Immortal Thor Is The Marvel Comic For People Sick Of The MCU

The best days of the Marvel Cinematic Universe are behind it, and I don't just mean the fall from its decade-long box office throne. Any media that reaches pop culture omnipresence like Marvel movies did inspires a counterwave of backlash — it's just the way the discourse flows. And with the MCU, there's a lot to critique.

There's shoddy filmmaking, the centering of Marvel Studios president Kevin Feige as the creative glue, the cheap self-deprecating humor that's spread its roots across Hollywood (e.g. Netflix's live-action "Cowboy Bebop"), and the aimless, complicated-yet-simplistic narrative that exists in service of nothing but its further propagation. That last issue is inherited from Marvel Comics, yet if you dive into current Marvel comics, you'll find one all-too-aware series that is weaving MCU critique into its (meta)text. That series is Al Ewing's "Immortal Thor" (with artwork from Martin Cóccolo, Ibraim Roberson, Carlos Magno, and Valentina Pinti).

The MCU's solution for the so-so fan reaction to Thor was turning him into a comedy character; "Thor: Ragnarok" director Taika Waititi admits he saw the source material only as something to mock. This comedic turn played to Chris Hemsworth's acting strengths (until "Love and Thunder" anyway), but it lays bare the MCU's trusted hook: laugh at yourself and make the audience think they're in on the joke. Some, like "Avengers" writer/director Joss Whedon and "Guardians of the Galaxy" helmsman James Gunn, balance the humor with pathos, but most of the MCU doesn't even pretend to walk that line and instead collapses into a parodic husk.

In "Immortal Thor," the Thunderer's greatest adversary is that husk.

Marvel superheroes as modern mythology

Superheroes have often been described as "modern mythology." The fact that Marvel Comics directly incorporates the Norse God of Thunder while DC Comics draws on Greek myths for Wonder Woman feeds this argument. This notion is even uncritically presented in George Miller's "3000 Years of Longing," a movie all about how storytelling is a constant of history. (Miller himself was attached to a "Justice League" movie at one point.)

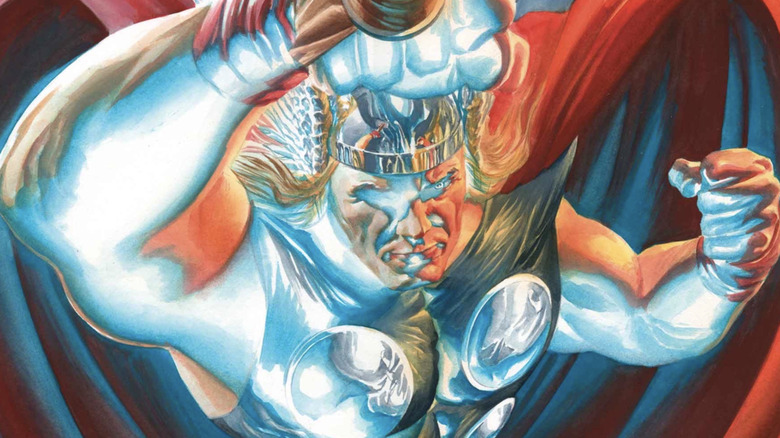

Al Ewing takes this argument into account. His prose in "Immortal Thor" is penned like that of an epic, dazzling the reader in equal measure as Alex Ross' painted covers and Cóccolo's sweeping interior art of battles and Thor soaring with the wind on his back. Ewing opens most issues with a relevant quote from Norse poetry book "The Elder Edda of Saemund Sigfusson," drawing a direct line from superheroes to those epic poems (and encouraging comic book fans to read more than just comics).

"Immortal Thor" is about the stories people tell (Thor's brother Loki is the God of Stories). Ewing is telling an epic story and his writing shows that pride, in stark contrast to the embarrassment and self-deprecation the MCU does when it gets weird. ("Spider-Man: No Way Home" using the name "Dr. Otto Octavius" as a punchline gave me one of the widest eyerolls of my lifetime.) Ewing doesn't, however, take the idea of superheroes as "modern myths" at face value. He digs in, unpacking what such a thesis means and without shushing arguments against it.

The foes of the Mighty Thor

The first trial for Thor in this series is Toranos, an elder God hailing from "Utgard" (in Norse myths, the third realm of Yggdrasil after Midgard and Asgard). Toranos, who dwarfs Thor in the same way the Son of Odin dwarfs us mortals, also commands the storm with greater experience and power than Thor does. He's also named after the Celtic God of Thunder (who wielded a wheel rather than a hammer). Different cultures create similar yet distinct myths, and those myths conflict.

Since Thor realizes he is just one permutation of the God of Thunder, in "Immortal Thor" #4-5, he calls down other Thunder Gods (including Storm of the X-Men) to defeat Toranos. However, the real threat to the Earth is more slow-boiling.

