The Boys Creator's Best Comic Is The One Least Like His Others

Garth Ennis, the writer behind "The Boys" and "Preacher," has been called the Quentin Tarantino of comic books. On the surface, both men tell stories filled with violence, profane dialogue, crass comedy, and their fans love them for it. I've adored Tarantino since I first encountered him — no movie, from "Reservoir Dogs" to his latest (and favorite of his own films) "Once Upon A Time In Hollywood," has broken that spell. My feelings on Ennis are more of a journey; I dismissed him in my younger days but I've since settled on the more positive side.

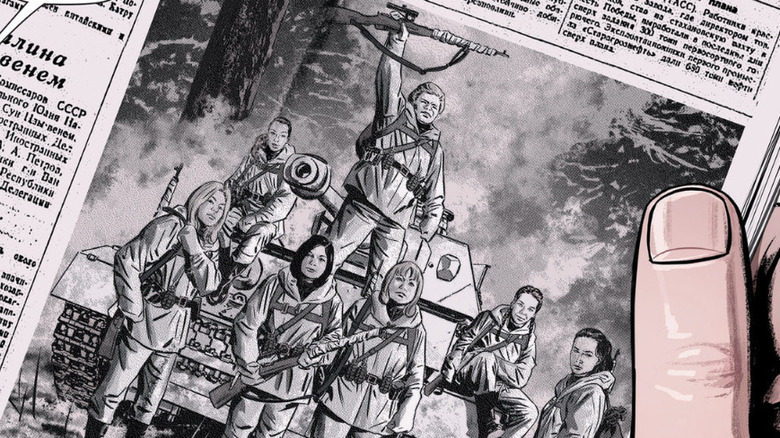

The comic that got me to give Ennis a second look is his 2018 war mini-series, "Sara" (drawn by Steve Epting and colored by Elizabeth Breitweiser). Ennis grew up reading war comics and now he writes them quite well.

Published by TKO Studios, "Sara" is set in Russia during World War II (or as the Russians call it, The Great Patriotic War). It follows the eponymous woman, a Red Army sniper in an all-female squad fighting in the Siege of Leningrad. Broken into six chapters, each issue of "Sara" has two parallel timelines; an issue-to-issue continuing story of Sara fighting in winter 1942 alongside her sisters-in-arms, and then flashbacks that each shed light on one piece of her backstory. (e.g. Chapter 2 — "Theory & Application" — shows Sara's field training as a sniper.)

"Sara" has a premise that could easily be a novel or a film instead of a comic; the 150 pages after the cover follow through on that. (I'm not saying "Sara" doesn't do anything well with its chosen form; more on that later.) This is what drew me to it; it seemed like such a straightforward story and one that couldn't possibly have Ennis' usual excesses or gross-out humor. Indeed, "Sara" proves what wonders Ennis can do when he restrains himself.

My evolving relationship with Garth Ennis and his comics

A key piece of Garth Ennis' reputation is that he's the comic writer who hates superheroes. Since we Americans often think of "superhero" and "comic book" as synonymous, this seeming contradiction stands out. Ennis is not Alan Moore, who loved superheroes as a child but became disillusioned with them, either; he never read cape comics as a kid and so, when introduced to them as a teen, only saw them as ridiculous. Why else would he write a comic like "The Boys," an exercise in subjecting superheroes to his trademark creative and vulgar death scenes?

Now, I first heard of Ennis when I was a preteen superhero dork. Before I'd even bothered to read his comics, I was turned off. Reading that the one superhero he likes is the Punisher "confirmed" for me the perception I'd built up of him as an edgelord who just likes blood and guts, being too cynical to write anything else. Well, I was wrong and short-sighted. (Garth, if you're somehow reading this, mea culpa and apologies.) Part of my transformation was just listening to Ennis speak in interviews; the soft-spoken Irishman I found had none of the immaturity or venom I'd imagined.

