X-Men '97 Retains One Of Magneto's Defining (And Tragic) Character Details

This article contains spoilers for "X-Men '97."

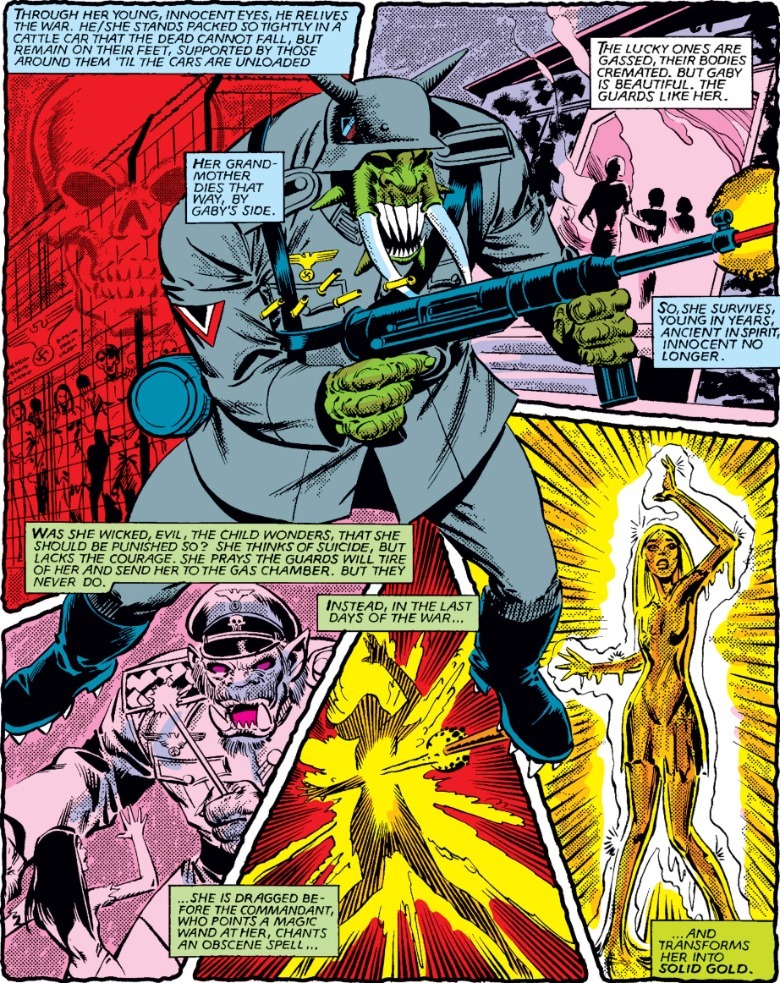

Magneto of "X-Men" has one of the most brilliant backstories in superhero comics — they almost made a movie entirely about it. He was once a young Jewish boy when Nazi Germany invaded Poland. Captured and dehumanized, he suffered at concentration camp Auschwitz like so many of his people. He survived but it convinced him that hatred is as natural to men as breathing, and so he fights to ensure the prosperity of mutantkind. This backstory was not part of Magneto's original conception (Chris Claremont added it in 1981's "Uncanny X-Men" #150), but you'll be hard-pressed to find a writer who hasn't embraced it since.

"X-Men '97" certainly has. In episode 2, "Mutant Liberation Begins," when Magneto is tried before the United Nations, he recalls how he was first put on his path when his people were slaughtered because "they called God by a different name." Episode 8, part one of the finale "Tolerance is Extinction," takes it to another level. As revealed in the last episode, "Bright Eyes," Magneto is a captive of Bastion and Operation: Zero Tolerance. By this episode, he's stripped nearly naked and strung up. ("X-Men" comics have always gotten a lot of mileage out of Saint Andrew's Crosses, a common BDSM toy, being in an X-shape.)

Dr. Valerie Cooper, who previously presented as the X-Men's ally but revealed now as an Operation: Zero Tolerance member, visits Magneto. She sees a number inked on his wrist: 214782. Auschwitz inmates were tattooed with identification numbers, just another way the Nazis stripped them of dignity. Magneto's tattoo has been a character feature for decades, representing how his suffering is burnt into his skin and soul. He can't forget what happened to him because, whenever he feels the blood on his own hands, the reminder of why he's dirtied them is right there to see.

Magneto, Holocaust Survivor

To hammer in the comparison, Cooper (who ultimately has an attack of conscience and frees Magneto) compares Mister Sinister to Nazi doctor Josef Mengele, one of Auschwitz's worst butchers. Mengele tragically escaped to South America and died unpunished, inspiring conspiracy thriller "The Boys From Brazil" starring Gregory Peck. Sinister dislikes the comparison only because Mengele thought too small.

"X-Men '97" being so blatant is refreshing because, if you don't remember, Magneto's past is one area where the 1992 "X-Men" cartoon hedged and kept things vague. Magneto is introduced in episodes 3-4, "Enter Magneto" and "Deadly Reunions." The former episode has a flashback condensing "Uncanny X-Men" #161 (by Claremont and Dave Cockrum). In that comic, Professor X and Magneto meet in Israel when they're both working at a hospital to help Holocaust survivors. They learn each other are mutants when Nazi lost-causers (led by HYDRA leader Baron Wolfgang Von Strucker) attack and abduct their friend Gabrielle Haller.

In the episode, when Professor X tells Jubilee how he met Magneto, he just says they met after "a war." The setting is moved from Israel to Magneto's unnamed home country and the Nazis replaced with a generic invading army. In "Deadly Reunions," Xavier cows Magneto by telepathically forcing him to relive memories of his family's death; tellingly, the episode uses imagery of a wartorn town, not say, young Magneto being torn from his parents at a concentration camp like in the opening of the first (and at the time, still-to-come) "X-Men" movie. (This is the rare scene that the "X-Men" movies' timeline kept consistent, as seen in shot-for-shot remake in "X-Men: First Class.")

The Testament of Magneto is Never Again

The essential beats of Magneto's origin are the same in the 1992 "X-Men" cartoon. When Magneto confronts anti-mutant Senator Robert Kelly in the season 1 finale, "The Final Decision," he recounts: "When I was a boy, I saw men executed — women and children! Each night I swore to myself... 'Never again.'" That word choice is pointed, and educated adult viewers can read between the lines.

In "Previously on X-Men: The Making of an Animated Series," author and series writer Eric Lewald admits they "updated" Magneto's origin from the Holocaust. This phrasing implies that they thought the timeline wouldn't line up for Magneto to be in his peak supervillain years (if he was born in, say, 1935, he'd be 57 in 1992). Or maybe it was just more of the stringent censorship that superhero cartoons often suffered. If so, I think it does children a disservice to water this subject down. "X-Men" is an unusual source for Holocaust education, but the show's message is all about tolerance, and showing what happens when it doesn't prevail reinforces that lesson.

Not explicitly drawing on real history for Magneto's origin robs it of power. "Magneto is/was right" rings harder because his radicalization stems from a real act of human evil. Not just any act, either, but one of the most monstrous in our history, carried out in the name of bigotry and dehumanization of a minority group. Claremont also wasn't being exploitative; he's Jewish himself and was inspired in part by the time he spent living among Holocaust survivors in Israel as a young man.

The 2008 comic "Magneto: Testament" by Greg Pak and Carmine Di Giandomenico depicted Magneto's childhood in greater depth than ever before and finally gave him a Jewish birth name: Max Eisenhardt. "X-Men '97" is being similarly restorative with this writer's favorite mutant anti-hero.

"X-Men '97" is streaming on Disney+.