An Oral History Of Spider-Man 2's Train Scene, One Of The Best Action Scenes In Superhero Cinema

The biggest set piece in the most recent live-action Spider-Man film, 2021's "Spider-Man: No Way Home," involves, through a series of multiversal shenanigans, Tom Holland's friendly neighborhood web-slinger teaming up with two other Spider-Men to fight Electro, Sandman, and the Lizard on the Statue of Liberty.

The biggest set piece in 2004's "Spider-Man 2" involves Tobey Maguire's Spider-Man trying to stop a train full of innocent passengers from crashing.

By comparison, the train scene may seem almost quaint, but director Sam Raimi used it as an opportunity to combine then-state-of-the-art action filmmaking with genuine humanity and pathos, resulting in a cocktail that dozens of superhero films have been unable to fully replicate in the 20 years since. You remember the scene: As Spider-Man and Doctor Octopus (aka "Doc Ock") are fighting on a New York City skyscraper, they fall onto an elevated train zooming through the city and continue their brawl atop the train cars. Naturally, Doc Ock plays dirty by endangering the lives of the passengers; he puts the train on a speeding crash course to oblivion, and it's up to Spider-Man to come up with a way to prevent catastrophe.

It has practically everything you could want in a Spidey action scene: thrilling choreography that feels motivated by character, spectacular stunt work, excellent visual effects, and enough of a connection to regular, everyday people who populate that world to make it feel personal and tactile. With the benefit of 20 years of hindsight, this approach is starkly different than many other superhero movie action beats that would come after it, many of which balloon into scenes so massive that they feel impossible to relate to.

To celebrate this year's 20th anniversary of "Spider-Man 2," a film still widely recognized as one of the best comic book movies ever made, I spoke with several people who were involved in the creation and execution of its best set piece to find out how it all came together and instantly webbed its way into history as a high point for superhero cinema.

Pre-production: 'An ambitious endeavor'

Sam Raimi's approach to making movies differs from some of his contemporaries, so planning for this gargantuan action scene was a multi-disciplinary collaboration. And since much of the scene involved train cars hurtling through the streets, extra attention to detail was paid to ensure everything looked as realistic as possible ... within reason.

Scott Stokdyk, production visual effects supervisor: It was a pretty extensive process in pre-production. Sam loves multiple storyboard artists and he loves doing pre-vis [pre-visualizations], too, and he brings his editor in and he cuts it all together multiple times. He brings the stunt people in, there are good second unit directors he works with, and it's like, "Let's work on this action beat." It's this involved process. I actually brought in a little prop today. [Holds up a model of a subway car that's about a foot long.] I kept this from that movie. It's very low-tech, but the art department will make a little foam version and you just have all these discussions on a table around this. "We're going to have a camera here, we're going to do this." So, it was such a mixture of high and low-tech drawings and discussions, and it was a fun process.

John Dykstra, production visual effects designer: We decided to shoot it blue screen, because obviously you had to have something outside the windows. Then we needed the live-action portion of the train doing things. So Sam gave me the opportunity to do second unit, go to Chicago, and shoot the train stuff. So I took a crew and six cameras, and we went to Chicago, and they gave us a flat car that we put cameras on. They gave us several train cars and our own engine and all of the personnel that went with that. We had our own train, and of course, it was Chicago, so it was really cold. We had all the windows out and the doors open so we could shoot the cameras, so it was quite an experience. We are shooting and, at the same time, the train system is in operation. So it was a constant interface between our picture train and the real trains that were on the tracks. We had to keep people from trying to get on the train when we came to a station, and of course they had to tell everybody that the train might just go through the station, so people didn't get upset about, "Hey, wait a minute, you didn't stop!" We braved the cold, and it was bitter for some of those guys. Trying to load a camera, you had to load it barehanded, and it was cold enough that everybody was wearing gloves.

It was it an ambitious endeavor, but we were successful, and these were the days of shooting film. So we had different format cameras. I don't think we shot IMAX, but we had VistaVision cameras and forklift cameras and 65 millimeter cameras, and the attendant crews. One car had four cameras in it, so there's four camera crews, with the camera assistants and the loaders and everybody all hovered around their camera. Then we talked to the dispatcher, and we'd be on a siding and the train would go by, and then they'd give us approval to go out on a particular section train, and we had to roll all the cameras, get everything going. That provided us with the plates for the material outside the windows, for both the sequences from inside the car and the wider shots where we were going to put a computer generated train in [...] Then, we also shot the train itself in a variety of situations. Anybody who lives in New York knows that the trains in New York don't do some of the things that our Chicago trains did, but it was effective, and I don't remember any complaints.

