One Twilight Zone Episode Inspired A Horror Classic – And One Very Annoyed Writer

The last 70 years of science fiction, horror, and fantasy wouldn't just look remarkably different without the works of Richard Matheson, they'd be comparatively barren. Okay, this is a touch hyperbolic, but only a touch! Yes, we'd still have the transporting, thought-provoking works of maestros like Ray Bradbury, Isaac Asimov, Philip K. Dick, and so many others, but could you imagine living in a world sans such essential tales as "The Incredible Shrinking Man," "I Am Legend," "Hell House," and dozens upon dozens of eerily prescient (or just straight up horrifying) short stories? And these weren't just spellbinding reads. They formed the basis for many memorable movies, and, perhaps most influentially, 16 unforgettable episodes of "The Twilight Zone."

Countless writers and filmmakers have cited Matheson as crucial to their development as genre storytellers (Stephen King considers "Hell House" to be "the scariest haunted house novel ever written"), and you could argue that Steven Spielberg's career might've taken a considerably different path had he not adapted the author's short story "Duel" as a made-for-TV movie in 1971. The relentlessly terrifying film about a mild-mannered salesman being terrorized by a tanker truck across a Mojave Desert highway was such a ratings success that Universal Pictures commissioned Spielberg to shoot an additional 16 minutes of footage so it could release the film theatrically.

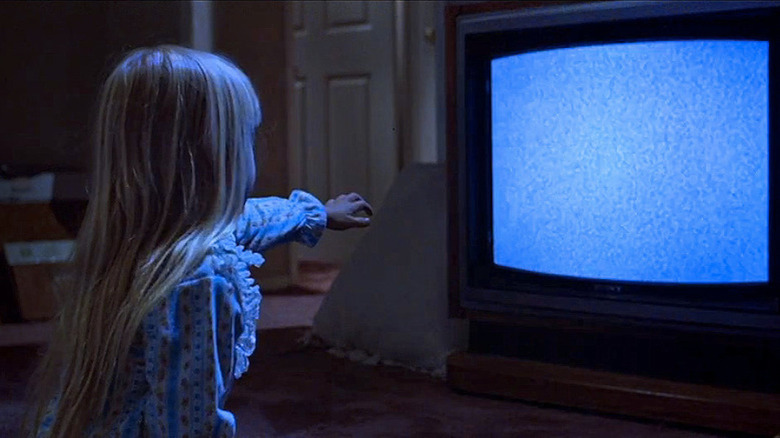

"Duel" was the film that announced Spielberg as, if nothing else, a first-rate conjurer of suspense. Matheson wrote the fiendishly efficient screenplay as well, so you'd think the young filmmaker might want to re-team with the author somewhere down the line — and, 10 years later, he did. Kind of. He just failed to give the author proper credit for inspiring a little blockbuster horror flick called "Poltergeist."

The inexplicable disappearance of a little girl in her own house

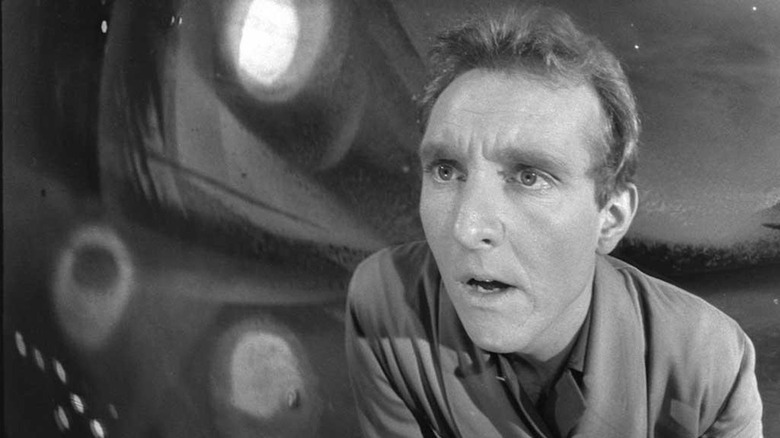

"Little Girl Lost" may not be a top 10 "Twilight Zone" episode, but conceptually it's one of the series' most ambitious. Chris and Ruth Miller (played by Robert Sampson and Sarah Marshall) are a married couple awakened by crying from their young daughter Tina (Tracy Stratford). They assume she's having a nightmare and needs comforting, but upon entering her room, Chris discovers she's not in her bed. They continue to hear her eerily disembodied cries as they search her room, but, unnervingly, she's nowhere to be found. When Chris can't reason out her whereabouts, he phones his physicist friend Bill (Charles Aldman) for help.

