book, "Misery," under the Bachman name, but now that Bachman was revealed, that changed. Instead, King killed Bachman off — at least for a time.

But Richard Bachman never really left Stephen King's mind. And Stephen King, being Stephen King, decided to write about it. In 1989, King published "The Dark Half," a weird, violent novel about an author's pseudonym that comes to life and starts killing people. In "The Dark Half," things are reversed — the "real" author, Thad Beaumont, is a modest success while his pen-name, George Stark, is a bestselling author of a series of violent crime novels. When Stark's real identity is discovered, Beaumont kills him off. Unfortunately, Stark somehow becomes flesh and blood and begins murdering people close to Thad. He even violently kills the guy who outed Beaumont as Stark, which makes you wonder what Stephen P. Brown thought of the whole thing.

Like most King novels, "The Dark Half" was a hit — the second-best-selling book of 1989, in fact. And, like most King novels, a movie adaptation was inevitable.

George A. Romero's The Dark Half

George A. Romero and Stephen King had a good working relationship. King had a cameo in the Romero movie "Knightriders," Romeo directed the King-scripted anthology flick "Creepshow," and "Tales From the Darkside," a horror TV show created by Romero in 1990, featured two episodes adapted from King stories. But what Romero really wanted to do was tackle a King novel. "I've always wanted to make a novel of Steve's into a film," Romero told Fangoria (via the book "Creepshows"). "So many people have tried but failed to either comprehend or retain his voice and intention. Maybe that will happen to me too. But I've always wanted a crack at it."

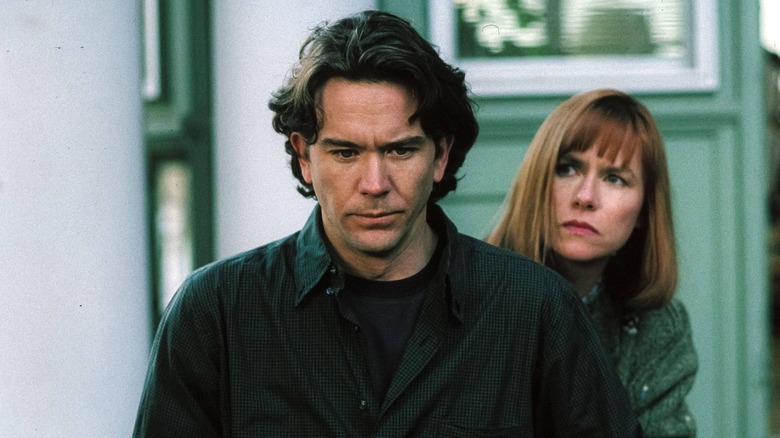

Romero had been floated to direct both "Pet Sematary" in 1989 and the "It" miniseries in 1990, but was unavailable for both. His opportunity came with "The Dark Half." Romero usually worked outside the studio system, but "The Dark Half" saw him working with Orion Pictures. "I have to respect the fact that it's their money," Romero told The Pittsburgh Press in 1990. The film itself remains mostly true to King's novel — "I've tried to be as faithful as possible to the book," said Romero, who penned the script. Timothy Hutton plays both Thad Beaumont and George Stark, and the actor is quite good in the Stark role, really relishing playing such a villainous character (aided by some gooey makeup — Stark's face begins to rot as the film progresses).

As for the film, it's mostly serviceable. The grand finale, which involves a huge flock of sparrows picking Stark apart, is a show-stopper, but this is a mostly middle-of-the-road Stephen King adaptation. And sadly, it got caught up in some behind-the-scenes woes. Distributor Orion was in dire financial straits at the time, and while Romero wrapped shooting in 1991, "The Dark Half" wouldn't hit theaters until 1993, at which point it flopped at the box office.

As for Richard Bachman, like George Stark, he, too would rise from the grave. While King had "killed off" Bachman, two more Bachman books would eventually hit the shelves, with the explanation being that there were previously unpublished Bachman stories that had been "found" by Bachman's fictional widow. There was "The Regulators" in 1996, and "Blaze" in 2007. As of now, it seems like Bachman is gone for good. But you never know ... he might pop up again.