Scott Stokdyk, production visual effects supervisor: Every Sam Raimi movie I've worked on, there's always a free-flowing change and morphing of ideas. Sam's a person who likes to keep working on something over and over and over again like a sculpture and until, basically, they take it away from him, until we run out of time. I remember once seeing storyboards for "The Matrix" versus the final movie, and it's almost one-to-one, right? Sam's definitely not that way, and that's kind of the challenge and the fun of it is he does a little something in the edit and it just magically makes it better. And you're like, "Wow, that's cool."

Bob Murawski, editor: It was the first scene I started on, and I think it was the last scene we finished on the movie [...] Sam brought me in a few months before they started shooting to work on the train scene. I think that was the first big set piece that they had started developing. It was that, and the operating room scene with Doc Ock [...] But the train scene, the urgency for bringing me on for that one was he'd had it storyboarded. [Storyboard artist Jeff Lynch] and Sam had been working together for a couple of months, figuring out the scene. Storyboards are also used for things like budgeting, so they broke down the budget of the scene as it was boarded, and they were way over budget. I think they had something like $12 million for the scene, and I think as boarded, it was coming in at $18 or $19 million. So it was probably like 50% over, in terms of what was in the budget.

So Sam brought me in, saying, "Look, I just want you to put the scene together from the boards, whatever animatics" — which are sort of the animated version of storyboards — "and some small amount of pre-vis." And he said, "Just cut the scene together, and put some music and sound effects into it. And then figure out how we can cut it down and get it within budget."

So I just basically put it together, and looked for places where things maybe seemed repetitive, or things that we could get rid of. I was working with Jeff and the animatic guys, the guys who were actually doing animated versions of the storyboards, a guy named Anthony Zierhut, and another guy named Brad Morris. I figured out places where we could remove material if things seemed maybe a little redundant, or maybe they were good, but things that were clearly we couldn't afford. And then I would work with those guys and we would come up with little bridging pieces, to take the place of something that had been cut out — maybe one or two shots that could bridge a couple of little action pieces within that, to keep the flow going.

After a few weeks of that, I was able to come up with something, working with them and working with Sam, that sort of got the scene within budget, which was a good first step.

Alfred Molina, actor ("Otto Octavius/Doc Ock"): The first time [Sam] took me through it, I actually said to him, "I feel like I'm watching the movie." Because I'd been used to seeing storyboards. I remember the first time I saw a storyboard was on "Raiders [of the Lost Ark]," and the storyboards were like little captions from a comic. They were quite exciting, but it was like looking at a comic book. But the pre-vis, because it was all movement, it really was like watching the movie. And I thought, "Wow, this is going to look amazing." So I remember going into it, very excited, very nervous as well, because I didn't want to make a fool of myself.

Setting up: 'If we were doing this today, there'd be LED walls'

While much of the live-action exterior footage was captured in Chicago doubling for New York City, the filmmakers quickly realized they weren't going to be able to shoot everything they needed for the scene in uncontrolled outdoor environments.

Scott Stokdyk, production visual effects supervisor: I was always most worried about the all-CG shots. To his credit, John Dykstra got us to get plates of moving backgrounds from Chicago, the "L" train there, just putting a bunch of cameras on trains and running them around, shooting a lot of photography in New York, more static camera stuff that we used.

John Dykstra, production visual effects designer: It was one of several epic sequences. That was the early days of superhero films, so every 10 minutes, there had to be another action sequence that gave people some adrenaline. It was ambitious. The idea of access to trains, the primary criteria initially was going, "Okay, so we can't really get operating trains and shoot on them." You can't go take live actors on operating trains, and it's a weird deal, because although we were spending time on the roof of the train, a lot of the live-action stuff had to be done inside and it had to be integrated. We went through the whole process, went to New York, looked at the trains there, and checked with them about availability and being able to shoot.

