Videodrome's James Woods Filmed Part Of The Horror Movie Without Telling His Agent

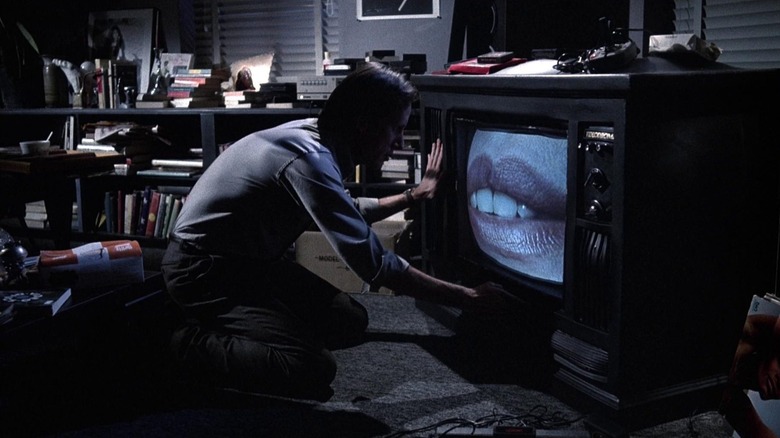

David Cronenberg's "Videodrome" was made in the wired world of 1983, when cathode ray tubes were the only video screens available, Betamax videocassettes were still common, and snagging pirated TV signals with special antenna equipment was still seen as a punkish subversion of dominant media paradigms. The technology may be dated to audiences in 2024, but Cronenberg's sci-fi essay on media obsession remains as timely as ever, easily applicable to a screen-addicted generation accustomed to a state of near-constant media consumption. When we're constantly projecting ourselves into virtual spaces, are we essentially inventing new bodies for ourselves? New Flesh?

James Woods plays Max, a media pirate who has recently discovered a mysterious rogue TV signal — Videodrome — that carries a 24-hour show of nothing but scenes of torture. Max, jaded by violent media, finds it fascinating and thinks he can broadcast the signal on his local public access station, free of censure. Max is already notorious in the local media world, and he is regularly invited onto high-end talk shows to discuss media literacy and the changing state of television. On one of the talk shows, he meets Nicki Brand (Debbie Harry), an S&M-positive radio host, and the two begin an affair. Max's interactions with Nicki, however, come to reveal a strange underground media conspiracy and the revelation that Videodrome may possess eerie subliminal messages that cause hallucinations and leave the viewer susceptible to suggestion.

"Videodrome" is a techno-thriller with Marshall McLuhan underpinnings. It's one of the best films of the 1980s.

In a 2014 interview with Den of Geek, Woods talked about making "Videodrome," and how Cronenberg's script didn't have a satisfying ending. When it came time to do some reshoots, Woods merely met with Cronenberg to finish the film, all without telling his agent.

Long live the new ending

Woods said Cronenberg had written multiple endings for "Videodrome," and was still unsure as to how the film should end, even during production. The 1997 Faber & Faber book "Cronenberg on Cronenberg" reveals an ending wherein Max, Nicki, and Brian O'Blivion's daughter Bianca (Sonja Smits) appear inside the Videodrome set, sprout new sets of genitals from their midsections, and have an orgy with them. That ending wasn't clicking, though, and Woods talked about the new ending, saying:

"I loved working with David and so on, and it was a prescient movie as it turned out, but at the time he offered me that movie, we only had 70 pages of the script! I literally called David up and said 'what do you think of the ending?' and he said 'I'm not crazy about it.' I said 'I've got some ideas,' and he said 'come on up, we'll shoot some more.' So I flew up to Toronto to shoot another ending. We shot three endings. I didn't even tell my agent!"

The final ending of "Videodrome" was pretty bleak. Warning: spoilers follow.

Max had been employed by a shadowy organization to commit strange, supernatural assassinations, and a gun had become organically fused with his hand. After committing his murders, Max fled to a derelict ship wherein a TV sits glowing. Nicki appears on the screen and tells him to shed his old flesh and praise the New Flesh. This requires the taking of his own life. Which he does. Woods said:

"I think the final ending of 'Videodrome' was my idea, that it was a self-fulfilling prophecy that he'd just explode, or implode essentially. And he said 'yeah, I think that's what we're trying to say.'"

Cronenberg found the ending organically with his actor.

James Woods' mom didn't like Videodrome

Cronenberg can be cagey about certain reads of his films, often shutting down interviewers who want to offer interpretations. In some cases, he will say outright what his films are meant to be — Cronenberg has spoken eloquently about how "The Fly" is an interpretation of watching a loved one slowly die of disease — but in other cases, he will merely say that the audience already sees everything he wanted them to; he hasn't offered any "meaning" behind "Crimes of the Future."

It seems that Cronenberg didn't quite have a mission statement with "Videodrome" other than the general themes of media obsession and susceptibility to violence. When Woods came up with the ending, it was enough for the director, and he called it a day. Woods, however, recalled talking to his mother, and that his mother sensed Cronenberg's lack of focus. The actor said:

"[Cronenberg] wasn't really sure what the story was, and I think my mom sensed that in a way. She said 'look, I get all this video stuff, Marshall McLuhan and all that. But the story just doesn't captivate you, you don't care about that character.'"

And, to be fair, Cronenberg is a notoriously cold director; his tales aren't often about affection, warmth, or togetherness. "Videodrome" wasn't a big hit for Universal which tried to sell it as a nationwide release. It was too weird for a mainstream audience, but too violent for the art houses. It ended up falling through the cracks. These days, one can see it in pristine condition via the Criterion Collection. Although watching it on Betamax might be more appropriate.