Stephen King Created Pennywise Out Of An Innocent Children's Tale

One of the reasons "It" by Stephen King is such a scary book is that King sort of cheated. Why write one scary monster, he seems to have asked himself, when you could write a dozen different monsters and make them all the same guy? Although the clown persona is definitely the one that's stuck around the strongest in pop culture, the mysterious It, otherwise known as Pennywise or Bob Gray or The Eater of Worlds, takes a different shape depending on which kid he's trying to prey on.

When he's preying on germaphobe Eddie, he's an infected leper. When he's preying on Mike, he takes the shape of a bird from a movie that recently scared him. He's even seemed to have taken the shape of regular humans or possessed their bodies; such was the case with Beverly's abusive father in the book, who makes the jump from physically abusing her (in a way that could be denied if Bev ever tried to report him) to actively trying to kill her in public. It's the sort of thing that makes you wonder just how exactly these kids have survived for so long throughout It's latest return from hibernation, considering It can basically show up at any time in any form.

For King, the inspiration came back in 1978, when he was busy writing his other infamously massive novel, "The Stand." He was walking on a bridge when a well-known children's tale popped into his head. "I thought of the story of Billy Goats Gruff, the troll who says, 'Who's that trip-trapping on my bridge?' and the whole story just bounced into my mind on a pogo-stick," he explains in the book "Stephen King: A Complete Exploration of His Work, Life, and Influences" (via Entertainment Weekly). "Not the characters, but the split time-frame [...] all the monsters that were one monster [...] the troll under the bridge."

King's not the first to take inspiration

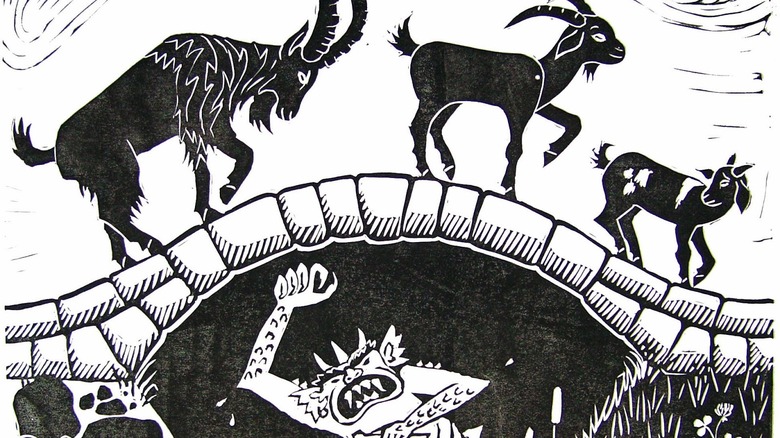

"Three Billy Goats Gruff" is a very old, influential children's story from Norwegian oral folklore. It was written down and first widely published in 1841, but the story was likely told to kids far earlier than that. The tale's about three billy goats who cross a bridge, the smallest going first and the largest going last. The troll under the bridge threatens to gobble up each of them, but the first two goats tell him to wait for the third one, as he's the biggest meal of them all. So the troll waits for the biggest goat, only for said goat to easily overpower him:

"He flew at the troll, and poked his eyes out with his horns, and crushed him to bits, body and bones, and tossed him out into the cascade."

There are many different versions of this story, each of them varying depending on whatever lesson the narrator wants to teach. Sometimes there are a bunch of monsters under the bridge, sometimes the monster is Death himself, and sometimes the first two billy goats aren't so lucky. See also: the version of the story taught to kids in the "Harry Potter" universe:

The connections to "It" are pretty clear, too. Not only does King have his monster attack multiple people at different times, but he also leaves the readers with the lesson that the best way to stop It is to fight back. Don't be afraid of him, don't try to run away; if you face him head on you'll have a much stronger chance. It is scary, sure, but much like that over-confident troll, he's mostly only scary if you think he's scary. Thoughtless confidence goes a long way.

What is Pennywise if not a troll under a bridge?

You can also see the troll's influence in It's usual modes of attack. He's a creature who dwells in the sewers, the pipes, the rivers, and (in the case of the novel's second kill sequence) under the bridges. The farther down you go, the more likely you are to encounter It, which means the best way to keep your kids safe in Derry is probably to get a house near the top of a hill. (Note: this likely won't work either.)

Like the troll, Pennywise also operates under a strange logic that's surprisingly consistent, even at his own expense. By feeding off his victims' beliefs that he's a scary monster that will eat them, he also forces himself to abide by the kids' beliefs that things like a silver bullet in a slingshot could genuinely harm him. Belief goes both ways, it turns out, which is why a thousands-year-old interdimensional alien such as It can be defeated through childlike imagination.

It's death is kind of silly in both King's original book and its movie adaptations, but spiritually it's very true to the folktale's version of events. If the troll under the bridge could be tricked by the first two goats' questionable (but firmly held) logic, then so could America's least favorite clown.