Live-action shooting in New York was always complex, and it was difficult to arrange. So they pursued talking to people in Chicago, where the "L" and the downtown loop is sort of a very established environment, and very similar in terms of architecture, the nature of the trains, the elevation part of it, and all of that. So we decided to shoot Chicago for New York. Then it was the issue of, "Okay, where does the division occur between what is shot live-action with actors in or on a train?" It was pretty quickly determined that it wasn't going to be practical to mount a production with a level of complexity that we wanted, even for the live-action portions that took place in the interior of the train.

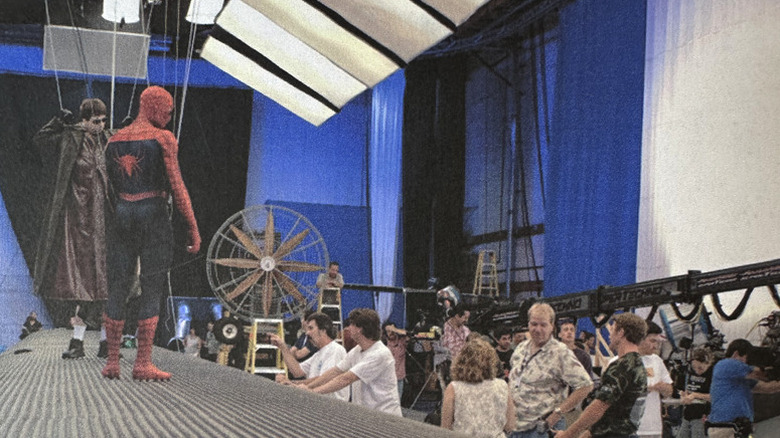

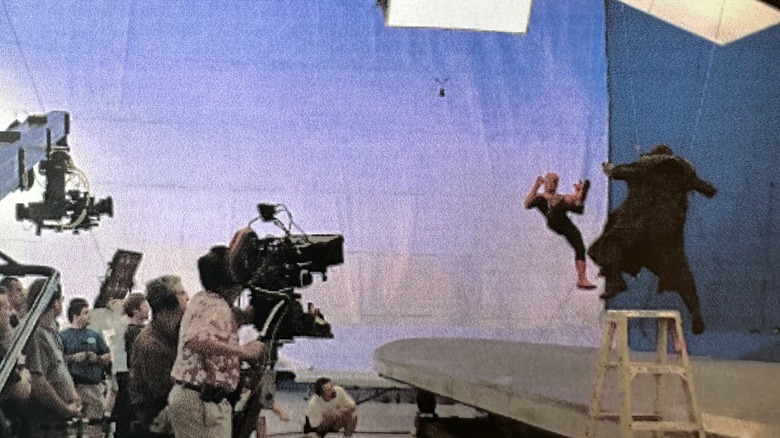

So they decided they'd get train cars and actually put them on a stage, which is no [easy] feat. They're big things. So they mounted train cars, got them on a section of track on a stage, and prepared to do the live-action conversation, dialogue stuff that went on inside the train.

Scott Stokdyk, production visual effects supervisor: It was actually very, very, very difficult to work on that sequence. For most of working on it, I was just in the weeds and struggling over the shots. There were a lot of difficult shots in that scene and I look back on it and some of them I wish I could work a little bit longer on. Some of the blue screens, you're kind of like, "Ah, now we probably would change the exposure or the color temperature." You'd do a couple little things to integrate it more. But at the time, it was like every challenge is like, okay, we have this environment and we've got to piece together New York and Chicago and CG buildings and we've got to have digital doubles. And I was just so struggling shot by shot and then at one point, almost near the end, and I was so frustrated and we just sat down in editorial and we watched the whole sequence with sound and everything and I'm like, "Oh, I get it! This is good. It's actually good!"

John Dykstra, production visual effects designer: Editorial had to sort out what forward-looking stuff went with what side-looking stuff, [and] went with what aft-looking stuff, and where it was in the sequence.

Alfred Molina, actor ("Otto Octavius/Doc Ock"): All this stuff that you see in the finished product, the train rushing through that canyon of apartment buildings and so on, you're not aware of any of that. So you're acting in a kind of vacuum, in a way. You are relying on other people's skills. You're relying on their timing, in a way, to pull you, because they're working to a very specific timeframe, because this has to happen before we reach this point in the story, before we reach that. So they were constantly referring to [the pre-vis].

