The Best Version Of The Star Wars Prequels Came In A Classic Manga Series

"Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace" is back in theaters for its 25th anniversary this week. Some "Star Wars" fans will doubtlessly be celebrating (and turning out to make "The Phantom Menace" a box office smash once more) and I won't begrudge them that. But sorry, I'm still not on board with prequel trilogy revisionism.

I was born the same year as "The Phantom Menace" premiered — it's the movie that introduced me to "Star Wars." I know my generation has largely accepted the prequels, but while I can appreciate their ideas, they're still too hindered by shoddy storytelling and flat acting for me to sign off on the execution. "Star Wars: The Clone Wars" is good (see our choices for best episodes here), but a cartoon spin-off set between the cracks of the "Star Wars" saga can do only so much restorative surgery.

In a macro-sense, the prequels are about the fall of a democracy (something director George Lucas had no clue would be so resonant). This fall is parallel to the movies' interpersonal stakes: the demise of a friendship, of the brotherhood between Jedi Knights Obi-Wan Kenobi (Ewan McGregor) and Anakin Skywalker (Hayden Christensen) when the latter becomes Darth Vader.

Everyone and their dog has a "How to fix the 'Star Wars' prequels" pitch, but what if I told you there was another story out there that already accomplished that? A fantasy story that took into itself the same emotional core about two friends, and how one of them became a monster, then carried it to masterful results?

That story is the dark fantasy manga "Berserk." If you didn't cry like you wanted to when Anakin and Obi-Wan duel in "Revenge of the Sith," "The Golden Age" arc of "Berserk" will wring those tears out of you.

What is Berserk about?

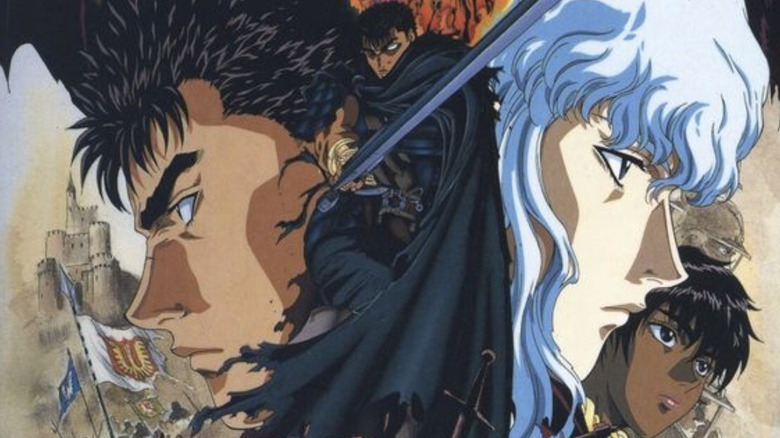

"Berserk" was authored by the late Kentaro Miura. Set in a Medieval Europe-inspired fantasy world, the first three volumes follow a lone "Black Swordsman" named Guts; he's got one eye, a mechanical right arm, and a violent disposition. Every night, he slays ravenous demons who follow him wherever he goes.

The manga starts in media res, but at the end of volume 3 — and until volume 14 — it flashes back to explain how Guts became the man we meet him as. This arc is collectively called "The Golden Age" and make no mistake, it is a prequel. Trying to read "Berserk" chronologically, rather than in the publication sequence, is a mistake.

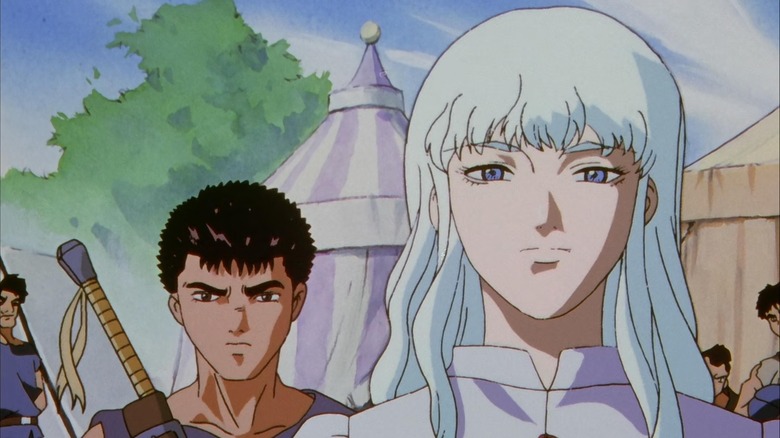

During "The Golden Age," a teenage Guts — already a warrior — joins a mercenary group, The Band of the Hawk. The Hawks are led by the charismatic Griffith, who wishes to one day become a king. Guts grows close with both Griffith and his right-hand woman Casca, while the Hawks ascend the Hawks ascend as the most celebrated heroes in the kingdom of Midland, earning the favor of the royal family. Then, Guts decides to leave and chart his own destiny. A spurned Griffith recklessly sleeps with the Midland Princess Charlotte and spends a year imprisoned and tortured.

