The Best Comics Fans Of The Boys Should Read

It's a tragedy that "comic book" is synonymous with "superhero." If film is sometimes dismissed as a less mature medium than literature, and television in turn deemed less than film, then comics are at the bottom of that rung. The medium being the birthplace of an inherently childish genre about strongmen in capes doesn't dissuade the uninitiated of that notion.

Someone who definitely agrees with me is Irish comic writer Garth Ennis. He co-created "The Boys," a series where CIA agent Billy Butcher leads a five-man squad dedicated to taking down corrupt "supes."

Ennis grew up reading war comics and the magazine "2000 AD" (home of Judge Dredd), so he has no childhood fondness for superheroes and can look at them with a different eye than most comic writers. "I don't hate superheroes," Ennis has protested. "I just think they're kind of silly." Hence, "The Boys" is all about taking the piss out of superheroes, from the corporate media hegemonies that pump out their stories to the idea that these crimebusters are "heroes" at all.

"The Boys," co-created by artist Darick Robertson, ran for 72 serialized issues from 2006 to 2012. The Prime Video TV adaptation of "The Boys" (created by Eric Kripke) is now entering its fourth season.

That show has redeemed "The Boys" to me. I've never been a huge fan of the comic, a series of awful people doing awful things amid a truckload of gore and vile humor. The show is also that, but with wit and heart. (I'm also not a fan of Robertson's art, but that's a me thing). Full disclosure: I did grow up on superheroes, so I can't spit the same venom at them that Ennis does, but I agree with him the genre is not above reproach.

If you like "The Boys" (comic or show), here are some more titles you should read.

Marshal Law by Pat Mills and Kevin O'Neill

"Vigilantes taking down corrupt superheroes" is such a unique pitch. Where did Ennis get it? From Pat Mills and Kevin O'Neill's "Marshal Law," a British comic that Ennis openly cites as an inspiration for "The Boys."

Marshal Law, aka Joe Gilmore, is a futuristic police officer in "San Futuro." Law's world is one where superheroes are commonplace, and like in "The Boys," their sterling reputations are just good PR; at best they're dangerously unpredictable, at worst they're deviants. So, Marshal Law is responsible for policing them, which he does with both genetically engineered strength and lots of guns. (He's basically Judge Dredd if he fought superheroes.) As Law puts it, "I hunt heroes. Haven't found any yet."

Pat Mills, co-creator of "2000 AD" and "Judge Dredd" with it, was Garth Ennis before Garth Ennis. Ennis mocks superheroes, but Mills straight-up despises them as fascists. Each subsequent "Marshal Law" story is about him fighting a parody of a popular superhero/superhero team; he's sure to verbally take them apart before doing so physically. Some comic artists neglect their backgrounds, but not Kevin O'Neill. Each panel of "Marshal Law" is packed with detail, from collage-style coloring to diegetic graffiti. He draws his superheroes with the same outrageous and colorful costumes as the real deal but makes them look grotesque, not inspiring.

Law himself is not spared from Mills' and O'Neill's savagery of superheroes ("Marshal Law" itself is a punny name right out of DC or Marvel); the comic hates him almost as much as his targets. "Kingdom of the Blind" ends with the saying of how in such a land, "the one-eyed man is King." Law is that one-eyed man.

"Marshal Law: The Deluxe Edition," collecting the essential stories, is available for digital purchase.

Miracleman by Alan Moore, Garry Leach, Alan Davis, Chuck Austen, Rick Veitch, John Totleben, and John Ridgeway

"Watchmen" by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons is the canonical comic. The one superhero "graphic novel" (Moore hates that term) that non-comic readers feel comfortable praising as great writing. That it was the first superhero deconstruction to get mainstream attention (without being bound to iconography like Frank Miller's fellow 1986 release, "The Dark Knight Returns," ultimately was) helped. Comic fans embraced the idea that superhero stories could be "mature" and have been pushing for "Watchmen" style reverence for their favorite funny books since.

Ennis cites "Watchmen" as an inspiration for "The Boys" alongside "Marshal Law." If "Marshal Law" is the work of someone who never liked superheroes, "Watchmen" is by someone who did once but grew up and realized they're silly.

I'm going to recommend something a bit more obscure, though (outside comic circles at least); Moore's first superhero epic, "Marvelman." The series, now called "Miracleman" thanks to copyright issues, was drawn by a succession of artists and revived a UK-exclusive riff on Fawcett Comics' "Captain Marvel." Those comics were canceled after DC sued Fawcett, claiming Captain Marvel was a knock-off of Superman, so English writer Mick Anglo started penning "Marvelman," a thinly-veiled "Captain Marvel" continuation.