Scott Stokdyk, production visual effects supervisor: We couldn't afford or have time to do that many all-digital shots. So, it's probably — and my memory's going to not serve me well here — but probably less than 10% [of the train scene was] all digital, maybe even 5%. It's like very sparing, and the good thing about a train sequence is once you're inside, it's basically it's all actors and all just filling in blue screen. If we were doing this today, there'd be LED walls and stuff. If you could get that together, you'd probably try to do that because it's really good for lighting and reflections. Bill Pope was one of my favorite [directors of photography] of all time. He was clever, and I think John Dykstra tested projecting stuff onto screens and Bill Pope had a moving lighting rig, so they were basically kind of anticipating that technology, but there were a couple pieces that weren't in place where you could really do that.

Bob Murawski, editor: I worked on [that scene] for several months before we started shooting. And then we continued to shoot, all of us for it, all through production. Sam shot a lot of it first, then with the actors. Dykstra shot some of it. Dan Bradley, who's a stunt coordinator, shot a lot of it. He was the second unit director. Jim Fletch, who was the main storyboard guy, was also one of the second unit directors. So he shot a lot of the elements as well. So throughout the entire production of the movie, and throughout the entire post-process, the scene was constantly evolving and becoming more and more finished.

Stunt fights: 'I rung my bell'

In 2024, most of the fight between Spider-Man and Doc Ock would likely have been made using digital body doubles. But back in 2003, as filming was taking place, Raimi relied heavily on his stunt team to contribute their brand of movie magic.

John Dykstra, production visual effects designer: There was a lot of stunt work that was really exceptional. The stunt people did a terrific job on that.

Brad Martin, stunt double ("Spider-Man"): That whole sequence was designed to the point where it almost didn't allow for any room for interpretation. So Sam Raimi and all the guys got together and they made the sequence with the visual effects guys, and then Dan Bradley and the second unit, they would try to match the animatic per frame. So if it was a couple frames off, and Dan Bradley directed something, he brought it over to the other stage to Sam, and Sam would compare it to the other one and go, "Hey, this is a couple frames too long. Go redo it." It's like, "Really? We're shooting live-action trying to match animatics." Yeah, they were nitpicky about it. They were super specific.

Ray Lykins, stunt double ("Doc Ock"): I was the only double for Doc Ock, so if I wasn't on any of the three sound stages rehearsing, filming, or trying something exotic [where] they were trying to invent something, that's all I did. But our thing was to get it from real stunts. Every day, we'd go, "Okay, we've got to keep the stunts live." Because if we couldn't get it — we'd rehearse it and the guys are figuring out the rigging and this and that and we get everything going, and they'd film it and then they'll run to Sam Raimi on a different soundstage and say, "What do you think? What do you like?" And then that would either get the thumbs up or the thumbs down, because we wanted everything live instead of going to CGI. So that whole movie, every day was just boom, boom, boom, boom, let's get this real.

Brad Martin, stunt double ("Spider-Man"): I loved it. I was a comic book freak, a Marvel fan, loved Spider-Man my whole life, and always wanted to be Spider-Man [...] Tobey is not Spider-Man, and Tobey needs to become Spider-Man. So we were given comic book photos or stills or cells, whatever, to try to copy poses and learn how to pose and move like Spider-Man. But even as far as the doubles go, Tobey's 5'7", I don't know what he weighs, but I'm 5'11", 180 [pounds]. So they wanted Spider-Man to be bigger and more imposing, and we all wore muscle suits as well. So we didn't look like him. And Tobey's not necessarily that athletic of a guy ... we would never move like him. He would do his best to try to move like Spider-Man, I would say.

Bob Murawski, editor: For some reason, one of the toughest VFX shots was to get the burning mask to look real in the scene where Peter pulls off the mask. That was one of the last shots to be completed. Sam knows that it's almost impossible to get any emotion from a masked character, so always tries to get the mask off as quickly as possible in these important action scenes, even if it's just partial, like the big fight with Goblin at the end of "Spidey 1." And because Tobey is such an expressive actor, it always pays off.

Scott Stokdyk, production visual effects supervisor: But there's still some shots where you couldn't get a stunt person to do it, even on a stage in a controlled environment. Spider-Man, you could put a lot of great specific stunt people in the suit, like Cirque du Soleil performers or different stunt people for different type of actions ... there was a wide variety of backgrounds that the stunt people came from, and I never knew why they were cast for each stunt, but it was kind of fun to see.

