Four Fantastic Doctor Doom Comics Marvel Fans Should Read

Doctor Victor Von Doom is the greatest supervillain Marvel has. Not just because of his rocking green cloak and metal armor look (an outfit so cool, "Star Wars" ripped it off), either, but because of his persona. Doom is a man so grandly arrogant he thinks the world can only be saved if he rules it, yet so petty he lets a misplaced grudge against Reed Richards rule him.

Doom's vanity is so supreme he hides his scarred face behind a mask; not because he fears the judgment of others, but because he can't bear to see an imperfection when he gazes in the mirror. And yet, when he makes his grandiloquent declarations (always in the third person), it's not empty pomposity. Statements like "Doctor Doom does not fail!" delivered free of irony could be laughable, but instead Doom's willful personality convinces you.

Doom has been the villain of countless Marvel books; he famously doesn't limit himself to sparring with only his chief nemeses, the Fantastic Four. He was the villain of "Secret Wars"; both the original 1984 one and the 2015 multiverse-ending event that homaged it title. 1987 one-shot "Emperor Doom" sees him finally seize the world and ask the question every dog does once it catches a car. One of my favorite Doom tales is "Unthinkable" (from Mark Waid and Mike Wieringo's "Fantastic Four"), where Doom proves he'll sink lower than Hell if it means humiliating Richards.

Yet, Doom is such a commanding presence, and has enough pathos to rival the heroes he fights, that many writers have used him as a protagonist. These are the comics we'll be focusing on.

All listed comics can be read on digital reading service Marvel Unlimited.

Books of Doom by Ed Brubaker and Pablo Raimondi

Doom's backstory was first told by his creators, Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, in "Fantastic Four Annual" #2. Victor Von Doom was born into a nomadic Roma tribe in the European nation Latveria. His mother Cynthia, a witch, and his father Werner, a doctor, both met early graves thanks to Latveria's ruling Baron. A young Victor mastered both his parents' vocations and went to school in America. An experiment to contact his mother in the "nether realm" blew up in his face, so he then sought out an order of monks in the Himalayas who helped forge his armor.

What Lee and Kirby confined to 12 pages, Brubaker and Raimondi expanded to 120. "Books of Doom" honors Lee/Kirby — Brubaker even uses some of Lee's dialogue, such as Doom declaring "Pain?? That is for lesser men!" when he adopts his mask — but it fleshes out their original montage into a story.

Issue #3 shows Doom living in Prague for a time with his childhood love Valeria, in between his days in America and then the Himalayas (in the original telling, Doom gets his scars and then armor on the same page). In "Fantastic Four Annual" #2, this origin story ends with Doom flying off back to Latveria; the next panel is a collage of newspapers about his supervillain schemes. Brubaker uses "Books of Doom" issues #5 and #6 to show how Doom seized control of Latveria, leading a people's revolution against the Baron and avenging his family.

The book's framing device is that Doom himself is recounting his early days; the resulting need for narration allows Brubaker plenty of room to write in Doom's flowery voice. Though called "The Books of Doom," the comic intersplices other "interviews" with Doom's acquaintances to show his own self-possessed views are often inaccurate ones.

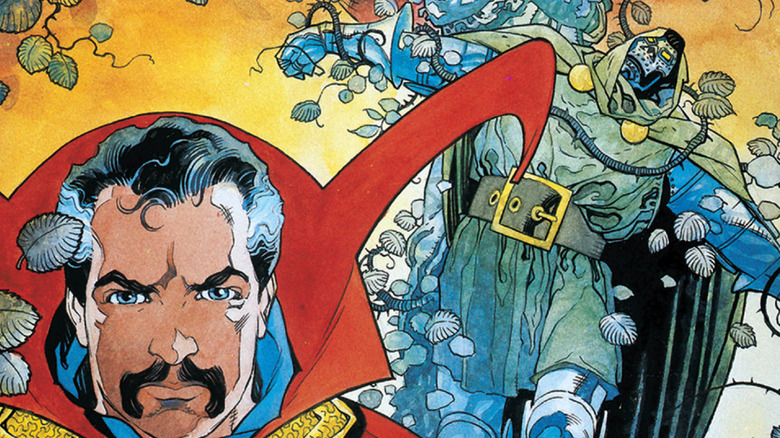

Doctor Strange and Doctor Doom: Triumph and Torment by Roger Stern and Mike Mignola