One of Thor's newer adversaries is Dario Agger (introduced by Jason Aaron and Esad Ribic in 2014), the CEO of energy company Roxxon (read: Exxon). He also possesses the power to turn into a Minotaur, and stays that way more often than not. The absurdity of a bull-headed man in an Armani suit is part of the bit. Agger stays transformed as a taunt, showing that no one with the power to arrest him cares or wants to challenge another member of the 0.1%, even though he's literally a monster.

Agger's goal? Hasten ecological collapse so as to make Roxxon's stock go higher and higher, then start over on another world and repeat. His paradise is glimpsed in "Immortal Thor" #9; a wasteland where the only remaining life is a dome containing picket fence suburbia; the rich live on borrowed luxury time while workers are chattel. Parody, or just a peek into the mind of the elite, where humanity exists to serve capital, not the other way around?

How can the Immortal Thor save the Earth?

Toranos was summoned by Gaea — the spirit of the Earth, a fellow Elder God, and Thor's mother — in hopes he would destroy the humans that poison her. After a mother-son chat, Thor sets off to once more clash with Agger. This is where the meta text of "Immortal Thor" takes hold.

Ewing previously used Agger as a villain in his series "Immortal Hulk." Halfway through that 50-issue run, Bruce Banner decides to save the world by smashing capitalism. Agger, who proclaims narrative is Roxxon's "most powerful product," is only alarmed once the Hulk destroys the servers for the company's social media platforms, since these are the tools that slip his agenda into the masses' minds. (One of the most terrifying "Immortal Hulk" issues is #28, where a middle-aged security guard, radicalized by right-wing internet propaganda, shoots his own daughter when he spots her at an anti-Roxxon protest, telling himself that the "Devil crawled inside her.")

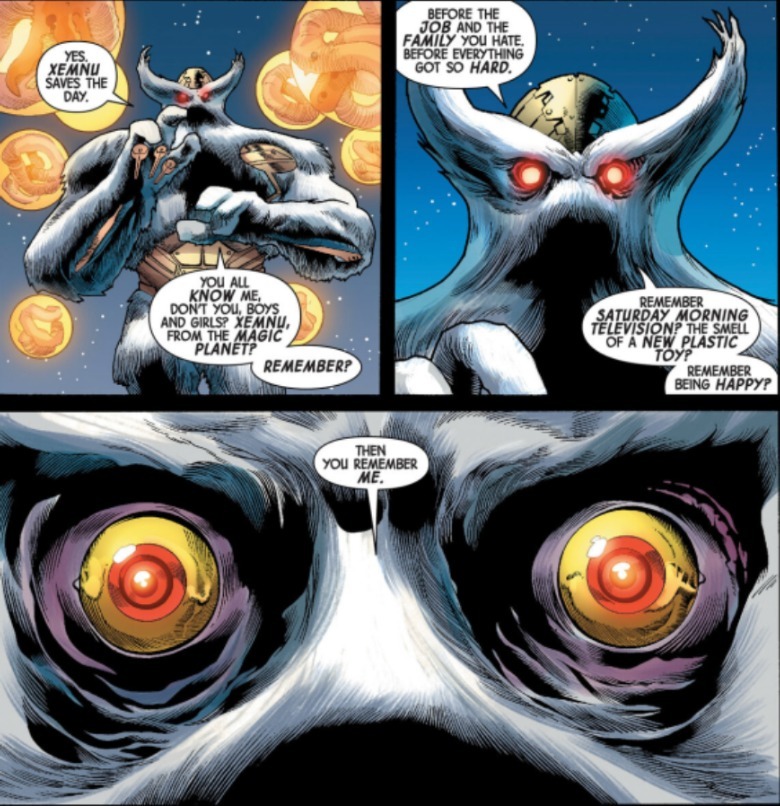

In his brief turn as the big bad of "Immortal Hulk," Agger recruited the alien Xemnu, a white-furred Yeti-like monster with psychic powers, to be "his" Hulk. Granted the reach of broadcast television, Xemnu beamed out false memories worldwide of himself as Earth's most beloved hero, encouraging the masses to let nostalgia rule their minds and fall back into the slumber that Hulk had been trying to wake them up from.

Agger's involvement reveals "Immortal Thor" as a thematic sequel to "Immortal Hulk." Proving once more that billionaires don't climb the top with imagination, his plan is basically the same, just retargeted from the Hulk to Thor. He purchases the in-universe Marvel Comics, which still publishes Thor's adventures (but as records of history) and reboots them to be more Roxxon-friendly. And he doesn't stop at propaganda.

Disney and the MCU have taken over Marvel Comics

Agger partners with Amora the Enchantress, who enchants Roxxon's Thor comics. Her spell means that the more people read them, the more the comics resemble reality. "Immortal Thor" #10 features Thor fighting "Chad Hammer," the version of himself summoned out of "Roxxon Presents: Thor" #1.