Brad Martin, stunt double ("Spider-Man"): There was Chris Daniels, Johnny Nguyen, Zach Hudson, and I think there might've been one other guy that doubled Spider-Man. So we were all the doubles and we'd just be bouncing all over the place. So with the train sequence, I did all the stuff on the side of the wall, along there, and I did a couple of things on the top, like when he grabs the controller and it burns his eyes.

Ray Lykins, stunt double ("Doc Ock"): There were a bunch of different Spider-Man doubles because the guys were getting tweaked here and there. So I know the guy, Brad Martin, was the actual double for that [moment] when [Spider-Man] comes crashing through. I remember that specifically because we rehearsed that all together.

Brad Martin, stunt double ("Spider-Man"): The one gag that I did — I mean, it's one that I'll never forget — is when I got drove through the subway door, the train, and hit the other side right there. That was one of the bigger hits I've taken in scenes. I rung my bell. It could have rendered me unconscious for a moment, possibly. I just remember my only job was to grab the bar when they pull me back. So hit the door, pull me back, and grab the bar. So that was all I was thinking. It was like it was going to hurt, [mimics sound of crashing through the door], I just got my arms out there and it was enough for the shot, but I definitely was not in a very conscious state of mind [...] I only went through once. But that's unusual. We call them "one take wonders," once in a while you get a one take, and usually with a special effects gag like that, you do two, sometimes three. So it was surprising, but [that] was only one.

Wire work: 'I'd never worked with a harness before'

A CG Spider-Man can easily swing through the streets of New York, but the human stunt performers and actors, including Alfred Molina and even Aunt May actress Rosemary Harris, found themselves in harnesses hooked up to wire rigs, dangling inside the Sony soundstages in Culver City.

Alfred Molina, actor ("Otto Octavius/Doc Ock"): I was quite impressed at one point, where for all the technology — and there was a great deal of it — when it came to me flying, it was down to four hefty guys at the end of a rope just pulling, and me going "Whoa!" up in the air. And then you go, this is what keeps the whole thing terribly human. It's not like a machine doing it. It's four guys on a rope, and they've working hard because they've got to time it perfectly [...] When you're being lifted by the wires, and then you're landing, you've got to land as if you are in complete control. You've got to land as if it's the most natural thing in the world. And there's always a few stumbles, and it's not always one's fault. Sometimes the ropes get tangled or the wires don't behave. And it took a while.

Ray Lykins, stunt double ("Doc Ock"): I did a lot more wire work too, for me. I mean, I've done ratchets where you cable off of things and stuff like that, but [on this movie], me physically being in the air or fighting, we'd get tied up and stuff. We're 90 feet in the air doing flips, trying to undo the wires ... I turn and look and here comes one of the doubles, all I see is bottom of the feet coming right at me and then bam, kicking and fighting. You get tangled up when you're just trying to figure it out.

Dan Bradley, second unit director: Frankly, the level of wire work that happens today is I think less than what we were achieving back then, because we were driven to make it feel absolutely real. Me and my guys invented sh*t that wasn't done before, and I have people write me letters and talk about a certain wire wrap and things ... so a lot of that stuff has been adopted kind of around the world.

Alfred Molina, actor ("Otto Octavius/Doc Ock"): I do remember at one point that the harness — I wasn't used to that. I'd never worked with a harness before. They were using this harness, it was basically your whole body. It starts up here [points at his chest], and then the harness goes down and it ends somewhere just above your knees. So your whole body is encased, obviously for safety reasons and so on. But it was a very odd feeling, and I can remember turning around to one of the technicians at one point and saying, "It's chafing me a little bit down here. I'm feeling a little sore." And he turned around and said, "Well, Rosemary Harris has been in one for the last two weeks. She hasn't complained once." [laughs] I felt very chastened after that. I thought, "Well, if Ms. Harris isn't complaining, then I should keep my mouth shut."

Alfred Molina: 'I will never take a day away from a stunt guy'

From all accounts, Alfred Molina was an absolute pro, despite never having been in a movie as technically complicated as this one.

John Dykstra, production visual effects supervisor: I think that Sam did a terrific job. His Spider-Man movies, for me, seemed to be a great capturing of the essence of the character. Not that the subsequent ones weren't good, but I think for an origin story, it was really great. His choices of performers, with Tobey and Alfred and the people who were essential to it, I think, were really inspired.

