The Twilight Zone Episode That Inspired One Of Hugh Jackman's Best Films

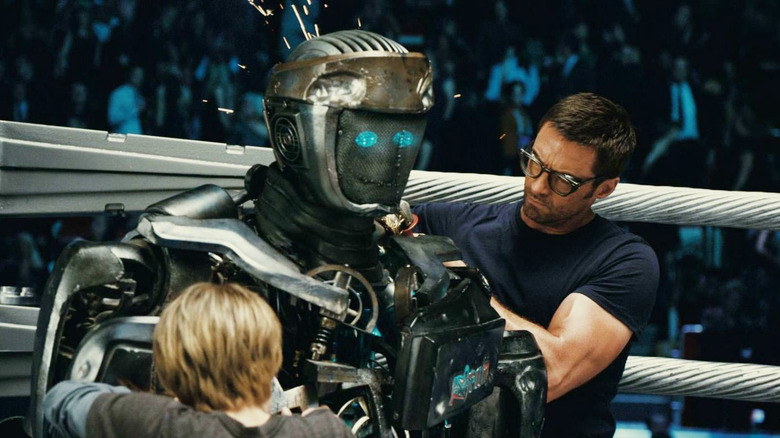

When the big-budget sci-fi/boxing flick hybrid "Real Steel" brawled its way into theaters on October 7, 2011, it was ridiculed by some as "Rock'em Sock'em Robots: The Motion Picture." On one hand, the $110 million-budgeted film's blockbuster pedigree of star Hugh Jackman and director Shawn Levy (and, perhaps most crucially, the marketing) did little to suggest the film was anything more than this. But anyone who grew up gorging on Rod Serling's original run of "The Twilight Zone" in syndication or reading the novels and short stories of Richard Matheson knew there was more to "Real Steel," at least in theory, than family friendly mechanical mayhem.

Obviously, with that budget, Disney (which distributed the DreamWorks production) wasn't going to sell the film primarily on its connection to a nearly 50-year-old black-and-white television show. As for Matheson, while he's considered a god of 20th century sci-fi/fantasy/horror literature by publishing heavyweights like Stephen King and Neil Gaiman, "From the creator of 'I Am Legend' and 'Somewhere in Time'" wasn't going to pack 'em in.

And then there was the "Twilight Zone" episode itself. "Steel," the second episode of the series' fifth and final season, is considered by most fans a middle-of-the-pack effort. Though it's nowhere near as eerie or downright frightening as many of the show's most celebrated tales, "Steel" is built around a nifty twist, one that's become sadly more relevant in our increasingly dehumanized age. And while this twist serves as the narrative hook of "Real Steel," Levy's "Rocky"-fied rendition runs counter to Matheson's cautionary original.

Steel is about a boxer past his prime and out of time

Richard Matheson wrote 16 episodes of "The Twilight Zone," many of which (including "Nightmare at 20,000 Feet," "The Invaders," and "Little Girl Lost) are considered stone cold classics. Like many of his contemporaries, Matheson infused his genre writing with the day's roiling societal issues; he could be brutally skeptical, sharply satirical, or, in the case of "Steel," a touch sentimental.

Matheson adapted his short story for the "Twilight Zone" episode and made very few changes. It tells the tragic tale of Tim "Steel" Kelly (Lee Marvin), an ex-boxer who, six years after the abolition of the sport, manages a robot pugilist along with his mechanic partner Pole (Joe Mantell). Their combatant, Maxo, is an outmoded model that's falling apart after sustaining excess abuse at the hands of devastatingly superior opponents. Kelly is equal parts dreamer and schemer; he believes the scrap-heap-bound Maxo is one good repair away from legging out a few more fights.