Moore's "Miracleman" focuses on middling journalist Mike Moran, who grew up and forgot his childhood adventures as Miracleman — until, one day, he remembers the magic word "Kitoma!" that gave him powers. Like in "Watchmen," Moore shows that if superheroes really existed, then them changing the world would be terrifying. The gore of "The Boys," which is so often about exploring the dark potential of superpowers, doesn't exist in a world without "Miracleman" #15's climatic battle that levels London.

Moore's "Miracleman" is collected in both three volumes ("A Dream of Flying," "The Red King Syndrome," and "Olympus") and an omnibus edition.

The Ultimates Volumes 1 and 2 by Mark Millar and Bryan Hitch

Mark Millar and Bryan Hitch's "The Ultimates" relaunched "The Avengers" for the 2000s as part of Marvel Comics' "Ultimate Marvel," a reboot that ran alongside the original rather than erasing it. "The Ultimates" was the primary inspiration for 2012's "The Avengers" (director Joss Whedon wrote a glowing introduction to "Ultimates" Volume 1 in 2004). The Marvel Cinematic Universe is a primary target of "The Boys," so why should fans of the latter read source material of the former?

Millar's resume also includes "Kick-Ass" and "Wanted" — he brings that same edgelord mindset to "The Ultimates." Ultimate Captain America is Soldier Boy before Soldier Boy, Ultimate Iron Man has utterly surrendered to the demon in a bottle, Bruce Banner's girlfriend Betty Ross is a cynical PR flack akin to Ashley Barrett (Colby Minifie), and the SHIELD characters (Nick Fury, Black Widow, and Hawkeye) are all soulless spooks. Yes, the comic that inspired "The Avengers" is really more like "The Boys."

I have a complicated history with "The Ultimates." I first read it in 2013 or so, deep in my high school era MCU fandom. Unable to look past surface text and see anything but my favorite toys behaving more like tools, I dismissed it as "The Avengers" directed by Michael Bay. As my political conscience grew, however, I found myself developing more of a soft spot for it, particularly Volume 2. (Hitch's spectacular art, which is cinematic down to aping movie stars' looks for its characters, helps too.)

In "The Ultimates," Earth's Mightiest Heroes weren't assembled to save the world, but to topple foes of the American Empire. The "villains" of Volume 2 are the Liberators, an international coalition of superhumans assembled to invade America. Millar ultimately pulls his punches, but I can't help but admire him for at least reaching for ruthless satire while Bush was still in office.

"The Ultimates" is available on digital reading service Marvel Unlimited, as well as in several collected print editions.

Irredeemable by Mark Waid, Peter Krause, and Diego Barreto

Mark Waid is probably the biggest Superman fan on planet Earth. (Read here for his opinion on 2013's "Man of Steel," itself inspired by his and Leinil Francis Yu's "Superman: Birthright.") That makes him an unexpected but perfect choice to take apart his icon with the 2009 comic "Irredeemable." Stories of "evil Superman" are a dime-a-dozen, but this 37-issue series is the best take on it you're going to get.

The Plutonian (as in P.L.U.T.O — Piety, Loyalty, Utility, Truthfulness, Order) is Earth's greatest and most humble hero. That is, until he snaps one day, kills several of his colleagues, and decides he'll be Earth's greatest villain instead. "Irredeemable" #1 opens with the Plutonian's rampage; as the comic looks back to find where things went wrong, Waid admirably doesn't invent a dramatic reason for the Plutonian's heel turn.

The Plutonian's kind personality wasn't fake per se, but he was playing the part of an ideal hero because he wanted love and admiration. Instead, he got a populace that was utterly dependent on him; the straw that broke this camel's back was a rich a-hole complaining the Plutonian damaged his boat instead of being grateful he was rescued. So, the Plutonian decided to live for himself — which meant silencing all the begging voices of the world instead of answering their calls.

Homelander (Antony Starr) of "The Boys" also fits the "Superman gone bad" archetype. The show sometimes posits that if "John" had been raised with a family, not a lab, he'd have been a better person. "Irredeemable" explores this counterfactual; the Plutonian bounced from foster home to foster home because his powers terrified all his guardians.

Even while writing "Irredeemable," Waid clearly believes in the idea of Superman — so (without getting specific) the Plutonian's defeat is performed in a way to inspire someone better from his foundation.

"Irredeemable" is available both digitally and in print via 10 volumes, five "Premier Editions," and an omnibus.