Alfred Molina, actor ("Otto Octavius/Doc Ock"): The overriding memory I've got, really, was, it was just such great fun. I'd never done anything like this in my life. I'd never worked on this kind of movie before, so all the technology [...] then was cutting edge, but I still had the arms attached. The tentacles were still attached, so there were puppeteers in blue suits working them and stuff. So it was kind of cumbersome and the movement was — we were kind of slow.

Ray Lykins, stunt double ("Doc Ock"): Alfred's a great actor. A lot of people don't realize he's classically trained. He's a full-on actor, not a guy just winging it and trying it. Super nice guy, nicest guy ever. When I met him, he said, "Hey Ray, you know what?" We met in the wardrobe fitting and he goes, "I will never take a day away from a stunt guy." And I go, "Perfect. That's perfect. We're going to have a great time." And sure enough, he held that true. It was like every time it'd be anything near action, he's like, "Where's Ray at? Where's Ray?"

Brad Martin, stunt double ("Spider-Man"): I fought Alfred, and he's super cool. We hung out a little bit. He's a gentleman, super smart dude. Really, really, really cool. And just a professional all the way around. Tobey stays in his trailer a lot, since when he's Spider-Man, his hood's on. He wasn't generally there when I was around.

Alfred Molina, actor ("Otto Octavius/Doc Ock"): I remember there was another day when Rosemary Harris and I were suspended up in midair. We were shooting the sequence where I'm carrying her. I've stolen her, and we're going up the skyscraper. And we shot it in all kinds of ways. We shot it where the skyscraper was flat, and we were working horizontally. We had a sequence where it was vertical, and I think the shot was her when she whacks me with the umbrella. And so we were up quite a good, I don't know, 20, 40 feet up in the air in our harnesses, and we're doing it. And then suddenly everything stopped, and everyone on the deck, they've all gone to monitors, and they're looking at monitors and talking and talking, and we're up there for quite some time. And then I hear one of the guys on the floor say, "We'll only be a minute, if you don't mind staying up there." Because bringing us down and taking us up always took time. So we both went, "Yeah, this isn't exactly uncomfortable. We'll stay up here."

So we're up there, and we've been up there for quite some time. Rosemary and I, we actually began to run out of small talk, and then it was a hot day and someone opened the dock doors of the soundstage, and we caught this breeze. And so the two of us are suspended, and we start floating. The breeze has caught us, and we're like floating like this. And out of the silence, as we're floating like this, Rosemary says, "I'm classically trained, you know." [laughs] I've never forgotten that.

Ray Lykins, stunt double ("Doc Ock"): They were filming me head-on and he came walking in, joking because he always jokes around. He goes, "Why am I doubling Ray now?" Because I shot it, and then they're going, "Okay, well Ray did this and Ray did that." He goes, "Wait a second. Who's Doc Ock around here?" He was joking. That's how well we got along and how much I looked like it to where they were shooting me head-on without [trying to hide my face].

Alfred Molina, actor ("Otto Octavius/Doc Ock"): I remember there was a moment when Spidey hits me or sends me reeling back, and I had to fly back, and the wires are pulling me back. And there was this sensation of, when we first did it, I just remember — I think we were working with the [second] unit director, I'm not sure if I was working with Sam on this sequence — but he kept saying what I was doing was, because I wasn't used to it, the first couple of takes, I was giggling a little bit, because the physical sensation of suddenly being pulled back was making me go, "Whoa!" It was making me giggle. So I had to conquer that.

Ray Lykins, stunt double ("Doc Ock"): He's the funniest guy, you could always know where he's at because you could hear him on the set because he's laughing, always laughing, talking. He'll talk to anybody — grips, it doesn't matter. He has no ego, none of that. He's just talking and laughing with everybody, always. Super nice. He knew right away he wasn't going to do any stunts at all, and that worked out for me and everything else too.

