One Underrated Twilight Zone Episode Is A True Crime Cautionary Tale

Wedged in the back half of the final season of "The Twilight Zone," during an era that saw Rod Serling's classic sci-fi series begin to wind down after five influential years, "I Am the Night — Color Me Black" features a deceptively simple premise. In the half-hour episode, a probably innocent man is due to be hanged, and as locals relish the idea of a public execution, the sun refuses to rise over the town in which he's imprisoned.

The man in question is called Jagger (Terry Becker), and it soon becomes clear that there's more to his case than meets the eye. The self-proclaimed activist, we learn, killed a member of the KKK who had previously participated in bombings and attacked at least one person of color. He also aimed to injure the man who ended up killing him, as a local reporter notes that the dead man "was a cross-burning psychopathic bully who attacked the [convicted] man in there." The crime was self-defense, but the local deputy (George Lindsey), prompted by a "committee of townspeople" who conspicuously decided against an autopsy, lied about the forensic evidence to position it as an unprompted killing.

These truths and more spill out over the course of one dark morning, as the townspeople are moved to honesty by the seemingly judgmental pressure of the endless night around them. Radio announcers note that this place is the only one in the world where the sun didn't rise that day, and as the deadline for the execution approaches, these characters reveal the depths of their inhumanity. The sheriff, it turns out, was up for re-election, while the reporter was driven to sell newspapers and the deputy was fixated on his own public reputation. All of the town's trusted institutions broke down in support of white supremacy –- and the heavens refused to open up as a result.

I Am the Night is unpopular and uncompromising

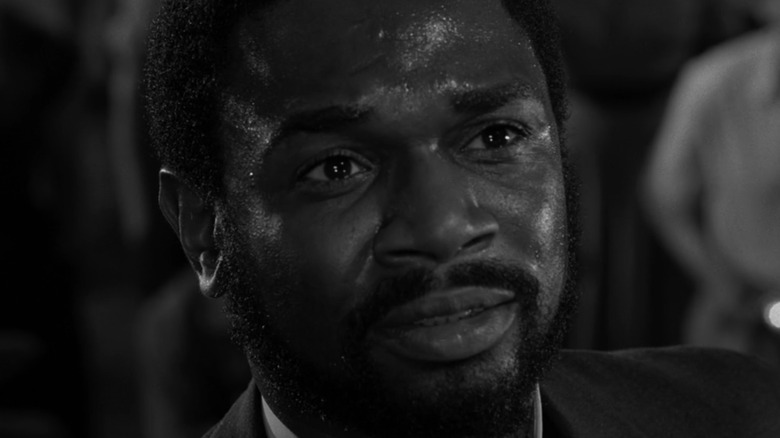

"I Am the Night — Color Me Black" is not a popular episode of "The Twilight Zone." Paste once ranked it 119th in its list of the original 156 episodes, and in the book "The Twilight Zone –- The Complete Episode Guide," author Nick Naughton writes that the cautionary tale "emerges as one of the dullest 'Twilight Zone' episodes in the history of the show." He calls it "slow, talky, [and] dramatically obvious," and notes that it "finds Rod Serling on his high horse to no great effect." To his point, the episode is existential above all else, concerned more with its message than with any semblance of plot momentum. Jagger eventually dies, and the darkness over the city doesn't lift. A reverend (Ivan Dixon) declares that the darkness is hate, so thick in the air they may as well choke on it. "There'll be sun again. There'll be daylight," the deputy insists. There isn't.

While "I Am the Night — Color Me Black" isn't an easy watch, it's one that feels as uncompromising in its sentiments today as it did at the time. It's not just the bigoted man's hate that clogs the air, but the hate of the apparently progressive man who shot him, of the townspeople who showed up for the execution like it was the latest movie, and of the leaders who shepherded this failure of justice. "He hated, and he killed, and now he dies," the reverend says after the execution, addressing the entire town. He continues: "You hated, and you killed, and now there's not one of you who isn't doomed." When this episode aired, 44 states still had a legal right to use the death penalty. As the Civil Rights Movement took the nation by storm, police began getting away with violence and mistreatment that made front page news. And, according to the Tuskegee Institute Archives, Black people were still being lynched in America while "The Twilight Zone" was airing.