It's at this moment Chris lets their yapping dog inside the house. When he bolts straight under the bed and disappears, the Millers' unease skyrockets to sheer terror.

Bill discovers there's a parallel dimension that exists behind a small swath of the wall in Tina's room. He explains that they cannot enter this realm to search for Tina because they would only become lost as well. Fortunately, the dog is able to locate Tina, so the trio begs for the young girl to follow the mutt. She's afraid to do so, which causes Chris to panic and reach inside the dimension. Caught halfway between our world and whatever exists beyond that bedroom wall, he manages to rescue Tina (and the dog) just before the portal closes.

In his closing narration, Serling can offer no tangible explanation for the Millers' bizarre ordeal. All he can do is advise that we all exhibit "a little more respect for and uncertainty about the mechanisms of The Twilight Zone."

It's hardly a one-to-one comparison, but would "Poltergeist" exist without "Little Girl Lost"?

Poltergeist actually borrowed from more than one Matheson story

Like so many of Matheson's best stories, "Little Girl Lost" places a sui generis spin on a familiar situation or common theme. In this case, it's every parent's worst nightmare: a missing child. Matheson's clever spin is to place Tina agonizingly out of reach; Chris and Ruth can hear her, but they cannot rescue her.

Spielberg gets sole story credit for "Poltergeist," wherein the Freeling family loses their daughter to an explicitly spiritual dimension, and on first blush, you could argue that the parapsychology angle is different enough to separate his idea from Matheson's. But here's the thing: the idea of parapsychologists using modern technology to investigate a haunted house is directly lifted from "Hell House." And while several writers prior to Matheson experimented with tangible, pseudo-scientific explanations of the paranormal, none went to such specific lengths as he did with "Hell House."

So here you have Spielberg, like Chris, stuck between the narrative realms: the multi-dimensional terror of "Little Girl Lost" and the parapsychological dread of "Hell House." "Poltergeist" is one big Matheson homage!

So how did Matheson feel about not receiving a story credit for "Poltergeist"?

'He must have felt guilty or something'

I asked Matheson about this in 2011 when he granted a few interviews to promote "Real Steel" (which was more loosely based on his story "Steel" than "Poltergeist" was on the aforementioned tales). At first, he laughed that he never got credit for it, and was, I would say, thornily diplomatic. "They sort of used that idea [for 'Little Girl Lost'], and made their own concept of it."

I returned to the subject when I asked how he felt about Spielberg producing "Real Steel" all these years after "Poltergeist." His response:

"Well, I don't even know if using 'Little Girl Lost,' and kind of taking some of it for 'Poltergeist' [...] God, he must have felt guilty or something. Because he hired me as the creative consultant on 'Amazing Stories,' and I didn't do too well on that. [Laughs] I rejected two of his stories. I'm not too political when it comes to this kind of thing. If I don't like something, I don't like it, I don't care who did it."

Matheson did clarify that he always had "an amiable relationship" with Spielberg, and revealed that he'd tried to get the director to do an official adaptation of his 2011 novel "Other Kingdoms." Spielberg declined. Then again, Matheson had turned down Spielberg at least once before, most notably when the filmmaker invited him to write "Close Encounters of the Third Kind" ("At the time I just equated it with a spaceship story," he said).

Ultimately, their creative collaboration worked out fairly well. I just wish Spielberg would be above board about "Poltergeist" as an affectionate Matheson tribute (even if he didn't explicitly set out to make one) — because it's a terrific film, and he should be proud that he did the maestro justice.