Alfred Molina, actor ("Otto Octavius/Doc Ock"): I remember once I had to do a reaction to a punch or a hit, I had to literally go "Ah!" [acts as if he was just punched in the face] or something like that. We must have done it, I don't know, 25 times. And I remember after a while thinking, "I must be the sh*ttiest actor in the world. I can't even get this right." And then after about 10 or 12 takes, I said, "I'm sorry, am I doing something wrong? I don't quite understand." And he said, "Oh, it's not you. It's nothing to do with you." And I suddenly realized nobody was looking at me doing that. Nobody was going, "I don't believe that reaction." They were all watching it on a computer on top of some kind of pre-vis, and it was all having to time in with a whole bunch of other elements. So it was less to do with me and more to do with how the overall thing's going to look in terms of lighting and so on. And that's when the penny dropped, and I realized, "Ah, that's it. What I'm doing is just a small part of a much, much bigger series of things." And as soon as you embrace that fact, that's when you can really start enjoying the process. It's a great lesson to learn that, when you're doing something over and over again, it's not necessarily about you. It's about a whole bunch of other things.

Give and take: 'There's a lot of trading going on'

Dan Bradley, second unit director: We were pretty excited about how things were turning out, because the sequence was almost entirely done on second unit. I mean, even the Peter Parker being hoisted above the passenger's heads in that pose and being carried into the [train] car, that was all in second unit. So, there was a lot of responsibility and trust that Sam gave to us, and certainly he saw everything we did and made sure he was happy with it before we moved on, but not often do you get that opportunity.

Bob Murawski, editor: When Spidey 2 was a success, the studio said, "Hey, we want to do an extended version." They were calling it "Spider-Man 2.1." And [they asked], "What do you guys want to put back in?" And Sam actually didn't feel like he really wanted to put anything back in, but I went through some of the cuts that we had made in the train sequence, and we put a couple of the fight beats back in [...] it was just a little bonus for the fans, and another way for the studio to fleece the kids for an extra couple bucks to buy the movie again. [laughs]

Some of the [cut moments] really weren't working as well, in terms of the stunt work or the CGI. We didn't have a chance to develop the CGI [the first time around], so some of the cuts we made because we didn't really have time for the shots to become refined enough. But then when they okayed that version, we were able to go back in and finish those shots.

Even though there was this cut down version, there were still budgetary problems along the way, where sometimes, in order for another scene to be made better, we would have to make cuts within the train scene. We would say, "Well, if we cut these one or two shots in the train scene, then maybe we can afford these shots elsewhere in the movie." I think there were some things in the operating room scene that we were able to do. There's always this give and take on these effects movies, where there's a lot of trading going on everywhere along the way, where maybe one super expensive shot might pay for five or six shots that are less expensive, but more important dramatically.

Meet the passengers: 'That's not how you hold a baby'

The actors who played the train passengers may not have had a ton of lines, but they were crucial to the success of this scene and a huge part of the reason why it's so fondly remembered today.

Peter Allas, "Train Passenger": I would say that the most important thing is feeling like you're really on the subway. And that was, part of it was the soundstage, the set crew, the way they kept us on it. There wasn't a lot of release time and I think that was very smart because you feel like you're in a New York subway, which I've spent many a time stuck on a train in New York for other reasons. I had that to draw from, from personal experience, but they were smart. It was hot. And there was times where they had those big cones that blew air in because you don't want anyone to faint. But you want that feeling, too, to help create the realism that Sam Raimi brings to the movie in terms of the way he shot it, the depiction of New York City. To me, being a New Yorker, wow. It's hard not to feel it.

Brianna Brown, "Train Passenger": I remember it was the first time I've been into a sound studio that was as ginormous. It was huge, and there were so many extras and so many people playing people riding on the train, and so many actors hired for just those small close-up moments.

Peter Allas, "Train Passenger": I was supposed to be playing Peter Parker's boss, and something happened, I couldn't do it, and I vaguely remember them saying, "You have to be a local hire out in New York." And I said, "I live in L.A. now and I'm not going to do all that. That's too much work, because I got a project in L.A." So I ended up passing on this movie initially, and then I got a phone call from [the casting directors]. "They want you." I said, "This movie's done already!" They said, "No, it's not." And I was living in Marina del Rey and I went to Culver City — it was an easy drive to Sony Studios for me. The only time in my whole career I was able to go home for lunch was filming this movie ... I typically play mafia guys or cops, and they told my agent, "Okay, you're cast. You're filming in a week." I'm like, "Whoa, okay." "Just these couple days." It ended up being three and a half weeks.

Brianna Brown, "Train Passenger": It was really fun getting to be with all of these — a lot of them were very much working actors in these smaller parts in this big movie sequence. I also remember at one point Sam Raimi telling me — we were on a break and I was holding the doll just by its leg. And he's like, "That's not how you hold a baby." [laughs] And I said, "Well, the camera's not rolling!" because we'd been pretending for hours and even a couple of days. I think he got a kick out of that.