The Hawks (led by Casca and a returned Guts) rescue Griffith, but as a shell of his former self, his dream is out of reach. So, he makes a deal with four devils called the God Hand. In the worst anime/manga betrayal ever, Griffith sacrifices all his followers to be reborn as the fifth finger of the God Hand: Femto, clad in a black avian shell resembling Griffith's old battle armor (but now with real wings). Guts is one of the Hawks' only survivors and dedicates his life to revenge against Griffith.

How Star Wars could've inspired Berserk

Guts is similar to Ash Williams from "Evil Dead," another unlucky one-armed demon slayer. (Miura even noticed the resemblance after "Evil Dead II" came out and worried he might be sued.) Griffith, though, reminds me most of Darth Vader. Miura said "Star Wars" was his "all-time favorite movie." Born in 1966, he would've been a 12-year-old boy when "Star Wars" was first released in Japan — exactly the right person to have his life changed by the movie.

"Berserk" began publication in 1989 and "The Golden Age" wrapped in 1996 (months before the first "Berserk" anime adaptation premiered). So it couldn't have been Miura responding to the prequels and trying to tell a better "downfall of a hero" story. Still, I think his own imagination about how Darth Vader fell to the dark side would've influenced his story.

After all, Miura was a first-generation "Star Wars" fan, who would've watched the original trilogy as it was released and lived with the mystery of the series' backstory for years. For younger viewers like myself, who've always known the prequels as part of the canon, this sounds like a foreign experience, but that is the experience of the older fans. Even if they'd been better made, the prequels might've always disappointed some because no film can compete with the affection you hold for your own imagination.

Miura wouldn't have been the only mangaka who let his love for "Star Wars" guide his story either; "Fullmetal Alchemist" author Hiromu Arakawa considers Darth Vader the best villain ever.

Obi-Wan and Anakin's Battle of the Heroes falls flat

In "Return of the Jedi," Obi-Wan (Alec Guinness) recounts with wistful regret how Anakin was his student, how he thought he could train him with skill and wisdom: "I was wrong." As Luke (Mark Hamill) tries to lure his father away from the dark side, the first chink in Vader's armor falls with these words: "Obi-Wan once thought as you do." The seeds were there for a tear-jerking tragedy, yet we barely got the facsimile of one.

Granted, the "Star Wars" prequels didn't have an easy task. The films needed to convince their audience of Anakin as both a great hero and that said hero would become a villain. They fall short, both due to poor pacing and acting. "The Phantom Menace" infamously opens with Anakin (Jake Lloyd) as a nine-year-old child, forcing "Episode II — Attack of the Clones" to jump ahead ten years to get him up to plausible "fall to the dark side" age. By that point, the audience is robbed of the chance to see Anakin and Obi-Wan's friendship blossom and endure.

"Revenge of the Sith" has the narrative of a checklist, with Lucas realizing how he needs to set things in place for the original trilogy without the time he wasted in the first two movies. The first half of "Episode III" at least gives Obi-Wan and Anakin some friendly banter and a shared emotional connection here and there, but it's not enough that you care about these two remaining friends. When Obi-Wan declares, "You were my brother, Anakin, I loved you!", you don't believe him no matter how hard Ewan McGregor is trying (and he's trying very hard).

Guts and Griffith are what Obi-Wan and Anakin should have been

Now, Guts and Griffith are not perfect analogs for Obi-Wan and Anakin. Griffith isn't Guts' mentor per se, but he has the seniority in their relationship. Unlike "Star Wars," it's not the student who falls to the dark side. "Berserk" also had more time for "The Golden Age" (2000+ pages' worth) than "Star Wars" had with the prequels (about six hours total). Mangaka's art is more individually expressive than a filmmaker's too; the entire world emerges from their hand, with no limitations brought about by logistical practicalities or the need to rely on others.

With that out of the way: the main difference is how much you care about Guts and Griffith. When you read "Berserk," it makes total sense why these two men grow close and you want them to stay that way. Basically, they're each others' first friend. Guts is an orphan raised by abusive mercenaries; he's been fighting since he was born. Griffith was a peasant child who lived beneath a castle on a hill; staring at it every day made him desire it. Guts has never bonded with anyone because life taught him to avoid connections, while Griffith's ambitions distorted his view on his comrades-in-arms; they worship him and he sees them as treasured tools, not brothers.

Guts is shanghaied into the Hawks after losing a duel with Griffith; he's not there by choice, but he too is swept up by Griffith's dream and charisma — the first time someone has had that impression on him. In winning Guts over, Griffith opens up to him and they bond.