Tim Kelly was a flesh-punching man

To properly mend Maxo, however, Kelly and Pole need their fighter to make a semi-respectable showing in a bout against a new model backed by a no-nonsense promoter. When Maxo breaks beyond immediate repair in the locker room, a desperate Kelly disguises himself as a robot and, ignoring Pole's pleas, boxes in his machine's stead. Kelly, who earned his nickname because he was never knocked down during his professional career, gives his nuts-and-bolts opponent all he's got, but he can't phase the machine. Ultimately, he takes a hellacious beating and gets floored before the end of the first round.

The badly injured Kelly instructs Pole to get their share of the purse, but the promoter, citing the first-round knockout, only coughs up half of the money. As Kelly lies bruised and broken, probably dying, Serling delivers a defiant epilogue wherein he views the hero's doomed run as a John-Henry-versus-the-steam-engine moral victory. Per the "Twilight Zone" creator:

"[Humankind's] potential for tenacity and optimism continues, as always, to outfight, outpoint and outlive any and all changes made by his society, for which three cheers and a unanimous decision rendered from the Twilight Zone."

"Real Steel" this is not.

Richard Matheson meets Rocky

Even though he was working from a screenplay by respected A-listers Dan Gilroy ("Nightcrawler") and Jeremy Leven ("The Notebook"), Levy's "Real Steel" looked like a CG-laden, family-skewing programmer à la his "Night at the Museum" blockbusters; ergo, for admirers of Matheson and fans of "The Twilight Zone," it looked eminently skippable. But while the shape of the narrative is more of a "Paper Moon"/"The Champ" mash-up, the heart of Matheson's story is nestled within the studio-pleasing machinery.

Jackman's Charlie Kenton is, like Marvin's Kelly, an ex-boxer working the fringes of the robot-fighting circuit with substandard combatants. But since this is a four-quadrant flick, Charlie must have considerably more skin in the game, namely his son Max (Dakota Goyo), whose mother has only just died and whom he hasn't seen since birth. When they discover a scrapped robot named Atom with a built-in "shadow function," which allows Charlie to imbue it with his boxing smarts, they unwittingly find themselves managing a formidable underdog.

Thanks to off-the-charts chemistry between Jackman and Evangeline Lily, top-tier visual f/x and a rousing sports-film story arc told with unabashed conviction, "Real Steel" is a smashingly entertaining winner (it remains the only good movie Levy has directed). I've no idea why it wasn't a hit theatrically (a $300 million worldwide gross on a $110 million budget is sub-optimal), but it's since caught on via streaming. I gladly recommend it to parents looking for something they can watch with their kids without wincing, and would happily sit through another viewing right now. It's wildly re-watchable.

Alas, its rejiggering of Matheson's central conceit hasn't aged well. In fact, "Real Steel" now plays a bit like a betrayal of its source material.

Real Steel plays problematic in the age of AI proliferation

Kelly is not a noble working man like John Henry. He accepted the prohibition on his sport (enacted due to its barbarity, something that seemed possible in the early 1960s but unthinkable today given that bare-knuckle boxing is making a comeback), and violently bullies Pole into sticking with their futile management of Maxo. When he opts to step in the ring himself, we see it as an act of tragic desperation. It's only afterward that his damn-the-torpedoes sacrifice takes on a virtuous quality.

In "Real Steel," Kelly's redeems himself in part by pouring every ounce of his boxing know-how into Atom's CPU. In turn, Atom becomes a wiser, more lethal and simply more capable fighter than Charlie ever was. Nowadays, the notion of a human being teaching a machine to replace him (even though that replacement has already happened in this case) isn't quite so uplifting. While this wasn't on many people's minds back then, there's connective tissue between Charlie's actions and programmers uploading the works of great writers to ChatGPT and so on.

Most great sci-fi writers are both fascinated and terrified by science. They're as knocked out by each new technological advancement as we are, but they immediately think ahead to its misapplication. And when it comes to automatization, they see a dystopia overrun by irrelevant, unemployable wretches.

Regardless of his animating motive, Kelly fights to what is likely his last breath to resist the dehumanization of industry, sport, and life in general. Meanwhile, Charlie and Max learn to love the machine. One day, sooner than they think, they'll regret their complicity.