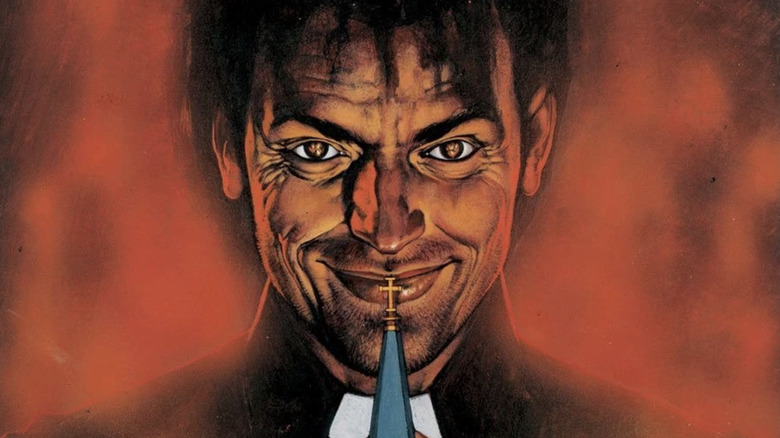

I've also since actually read more of Ennis' work (which, again, I should've done in the first place). "Preacher" is a masterwork that finally won me over to the beauty of the late Steve Dillon's art. I've still never been able to quite enjoy "The Boys" comic, but I appreciate it as some needed counterprogramming to the superhero Big Two, especially since I have been able to enjoy "The Boys" TV show.

Preacher, Garth Ennis' messy masterpiece

Ennis' writing is much more meaningful than I'd imagined too. This is where he again intersects with Tarantino; some dismiss them as reactionaries because their dialogue isn't PC, but pay closer attention and you'll notice the righteous rage animating them. The violence in their stories is often inflicted on evil that deserves it. Just as Tarantino uses his canvas to invent punishment for Nazis and antebellum American slavers, Ennis does the same to Christian fanatics and corporate America.

I still don't unreservedly love Ennis' sense of humor, though; he often takes his crass and sadistic tendencies too far for me. "Preacher" has wonderful writing about romance, the American immigrant experience, and the unfairness of a "loving God" making a world where his children suffer. It also has Nazi dominatrices, in-bred descendants of Jesus Christ, porn star manslaughter via a charged vibrator dropped in a jacuzzi, and well, Arseface. Reading "Preacher" from beginning to end, one feels Ennis gradually growing more comfortable as he pushes the envelope, so he does it more and more.

Sometimes, Ennis' sincere and indulgent sides mix well. In "Preacher" #45, our hero Jesse Custer pisses on a burning cross left by the KKK. In issue #54 (the most romantic of the whole series), a drunk spews out, "When you can jerk off to the thought of your wife and not just some blonde in a stroke book? That's when you know it's love."

Other times, though, it can be exhausting. (/Film's review of "The Boys" season 1 from 2019 said as much.) Not in "Sara," though, which has all the pathos and none of the obscenity.

Sara is a war comic for the ages

There's a lot of World War II historical fiction there, but "Sara" gives a perspective that isn't quite so well-tread: the Soviets'. They were just as vital in defeating Nazi Germany as the other Allies. When Americans think of World War II battlefields, we think of Omaha beach on D-Day (especially thanks to "Saving Private Ryan") and bombed-out German cities. "Sara" takes place in snow-blanketed forests; Chapter 1 — "Words To Live By" — opens with Sara perched on a treetop waiting for her perfect shot. The conflict is familiar but the battlefield feels new.

Epting and Breitweiser aim for realism, both in the line art and the coloring. Since most of the comic's palette is bluish-white (both the snow and the soldiers' colored-for-camouflage uniforms), the red blood splatters pop all the more.

The art is what ultimately compelled me to read "Sara," since I'm not often the biggest fan of how Ennis' comics look. Dillon's art is an acquired taste and I'm still not in love with Darick Robertson's work on "The Boys." Epting, though, was the primary artist on Ed Brubaker's "Captain America," one of the first comic runs I collected; he's an artist whose involvement in a book will always pique my interest.

"Winter Soldier," Brubaker and Epting's kick-off arc on "Captain America," features a sequence of Cap and Bucky fighting on the Russian front during World War II. Back then, Epting ceded art duties to Michael Lark (presumably to make the flashbacks stand out against the present-day scenes that he did draw), but on "Sara," he finally gets the chance to draw Russia at war and all of their winter soldiers.

Ennis hates Captain America ("The Boys" viciously lampoons him with Soldier Boy), but clearly even he recognizes Epting's talent.

