The Most Confusing Parts Of David Lynch's Blue Velvet, Explained

David Lynch's cinematic world tiptoes between stark reality and nightmarish dreams. While some Lynchian small towns are infused with romanticism despite harboring great evils (such as Twin Peaks), others, like Lumberton, weave an insincere facade with its aura of suburban bliss. This sentiment forms the crux of Lynch's sensational, often misunderstood "Blue Velvet." Most of Lynch's work eludes objective analysis, and his ideas, although abstract, are always tethered to reality in essential, terrifying ways. Although "Blue Velvet" features one of the most straightforward narratives in Lynch's body of work — it is neither as labyrinthine nor heady as "Mulholland Drive" or "Inland Empire"— the film's graphic depictions of psychosexual impulses can confuse and alienate, with the real and fantastical merging to create a disorienting experience.

The core themes in "Blue Velvet" can dramatically change with the viewer's perspective, as Lynch pushes the traditional ideas of narrative logic to extremes. Here, dreams take center stage, and surrealist imagery is used often to evoke a deep, subconscious reaction within us. This is why phrases like "What does this mean?" or "Here is what happened" are futile, as real-world logic cannot be applied to Lynchian small towns and the events that define them. However, we can attempt to dissect the broader themes in "Blue Velvet," what they might mean within the context of the events that we do understand, and how Lynch uses archetypal contrasts to depict nostalgia towards the past (that is not as rosy as it seems). Here are some of the most confusing parts of the film, explained.

What does the rotting, severed ear in Blue Velvet symbolize?

The opening of "Blue Velvet" is filled with nostalgic romanticism, replete with white picket fences, vibrant red roses, and beautiful lawns that make up the fantasy of American suburbia. This dream is shattered almost immediately when Mr. Beaumont has a stroke while watering his lawn, with the camera swerving to the rotten undergrowth concealing a grimy underbelly. When his son Jeffrey Beaumont (Kyle MacLachlan) walks through the trails in his neighborhood, he discovers a severed ear infested with ants, and is fascinated with its presence and what it represents. Although the severed ear acts as the catalyst for Jeffrey's investigation, it also marks his journey to the other side, which lures him with promises of rule-breaking titillation.

Lynch uses the ear canal as a bridge to a realm parallel to the one we are introduced to, like a dark mirror steeped in blunt violence and strange impulses. This hidden realm exposes the hypocrisies of Lumbertown while holding no space for innocence or naiveté. Jeffrey's curious tumble into this seedy underbelly can be viewed as an uncomfortable rite of passage, through which he is exposed to psychosexual violence and desire (often interconnected in this shadow world). A brand of Lynchian surrealism also defines this reality, as Jeffrey finds himself in mundane situations that have a dreamlike quality, such as when Dean Stockwell's flamboyant character mimes to Roy Orbison's "In Dreams," which moves Jeffrey deeply to pursue unattainable nostalgia. In essence, the severed ear becomes a vessel for transition into emotions that are deeply unsettling yet embedded into the human experience.

What drives Frank Booth, the symbol of unchecked evil

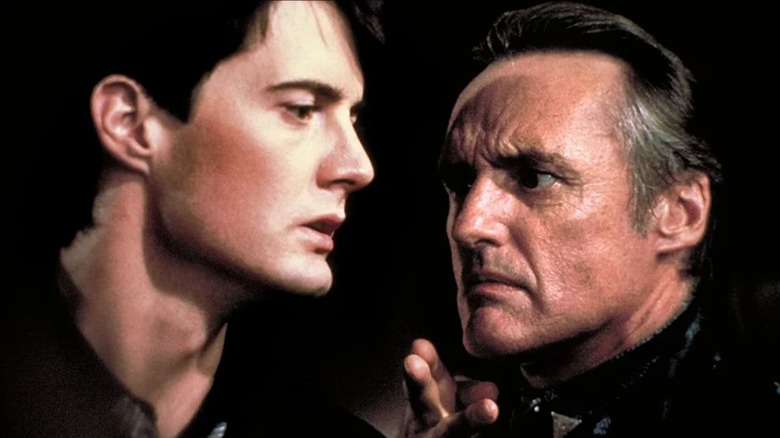

Jeffrey's first clue to solving the mystery is lounge performer Dorothy (Isabella Rossellini), a woman he wants to desperately save from Frank Booth (Dennis Hopper), a sadistic aggressor in control of Dorothy's fate and autonomy. Initially, Frank appears as the antithesis to Jeffrey's gullible heroism — the prime suspect to his rookie detective — whose evil feels cursed in a town believed to be picture-perfect. Frank's sexuality is only channeled through abuse and anger, and the strange gas he huffs between these acts of brutality alienates him from how most humans function. This man breathes unlike anyone and emotes in unpredictable extremes, exposing deep psychosexual repression and twisted ideas of masculinity. Tender vulnerability is not in Frank's vocabulary: He represents unchecked evil that is too afraid of the light, as it might expose the delusions that contribute to his aggressive, volatile nature.