As a practitioner of black magic, Cynthia Von Doom's soul was damned to Hell when she died. "...Though Some Call It Magic!", a back-up story published in 1971's "Astonishing Tales" #8 (written by Gerry Conway, drawn by Gene Colan), establishes that Doom engages in an annual battle with the forces of Hell to free his mother's soul. His efforts are always, well, doomed — until 1989's Marvel Graphic Novel #49: "Doctor Strange and Doctor Doom: Triumph and Torment."

Elder god trio the Vishanti summon the great sorcerers of Earth, pitting them against each other to name the Sorcerer Supreme. The winner is Doctor Stephen Strange, but Victor Von Doom is the runner-up. Per contest rules, Strange must grant Doom a "boon" of his asking; Doom's request is that Strange help him free Cynthia's soul. Side-by-side, the two plunge into Hell.

This epic is penned by Roger Stern, but the star is penciller Mike Mignola, the future creator of "Hellboy" — his depiction of Hell and all its demonic denizens in the book's third act feel like a trial run for it. "Triumph and Torment" boasts the heavy shadows and sharp line work now synonymous with Mignola's style.

Inker Mark Badger uses watercolor, rather than the thicker colors of later "Hellboy" art, making the demonic art more ethereal. Badger colors the hellfire with a golden hue, heightening the contrast with the scarlet red of Mephisto's own cape.

The result looks halfway between Mignola and the classic Doctor Strange art by the character's creator, Steve Ditko. The story's fidelity to the classics doesn't stop there; Mignola also recreates certain panels of Doom's origin in "Fantastic Four Annual" #2. Badger simply but effectively shades these flashbacks in greyscale.

The remarkable ending of Doctor Strange and Doctor Doom: Triumph and Torment

Spoilers follow.

The art of "Triumph and Torment" makes it a unique animal among the sea of Marvel Comics, but the writing is far from poor. The book's resolution is Stern's coup de grace.

Doom seemingly betrays Strange, trading the Sorcerer Supreme's soul for his mother's. Cynthia, when she learns of her son's infernal deal, refuses to leave Hell and disowns Victor. This very act redeems her and she ascends to Heaven, leaving Mephisto with nothing. As Strange surmises, this was Doom's plan all along; Victor ends the book triumphant yet tormented by the last words he shared with his mother.

So, Doom was willing to make his beloved mother hate him if it meant she could rest in paradise. But was this because his love for her was that overpowering? Or was it because he cared even more about winning through his own guile? No matter, because the result was the same. Long-running Marvel characters are often saddled with goals they can't complete because doing so would conclude their stories. The X-Men still struggle for mutant equality while Bruce Banner has not found equilibrium with himself and the Hulk, but Doom did free his mother.

Clever enough to trick the Devil himself and resolved enough to overpower the "illusion of change" that runs superhero comics. That's the might of Doom, baby.

Doom #1 by Jonathan Hickman and Sanford Greene

Writer Jonathan Hickman's ascension as Marvel's superstar writer has been a journey he's shared with Doom. Hickman entered the A-leagues writing "Fantastic Four" and his "Avengers" epic, capped off by the 2015 "Secret Wars," gradually revealed Doom as its center. One of Hickman's latest works is the 48-page one-shot "Doom" issue #1. Despite Hickman's affinity for the Doctor, the story is the pet project of artist Sanford Greene; Hickman just helped him realize it (tellingly, they're credited collectively as providing the "Art — Plot — Script").

"Doom" #1, titled "Days of Doom," shows what happens when Doom is the universe's last hope. The comic is set in a possible future where Galactus has wiped out Earth and all its champions. Valeria Richards, daughter of Reed and honorary niece of Doom, revives her uncle to stop Galactus' final plan: destroying and remaking the universe.