Black Summer by Warren Ellis and Juan Jose Ryp

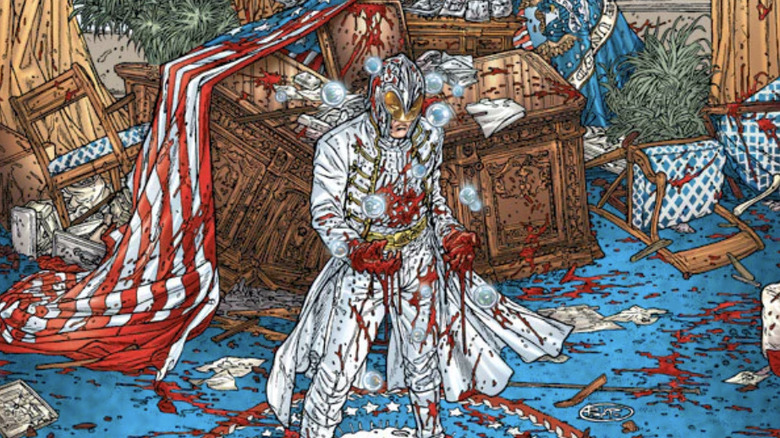

"Black Summer" cuts between two scenes in its open pages. In the first, retired superhero Tom Noir stares in his bathroom mirror, lamenting his age. Pretty ordinary stuff, until he switches on CNN and sees the other half of this opening. Noir's old comrade, John Horus, marches onto the White House's press briefing room, covered in blood and announcing that he's killed the president, vice president, and their cabinet.

Ellis and Ryp published "Black Summer" in 2007. Like any member of the U.S. public with a brain or soul did by that year, Horus has realized that the 2003 invasion of Iraq was illegal and started under false pretenses. So, he cut the head off this snake and has declared he will oversee a new election to make the right people get into office this time.

"Superman assassinates the George W. Bush administration" is one of the most jaw-dropping premises for a comic I've ever heard. It's all the more fascinating because Horus has not turned evil like the Plutonian or Homelander. No, he still believes he's the world's greatest hero and that his job is to fight evil in all its forms. The contradiction between the leaders of America, the country whose dream he defended, doing something utterly heinous broke him. In any other case, he wouldn't hesitate to take down a war criminal, so why should that war criminal being the president make him act differently?

If you're a Liberal, there can be some dark catharsis to this opening. Ellis, though, presents Horus not as a savior but just a superpowered Lee Harvey Oswald. The rest of "Black Summer" is not about him remaking the world like Miracleman did, but federal authorities hunting down Horus, Noir, and their other teammates in the "Seven Guns."

In Warren Ellis comics, superheroes are never the solution to a problem the people must fix.

"Black Summer" is available as a single print collected edition.

Incognito by Ed Brubaker and Sean Phillips

Ed Brubaker's one of the brightest voices writing in American comics. His primary calling is crime comics; he and artist partner Sean Phillips usually put out at least two new noir books a year. Brubaker also wrote a fair bit of superhero comics in the 2000s (he co-created the Winter Soldier while writing "Captain America"), but these days, he sticks only with crime fiction (his and Phillips' "Criminal" anthology series is getting a TV show on Prime Video, streaming alongside "The Boys").

If any of you "Boys" fans want to brush up on Brubaker before "Criminal" airs, the work you'll probably like the most is "Incognito," which centers on former supervillain Zack Overkill living in witness protection. Zack, forced into the middling life of an office drone, is like Henry Hill (played by Ray Liotta in "Goodfellas") if he was a pulp villain and not a mafioso.

"Incognito" is the best melding of Brubaker's noir and superhero work (aside from "Gotham Central," but that was more so Greg Rucka's baby). As Brubaker writes in the comic's back pages, "Both superhero comics and crime comics grew out of the pulps, so why not smash them together?"

Phillips' character and background drawings hew towards realism (he's unmatched at drawing realistic stubble and lips), but he lets colorist Val Staples shade each panel with a primary filter; one might be purple, then the next red or yellow. He, in turn, divides most of his pages with three horizontal lines, but doesn't always confine himself to a nine-panel grid; frames are as thin or wide as they should be without rigid structure.

This flow of mood and framing makes Brubaker and Phillips' books feel cinematic, as overused as that term is in comics. "Incognito" is no exception.

"Incognito" consists of two volumes: the six-issue original and a five-issue sequel subtitled "Bad Influences." The volumes are available separately and as a collected "Declassified Edition."