Frank's obsession with Dorothy extends to Jeffrey, as he not only shatters his fantasy of control over her but is also an object of Frank's repressed desires (which he expresses through bursts of rage charged with erotic toxicity). Whenever Frank is too close to tasting something truly beautiful, like a performance of "Blue Velvet" in the club, or the moving mime performance of "In Dreams," he lashes out to preserve his fragile reality that thrives on the Freudian pleasure principle. Although Jeffrey is both repulsed and fascinated by Frank's existence, he must eliminate Frank's unchecked id (instinct) to return to his fantastical world of white picket fences and blissful ignorance. Once the Freudian id is destroyed, the false normalcy of Jeffrey's ego (logic) takes over, bringing the adventure to an end.

Candles represent the interplay between light and dark in Blue Velvet

Lynch often uses striking visual motifs to convey ongoing themes that invite diverse interpretations, which are then used as the "key" to unlocking a particular work. For example, "Lost Highway" repeatedly focuses on a Lynchian version of the Yellow Brick Road, which stretches endlessly into the night (perhaps representing the depth of our unconscious desires). That said, it is problematic to attach a motif to a fixed meaning, as Lynch's films encourage us to experience them without pretense. The aim is to feel and intuit while keeping an open mind, as opposed to sleuthing obsessively to solve a logic puzzle.

With this in mind, the candle imagery in "Blue Velvet" might be interpreted in a few ways. The most prominent use of shadows and light is injected into Jeffrey's journey towards the darker corners of society he was previously unaware of. As shadows swallow him quite literally, and he hits Dorothy during sex, the candle near him snuffs out. This candle had burnt bright up until this point, the snuffed flame signifying a point of no return for Jeffrey. When he hits Dorothy, Jeffrey unconsciously mimics abuse and ends up participating in a toxic cycle that appears to be never-ending.

As for Frank, he is always framed in darkness, even when there is a light source near him. "Now it's dark," he states, after horrifically assaulting Dorothy, the candle near him roaring as a tone-setter for his ominous presence. This same roaring means something entirely different for Jeffrey, as the strong, passionate flame is used as a symbol of his grounded morality, which gradually flickers and eventually gets extinguished.

What do Dorothy and Sandy represent in Jeffrey's journey?

Lynch frames the two women in "Blue Velvet" through the lens of the Madonna-whore complex, where women are viewed in patriarchal extremes that lead to dehumanizing archetypes. For Jeffrey, Dorothy represents a seductive fantasy with boundary-pushing attraction and repulsion, while Sandy (Laura Dern) becomes the model for sexual innocence, embodying the "girl next door" archetype. Jeffrey alternates between the two women after being introduced to the darkness of suburban reality, and his introduction to Dorothy is through a thinly-veiled ruse that ends in voyeurism (where he witnesses the depravities of this world firsthand). If Jeffrey's tumble into this rabbit hole is a rite of passage, then his relationship with Dorothy is a transition into adulthood. This personal arc becomes complete with an understanding of intense sexual dynamics, where the line between sadomasochism and unchecked abuse is blurred.

After Jeffrey hits Dorothy during sex (after she asks him to), he is crippled by the guilt and shame of the act and seeks temporary refuge in Sandy, who symbolizes an unscathed return to the mundane. However, their relationship is also transgressive, as Sandy already has a boyfriend, and her meetings with Jeffrey under the pretext of investigating the ear lead to something tangible. For Jeffrey, Sandy also upholds the beauty of the American Dream in its purest form, which is why he returns to her in the end. Due to their connected escapism, the two of them can choose to turn a blind eye to the horrors they have experienced, either directly or by proxy.