Ewing hammers in his point by writing "Roxxon Presents: Thor" as a real comic (published between the ninth and tenth issues of "Immortal Thor"). The issue is drawn by Greg Land, an artist who is famous for his lazy traced drawings; him pencilling this soulless comic feels like an extra layer of self-parody. Most of "Roxxon Presents: Thor" is terrible schlock and meant to be, but for one moment, Thor breaks free of the comic's influence and Dario explains the writing's strength.

"Thor" as published by Roxxon has all the hallmarks of the MCU, from the light (humor that points back at itself) to the insidious (social justice "villains" who "go too far" in upsetting the status quo); the comic's insight is showing how the former shields the latter, making audiences come back to hear messages against their own good. The comic even infects the "real" Thor, compelling him to speak in all the pithy lines we associate with the MCU's self-aware humor: "That just happened," "He's right behind me, isn't he?" etc. The MCU, Disney's preferred interpretation of the Marvel Universe, holds reign over how the comics are made, because the MCU has become the version of this world that most people recognize.

Are Marvel superheroes myths or content?

For me, the greatest problem with the idea of superheroes as "modern mythology" is that myths belong to the public, while these characters do not. When Stan Lee and Jack Kirby incorporated Thor into the Marvel Comics universe back in 1962, they privatized a legend. Disney's ownership of Marvel takes that a step further. These comics are longer scrappy pulp in a niche medium; they're the fuel of the greatest corporate movie machine on Earth, so all edges must be sanded off lest you alienate just one consumer.

It's a content factory, and as Ewing (via one of Agger's taunts to Thor) brilliantly observes in "Immortal Thor" #9, that word carries a double meaning: "Art. I never liked that world. I prefer 'content.' It's the unit of product to be sold ... and the feeling you're selling with it. In such an anxious world, who doesn't want to be content?"

While superhero comics are printed to ensure money prints alongside them, myths were told and spread to explain the world around us. The Greek story of Persephone and Hades "explains" the changing of the seasons. Even today, when something bad happens in a faithful person's life, they assuage the pain with the chant that it's all part of God's plan.

What do superheroes explain? How do they help us make sense of our world, aside from instilling young boys with power fantasies? Ewing and "Immortal Thor" offer an answer by incorporating the machinery and effects of comics publication into narrative. Superheroes are less an evolution of myths, and more like the bread and circuses of ancient Rome. It's marvelous how violent entertainment can make us all so content.

How to be worthy of the power of Thor

But can "Immortal Thor" escape that it, too, is a Marvel Comic? Dario Agger is obviously a villain, and representative of real people that Ewing clearly can't stand, but does "Roxxon Presents: Thor" inadvertently give voice to that which it's critiquing? When Agger claims that self-parody is an effective weapon for a brand, that applies too to Marvel itself allowing the criticism of its storytelling to be the backbone of "Immortal Thor." Agger's monologue might as well be Disney speaking to the reader.

Ewing is kindred to Agger, using comic publishing as a vehicle for his worldview (even if those worldviews have nothing in common). Still, the high quality of his writing has one primary effect: incentivizing people to buy more Marvel comics, giving more money to the brand and its Mouse-eared parent company. It doesn't matter if their product disparages them, just as long as the cash flows.

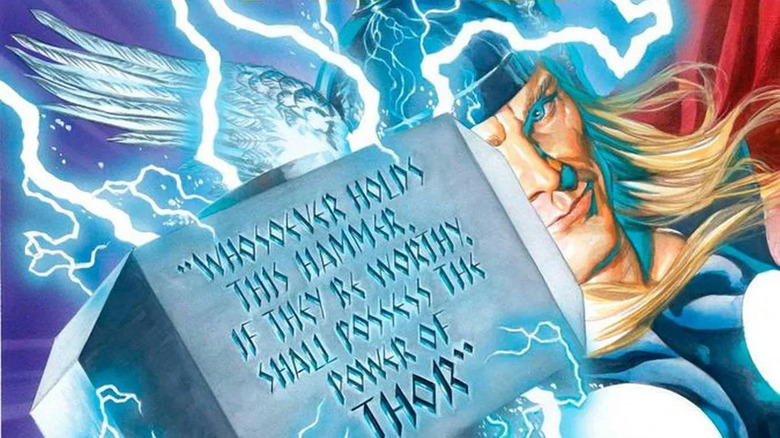

Thor has been around far longer than Marvel Comics, and he'll be around after history washes away these comics. But in every form, he's only fictional, and while fiction holds power over our minds, that's all the power it has. No hammer-wielding Thunder God is coming to save you, but maybe he can inspire you to save yourself.

"Immortal Thor" #12 publishes on June 19, 2024.