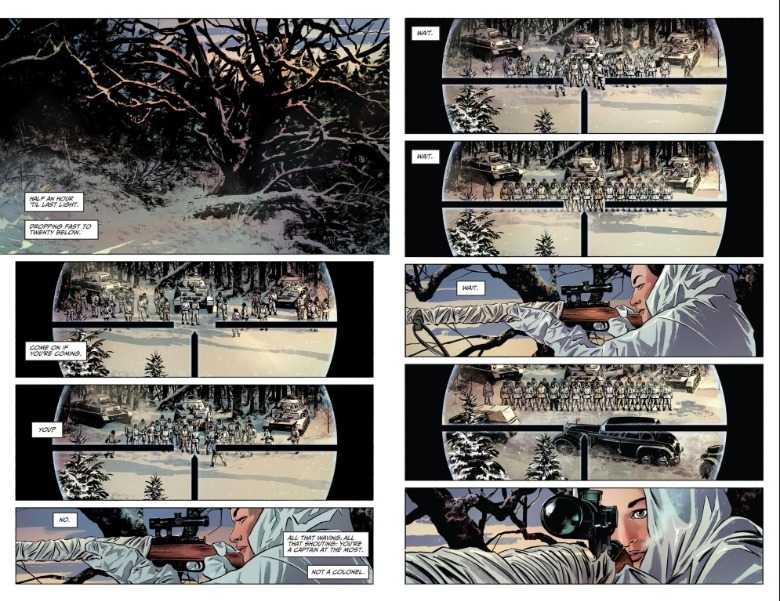

Sara shows World War II through a sniper's lens

The art is also how "Sara" proves this story of a sniper is best told as a comic book. Being a sniper means a lot of time sitting still and waiting with only your thoughts for company; "Sara" puts its reader in her head with text without sacrificing the rhythm that a visual medium offers. Epting lays out his panels like a movie editor cuts footage; wide shots of the targets in Sara's sights, then cut to a close-up of her aiming, repeat. Sometimes he'll reuse near-identical panels twice in a row, not to save himself effort but to underscore how Sara is patiently staying still even as the world passes around her.

Across these panels, Sara narrates the scene and what she's thinking in text boxes. Since you read her thoughts in your own voice, it feels more intimate than either the silence or narration that a movie could offer. Compare David Fincher's "The Killer," which opens on a prolonged sequence of its assassin lead (Michael Fassbender) preparing a sniper shot. Fincher invites you into the Killer's head, but the voiceover is external to the viewer; it can't grab you in quite the same way as a medium that uses both visuals and unspoken text.

How Sara compares to other Garth Ennis comics

"Sara" is Garth Ennis at his most mature. I imagine it would've been tempting to show the decadence of the USSR leadership with an orgy or two, but he holds off his expected excess and it makes "Sara" sing. The story is as stark as its winter setting — but not so cold, for Sara (both the story and the character) honors the humanity of the women fighting alongside her.

If there's anything "Sara" shares with its writer's past work, it's an outlook that war is the act of institutions shoving their citizens into the meat grinder. In Ennis' war comics, he manages to tell this theme while also avoiding sanctifying his soldier characters. Ennis' soldiers aren't pure heroes failed by an undeserving state, just normal blokes who've been fed lies about their country's greatness. Once in combat, they reap the consequences while under fire.

The Red Army's refrain is "For The Motherland." In Chapter 5 — "Recognition & Reward" — Sara eyes two of her squadmates being killed by German soldiers and observes "I can't hear the words. But I know them all the same." Sara, though, doesn't believe in those three words; she's fighting the Nazis because she was told that they razed her village. Her faith in her government is fragile at best (feelings not alleviated by her worrywart political overseer Raisa). She confesses to her friends in Chapter 6 — "Against A Ghost" — that she believes Russia is content to "drown the Fritzies in our own blood." No war is truly "great and patriotic," but while dying for an ideology or uncaring state is foolish, dying for your comrades can be noble.

Ennis and Epting are currently working on a spiritual sequel to "Sara" titled "Partisan," following a Ukrainian mother caught between the warring Germans and Russians in 1942. I have every faith the pair can again strike a clean shot.