As the mastermind behind the comic, Greene's command of his pencils is absolute. Almost no page uses a traditional, orderly panel layout (instead, smaller panels are mostly layered on top of larger drawings). Many panels are not even rectangles or squares at all; when Doom faces off with Galactus' heralds, the pages are divided by uneven diagonal borders, like the structure of the comic is swaying and flowing with Doom's movements.

"Days of Doom" is about the inevitability of endings and death (it opens with a quote from the late Doom-inspired rapper, MF Doom: "Living off borrowed time, the clock ticks faster"). In doing so, it confronts the ultimate contradiction of Doctor Doom; his name. "Doom" suggests a calamitous end, but he is someone who wants to build a better future. Doom, preparing to face Galactus and with the eyes of The Watcher, The Living Tribunal, and Eternity itself on him, declares that great men do not succumb to regret in their last moments, but "embrace Doom and laugh in its face."

Doctor Doom (2019) by Christopher Cantwell and Salvador Larroca

In the 2019 "Doctor Doom" series, a group called The Antlion Project has opened up a "controlled" black hole on the Moon to siphon off carbon emissions. Doom predicts this will fail because they didn't ask him for help. When the Antlion project is attacked with Latverian missiles, Doom is suspect no. 1. When other nations come knocking on Latveria, Doom surrenders — because he was framed.

Unlike the previous comics mentioned, "Doctor Doom" was an ongoing series. A day in life of Latveria could be a fine single issue (and it was, in John Byrne's "Interlude," aka "Fantastic Four" #258). For a sustained series, though, Doom needs more of a sustained drive, hence Cantwell stripping him of everything, from his resources to his control of Latveria, and giving him the concrete goal of proving his innocence. Larroca's art, which employs tracing for maximum realism, is not always flattering but he conjures up some unforgettable images, like Doom riding a bear horseback style.

Since Doom is the protagonist, you'd assume this series would be him at his most noble. Nope; it's Doom at his pettiest and he regularly inflicts suffering for minor slights. Cantwell's Doom reminds me of Ronan Farrow's 2023 New Yorker profile of Elon Musk, featuring this quote from Musk's fellow tech bro, OpenAI's Sam Altman: "Elon desperately wants the world to be saved. But only if he can be the one to save it."

Unlike Musk, Doom actually is a skilled inventor but the rest of the assessment applies, which is central to the comic's wild ending. It's too good for me not to talk about, but I also don't want to spoil this series. So, if you haven't read "Doctor Doom," stop reading here because there are spoilers ahead.

The ending of Doctor Doom, explained

Throughout "Doctor Doom," Victor sees visions of himself happily married with children and an unscarred face. Is this his future or mere hallucinations? In the 10th and final issue, Victor gets his answer. He finds himself in a world where he has reformed, leading not just Earth but the galaxy into a golden age; his earlier visions were glimpses of this other world. All it took was letting go of his anger and victim complex; as Doom's other self tells him, he could've easily healed his face but chooses the mask because it's a reminder that the world has wronged him.

Finally, Doom has proof he can create the world he's always wanted and be a beloved hero. All it takes is abandoning his current path and admitting his mistakes. Does he do it? Of course not; he murders his better self and then uses Galactus' Ultimate Nullifier to destroy the other universe and all who live in it. This jaw dropping ending underlines the difference between Doom and Marvel's other greatest villain, Magneto. Whereas Magneto believes in something greater than himself (mutantkind), Doom believes only in Doom — not even Victor Von Doom either, but Doom as the mask he's made to hide his insecurities.

"Doctor Doom" Volume 1 is titled "Pottersville," while Volume 2 bears the name "Bedford Falls," i.e. the names of the town in "It's A Wonderful Life." The former is the town without George Bailey (James Stewart), the latter is what it is with him. The dichotomy of these titles shows how this series was Doom getting the opposite wake-up call as George; the world with him in it is the bad one, but there's a chance to change. Instead, Doom proved there's no redemption for him — and I clapped as he did.