True crime fans could learn something from Serling's message

This episode may seem preachy in retrospect, but it brought a comparatively radical message to 20th century audiences at a time when TV was still heavily censored. It's also a message that still resonates today, especially when it comes to the controversial storytelling tradition known as "true crime." At their best, true crime stories can open audiences' eyes to exactly the type of corruption, conspiracy, and institutional racism that "I Am the Night — Color Me Black" spotlights. But when communicated carelessly, true crime stories can also stoke a bloodthirstiness among consumers that's not far off from that of the vicious spectators in Serling's fable.

For every project that interrogates these broken systems (on this front, I personally recommend the podcasts "Admissible: Shreds of Evidence," "Through The Cracks," and "On Our Watch"), there's another that clearly relishes sensationalizing the macabre. Too many true crime narratives still take the word of police and prosecutors as gospel while victim blaming nearly everyone else involved. This is, unfortunately, a medium in which one unwritten rule seems to be that empathy is finite, and it's one that began centuries ago with –- you guessed it –- public executions. Whether it's cable news pundits conflating whiteness and wealth with innocence, TikTok influencers claiming to solve murders with body language analysis, or podcast hosts gleefully relaying the details of a crime scene, it's clear that the air is still clogged with hate and dehumanization today ... and that more people than are willing to admit it are culpable.

Too often, those who gravitate towards true crime do so without considering whether the stories they internalize question the inhuman systems driving our world, or simply reinforce them through myths, stereotypes, and misinformation. The noble cop, the unbiased reporter, the flawless forensic science, the monstrous criminal: "I Am the Night — Color Me Black" breaks down all of these dangerous tropes over the course of just 25 minutes, spreading the blame for one man's execution far and wide. If written today, this episode may well have included Twitter users one-upping each other in a race to wish death upon the subject of the latest Netflix documentary. "Here we are, gentlemen," one character says during what, in a more traditional story, might have been its climax. "treading water in a sewer." Serling's script may be heavy-handed, but it should dig at a sickening truth in the pit of every viewer's stomach.

I Am the Night reminds us that hate is a sickness that spreads among spectators

The episode ends with what could be called a moral twist. It turns out that this unnamed town isn't the only place that's gone dark; a radio announcer reports that Berlin, Birmingham, Vietnam, and other areas around the world have also fallen prey to an all-encompassing darkness. Serling reportedly wrote the episode in response to John F. Kennedy's assassination — Dallas, Texas is included on the newscaster's list of pitch-black places — but the episode also bears some resemblance to a script he wrote for the anthology series "Playhouse 90" years earlier. That hour was originally meant to be about the death of Emmett Till, but Serling's attempts to tackle that horrifying day in then-recent history were gutted by the network (which subsequently sparked his idea for "The Twilight Zone").

A year after "The Twilight Zone" ended, accomplished writer and activist James Baldwin published "Going To Meet The Man," a short story about a virulent racist recalling the day his own father took him to a lynching. This protagonist, too, finds himself engrossed in the violence of public execution. "He felt that his father had carried him through a mighty test, had revealed to him a great secret which would be the key to his life forever," Baldwin wrote. That secret was, as Serling put it during his final words on this episode, "a sickness known as hate." It's a sickness too easily normalized and sublimated, in 1964 and 2024 alike. The show's host and creator was rarely ever more somber than he was when delivering this episode's epilogue. "Not a virus, not a microbe, not a germ," Serling signs off, "but a sickness nonetheless: highly contagious, deadly in its effects. Don't look for it in the Twilight Zone — look for it in a mirror. Look for it before the light goes out altogether."