Sandy's idealistic dream, and the robins at the end of Blue Velvet

At one point, Jeffrey confides in Sandy about the horrors he has witnessed at Dorothy's apartment, and how it has rattled his perception of the world. In response, Sandy talks about a dream in which the world is plagued by darkness, as there are no robins in sight. These birds, who represent true love, suddenly burst through the dark in her dream, banishing the ugly reality of the world forever. Sandy ends her musing by stating that love can make all the difference, even if the wait for such a sublime silver lining can feel long and hopeless.

In a surreal fashion, Sandy's gullible (but hopeful) dream about the robins representing everlasting love comes true, as we can see the birds flapping around her windowsill towards the end. For Sandy, this is an indication that love does make all the difference and that her reconciliation with Jeffrey is worth it. However, the robins are a facade, their symbolic hopefulness hiding the ugly reality of the circle of life. Both Sandy and Jeffrey willfully ignore the violence inherent in the act of the robin eating a worm, just like they have buried the unsavory underbelly they've witnessed firsthand. Jeffrey's transgressions, and the horrors experienced by Dorothy, are suddenly forgiven and forgotten. In this illusory fantasy that makes up their reality, ignorance is bliss.

As with any false sense of comfort or happiness, this illusion is bound to shatter at some point. Perhaps, it will take another severed ear disrupting the harmonic beauty of the suburban lawns to plunge Lumberton back into chaos.

What happens to Dorothy and her family at the end of Blue Velvet?

The severed ear that triggers Jeffrey's journey belongs to Donald Wallens, Dorothy's husband, who was kidnapped by Frank (who also kidnapped Dorothy's son, Donnie). Jeffrey theorizes that Frank must have kidnapped them to coerce Dorothy and intimidate her, although the specifics of this are not spelled out. Towards the end, Jeffrey enters Dorothy's apartment to find Donald dead, his body tied up and a gunshot wound visible on his forehead. This might have been Frank's way of punishing Dorothy for getting Jeffrey involved, as the latter's presence heightens Frank's agitation and feeds into his repulsive expression of psychosexuality.

In the end, with the arrival of the robins, the world seems to return to normal. Dorothy is reunited with her son and seems relieved that the nightmare is over. As Jeffrey kills Frank during the climax, there are no more monsters to be wary of, at least for the moment. However, as per the above mentioned illusory robin theory, this sense of security feels false, as Dorothy is never granted closure, and the death of her abuser does not erase the trauma she has undergone. Her husband's murder, along with Frank's brutality, will haunt her, as society is harsh and unkind to victims of patriarchal abuse.

While Sandy and Jeffrey can afford to forgive and forget, Dorothy cannot, as she has yet to process these intense emotions on her own, along with the grief of losing her husband. Her reunion with her son is the only true ray of hope in this scenario, as this bond of unconditional love is Dorothy's only solace in a world that is pretending to be a safe haven engulfed in light. Interestingly, Lynch talked about the what-comes-next aspect for Dorothy in an interview with Rolling Stone, emphasizing the "room to dream" after this surreal ending:

"Endings can leave room to dream [...] You can wonder after what Dorothy's gone through what her life would be. And each person can wonder along."

Absurdity and surrealist subversion in Blue Velvet

As I mentioned earlier, there are no objective answers to explain the cyclical, interconnected realities in "Blue Velvet," as heightened imagery is an important part of the film's visual and thematic fabric. Some aspects of the film are heartbreakingly sincere, such as Sandy's dream of darkness dispersing with the arrival of robins, while others highlight the cruel illusions of suburban fantasies that keep its transgressions hidden. These predatory, bug-like forces lurk beneath the facade, and people like Jeffrey often venture into these underbellies while pretending to be someone they are not (such as his ruse of being an exterminator when he investigates Dorothy's apartment). Over time, these bug metaphors become more intense, with the yellow man's presence hovering in the corners of the frame until he is squashed towards the end.

Jeffrey, who needs to step up after his father's stroke, gets the opportunity to look into the void and understand the discomfiting extremes of human nature. However, he is far from a mute observer. He is an active participant who is caught between being man and beast, where redemption only comes after he uproots evil and re-assimilates into the fantasy of what is considered "normal". These subversions are meant to unsettle, as people cannot emerge unharmed after a journey that changes who they are. With the characters' core identities compromised, this also changes how they decode and perceive others around them.

In the end, the comfort of the blue velvet is only temporary, as it also carries markers of violence: A constant reminder of the monstrosities of fellow man, and that of our own.