Why Guts and Griffith became enemies

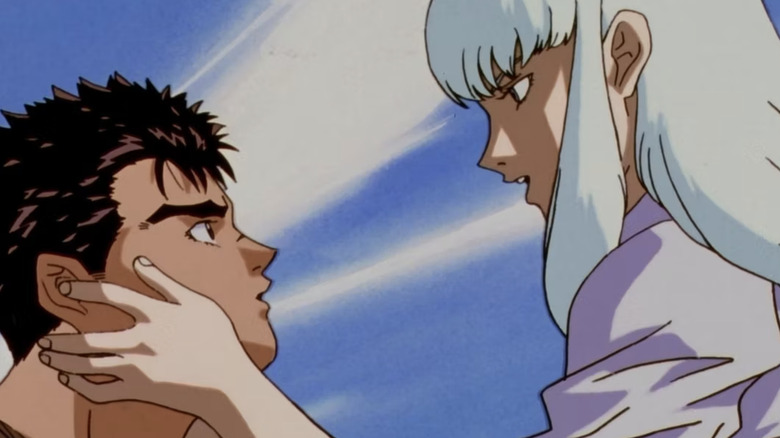

Griffith inspires Guts to find his own dream, his own reason for living (especially after he overhears Griffith saying that he could never call someone without a dream a friend), but his need to prove himself to Griffith destroys their friendship. Griffith feels he can't lose Guts. That means he's willing to sacrifice himself for Guts (as he almost does in battle), but he also won't let him live anywhere except by his side. When Griffith learns of Guts' plans to leave, he draws his sword — and loses. That destroys him, the first time in a long time he's been denied something he wants. Griffith's need to possess Guts kickstarts the chain of events that leaves him unable to grasp anything else.

The original "Star Wars" trilogy established that Darth Vader was frail and scarred beneath his armor. We see why in "Revenge of the Sith" when Obi-Wan maims Anakin in their duel and leaves his former friend to burn to death. Anakin's fall into a metaphorical Hell being cemented with fire is a nice touch, but Griffith's devolution is even deeper.

The torture doesn't just inflict pain on Griffith, it destroys his dream. Griffith rallied support with his charisma, his voice, and his good looks — so his tongue was cut out and his face peeled off. He led his troops from the front with his remarkable swordsmanship; with his tendons cut, he couldn't even walk, much less fight. Just before he meets the God Hand, Griffith falls from a cliff. His brief flight ends soon, and he lands with a broken arm; the White Hawk's wings that were meant to carry him toward his soaring dream have been clipped.

What Griffith sacrifices in Berserk

Anakin's fall in "Revenge of the Sith" is rushed and truncated to a single driving cause; he wants to save his wife, Padmé (Natalie Portman) after he sees visions of her dying. Even though Miura knew the endpoint Griffith's story had to reach in "The Golden Age" (such is the will of causality), he takes his time getting there; both in building Griffith up and tearing him down. We see his ruthless drive, which is fueled only further by the guilt of the soldiers he's lost; they fought for his dream so he better make their deaths count.

Even before he makes the sacrifice, we can tell how he now looks at Guts with silent hatred (Guts himself is none the wiser). Casca looks at Griffith with pity where once she revered him. Instead, her eyes now twinkle brightest for Guts, and Griffith can't stand it. He never loved Casca like she did him, but like many greedy men, his possessiveness comes out most when he loses something he thought would always be his.

Imagine if you were brought to your absolute lowest point. Then your salvation comes, and all it takes is a sacrifice. Void, leader of the God Hand, tells Griffith: "If your dream still lives, if that castle still gleams just as brightly in your eyes, then it is your obligation to lay the stones that surround you now." Those stones are the Hawks, including Guts. Griffith claims Guts once made him forget his dream, but he makes his choice to sacrifice, leaving the Hawks as food for the God Hand's Apostles.

Why Griffith did everything wrong in Berserk

Griffith's decision is unforgivable, but you understand why he made it and how the totality of his character arc led him there, with no bumps in the road to ever make you question it. It's the most detailed, psychologically consistent, and horrifying "corruption arc" I've ever read. "Star Wars" never quite threaded that needle with Anakin's fall, particularly his most infamous act: killing several Jedi children in "Revenge of the Sith." It's shocking but not quite convincing as his first act of great evil so soon after his fall.

Griffith, remade into Femto, christens his new name with an act just as vile; raping Casca in front of Guts, who is held down by demons and powerless to save her. (It's extra painful since Guts is a sexual assault survivor himself and once again experiences that same helplessness, only this time someone he loves is hurt too.) Why? Because just like Griffith wouldn't accept any future but a kingly one, he couldn't live without being the most important person in both Guts and Casca's lives. He poisons their love to punish the two of them for choosing each other over him.

The tragedy of Berserk eclipses Star Wars

The climax of "The Golden Age" is tragic not just because of the suffering inflicted on the story's heroes, but because until Guts sees what Griffith has become, he still believes in their friendship. As the Hawks are massacred around him, Guts is trying to "free" Griffith, unaware he's condemned them all. As part of the film's speedrun pacing, "Revenge of the Sith" has Obi-Wan and Anakin quickly devolve into trying to murder each other. In their last talk before their duel, Anakin boasts of his power while Obi-Wan admonishes him. There's not much sense in a teacher trying to connect with a beloved student, to pull them back from a ledge, only to be crushed when he realizes they've already fallen off of it. That's the sense you get of the story in "Return of the Jedi," but it's not what was delivered.

The "Star Wars" prequels don't convince me that Obi-Wan and Anakin ever loved each other, but I believe that Guts indeed loved Griffith. Betrayal by someone you love is an easy path to hate, and "Berserk" fans hate Griffith to the degree I wish I hated Darth Vader after the prequels.