Rod Serling Had Some Regrets About The Twilight Zone's Most Nostalgic Episode

This post contains spoilers for "The Twilight Zone" season 1, episode 5: "Walking Distance."

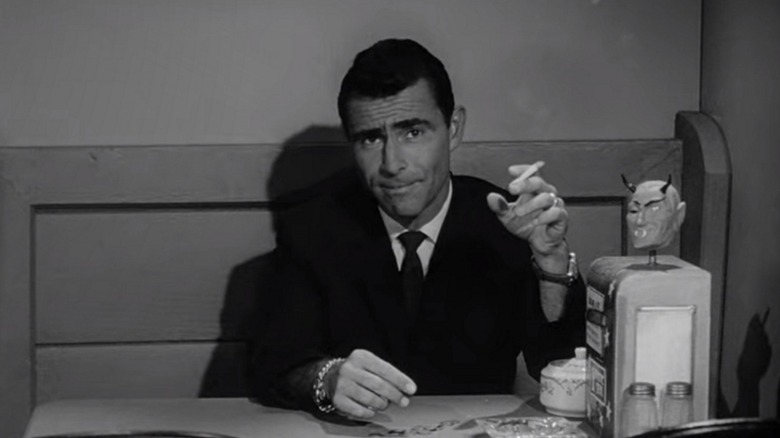

One of the most beloved episodes of "The Twilight Zone" was also one of its least terrifying. "Walking Distance," a season 1 episode about a man who unwittingly travels back in time and revisits his childhood, is widely praised for its melancholy, nostalgic themes. The show's creator, Rod Serling, also generally looks back at it fondly. As his daughter Anne Serling explained in a 2019 interview:

"There are so many pieces of my father in 'Walking Distance.' When he was in the war, his father had a heart attack, and he wasn't able to get leave to go see him. By the time he got home, his father had died. Those trips to Binghamton were his way of going back in time. He would sit at the park and just remember the idyllic childhood that was cut short by going into the war."

Serling himself has stated that the episode hits hard on his own tendency towards nostalgia. "I hunger to go back to knickers and nickel ice cream cones," he once said. "It struck me that all of us have a deep feeling to go back as we remember it." Despite all this, Serling isn't blinded by nostalgia when it comes to the episode itself. He was always able to be critical of his past work, and "Walking Distance" was no exception. In particular, he believed it was weakened slightly by some shoddy, over-expository writing.

Rod Serling's problem was the execution

As a former student of Rod Serling recounted, Rod Serling once played "Walking Distance" to his class of aspiring writers and asked them to pick apart the flaws, the first of which was apparently the opening scene where Martin Sloan (Gig Young) tells the gas station attendant all about his problems at his job and the stresses of his adult life. "WHO would do that? Why would Martin tell his whole life story to a frickin' gas station guy?" Serling reportedly said. "This was just used as a lazy writer's way to provide plot exposition."

Serling also didn't like the scene at the drug store in which Martin tells the counterman a bunch of things that should be utterly bizarre from the counterman's perspective. As his former student recounted, "Martin mentions that the drug store owner was dead, when the counterman knew he was very much alive up in his office. In this case, Rod felt the counter man should have reacted differently and questioned Martin, but didn't." Serling's biggest problem with the episode, however, was Martin's reaction upon meeting his alive-again parents:

"Serling felt that Martin's mind should and would have been totally blown at that point. That he would NOT be able to function normally... He said the whole episode should have built up to that scene. That it should have ended the episode, that nothing he could have written would top that. 'As an adult meeting your parents who you loved more than anything. Now they're alive again and right in front of you.'"

Was Serling a good judge of his own work?

I'm inclined to agree with Serling's take on the episode, although I should confess that I'm the one of the few "Twilight Zone" fans who never liked "Walking Distance" in the first place. As someone with no wish to revisit his childhood, who remembers the period as being confusing and stressful rather than happy and carefree, this episode's repeated declarations that childhood is the most wonderful period of your life have never rung true to me. The episode treats the desire to return to your childhood as a universal wish that everyone has, but a happy-go-lucky childhood is not actually a universal experience.

Even beyond my distrust of nostalgia, I'd say that the clunky exposition was a constant problem in "The Twilight Zone." From the very first episode, where the main character in the empty simulation is monologuing to nobody, the show had a tendency to have its characters talk more than felt natural. It's a forgivable trend, given how young the medium of TV still was in the early '60s and how little time each episode had to set up its speculative premise, but it still dates the series a bit.

In general, the show's flaws tend to be glossed over today, which is why it's almost refreshing to see that Serling wasn't blinded by nostalgia. "Of the 156 episodes of 'The Twilight Zone' I'm very proud of about 25% of them," Serling reportedly told his students. "50% of them were acceptable. They probably held the viewer's interest for the length of the episode, but not one that would be remembered for any length of time, and 25% of the episodes were pure crap." (Note: according to the student recalling this, Serling used a harsher word than "crap.")

Serling preferred 'A Stop At Willoughby'

Spoilers for "A Stop at Willoughby" below.

Serling told his students that the later episode, "A Stop at Willoughby," was stronger than "Walking Distance." It's not 100% clear why he thought this, although a good reason might be that the episode had far less clunky exposition. The main character Gart's terrible adult life is shown to us in detail, including his memorable boss with his "Push push push!" mantra. Whereas Martin's stressful life in "Walking Distance" is told to us via monologue, kept deliberately vague in an attempt to be as relatable and universal as possible, Gart's life in "Willoughby" is extremely specific: he's sad not necessarily because he's older, but because he feels pressured into a complicated high-class job and lifestyle he never really wanted.

Another benefit of "Willoughby," at least for the nostalgia-haters in the audience, is just how much it stomps on the idea of some mythical past place where everything was perfect. "Walking Distance" may eventually conclude that it's bad to dwell on the past, but it takes its sweet time in getting there; "Willoughby" makes it clear early on just how much this seemingly-perfect 1880 small town is an unreachable fantasy. There is no "just stopping by" in Willoughby; the moment Gart steps off the train and walks into town, he's dead. One can argue this is still a happy ending, as Gart seemingly ends up in a heaven-esque afterlife, but the fact that it ends with his dead body being driven away implies otherwise. Both "Walking Distance" and "Willoughby" conclude that there is no quick and easy way to solve the problems in your life, but I (and Serling, by the sound of it) would argue that "Willoughby" makes its argument with far more precision.