Peter Allas, "Train Passenger": Working with [Sam], he was so specific with everything, even to put me in a Mets hat, which killed me because I'm not a Mets fan, but that's okay. [laughs] I'm a Yankee and Giants man. Every little detail: "Get him a vest. I want him to look like this." So the wardrobe was great.

I reached out to Phil LaMarr, who had an uncredited role in the movie as one of the train passengers. Mr. LaMarr was unavailable to participate, but I was pointed to an interview he did with the Blerd's Eyeview podcast where he spoke about his experience on the film. When you see any quotes from him in this article, that podcast appearance is where they came from.

Phil LaMarr, "Train Passenger" (uncredited): I had auditioned for a regular part on the movie, trying to be the dude who's in the elevator next to Peter Parker who's like, "Hey, nice costume, guy." But I didn't get it. They gave that to Hal Sparks. But then, two months later, out of nowhere, we got a call saying, "Hey, would Phil be interested in doing something different in the movie?" We're like, "What is it?" "We can't give you the script, we can't tell you, just yes or no?" Even though this was before the MCU, they were still very, very secretive about everything ... and for an old comic book blerd, a chance to be in a Spider-Man movie? Hell yeah! I'll do whatever! I don't know what it is, but I'll do it — yeah! It turned out to be something I had never heard of before or since in my Hollywood career. Sam Raimi, the director, felt like this big action fight scene between Spider-Man and Doc Ock, he wanted it to have heart for the movie. So he said, "I can't just use a bunch, 45 extras. Hire me eight real actors, and we're going to spread them out amongst the extras so if I want to show the emotional feeling of this, I have somebody I can cut to. Or if we want to throw in a line..." So he hired a bunch of us to just be there to act in the background of this action scene. I was like, "Yeah, I'll do that."

Standing up to Doc Ock: 'A wonderfully human moment'

Just a few years removed from the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, the story beat in which a group of everyday New Yorkers stand up to a supervillain in an attempt to protect one of their own resonated with audiences in a big way.

Alfred Molina, actor ("Otto Octavius/Doc Ock"): There's a wonderful moment where someone says, "Look, he's only a kid." And then the shot of Tobey lying down, I think he's upside down and he's slightly coming to, and they take the mask off. And I remember that there was a sense that this was a very important beat in the movie. And when all the passengers on the subway car come forward and go, "You're going to have to come through us," I remember thinking that this was, in a way, the heartbeat of the movie. That for all the technology, all the special effects, all the smashing and all the noise, this really was the heartbeat of the film — that it was about just the humanity of it all.

Ray Lykins, stunt double ("Doc Ock"): I would've done something like that myself, being from New York, too.

Bob Murawski, editor: There was this real strong feeling of New York unity, and the New Yorkers coming together in the face of that adversity. So the scene on the train was definitely an extension of that, and designed to show Peter's sacrifice.

Scott Stokdyk, production visual effects supervisor: That's kind of in Sam's DNA, connecting with the people like that. I've gotten to know him pretty well over the course of a lot of movies, and I think it's from his beginnings in Michigan — it's like he really connected with people.

Peter Allas, "Train Passenger": The day 9/11 happened, I was on the Long Island Railroad train a few stops away and my friend's wife called me and I got off. I experienced all of that, so it was very personal to me. And I thought that was a really nice, added powerful touch to the film. The problem was a lot of people in that sequence were not from New York. And I've always said that only Chicago got a tremor of it when the Hancock building was threatened and that was thwarted. I think the Seattle ferries, there was a couple bombs that were set up and the FBI caught that. I don't think California to this day still has any reality how deep that was. But boy, you go east of Mississippi, you go into New York, Philadelphia, Boston, Pittsburgh, Chicago, Detroit, it resonates so strong still.

John Dykstra, production visual effects designer: That was in a time when the polarization wasn't amplified, right? Polarization was there, but the very vocal extremes didn't have the amplification, the megaphone, whatever you want to call it. So it wasn't the people shouting at each other so much. It was people living their lives with — you live together. You're less judgmental. It's more about a common agreement on a social compact, and that social compact is, generally speaking, whatever our difference is, we know what's right and we know what's wrong, and we pretty much agree on that. I think that was one of those moments, and Sam's really good at including that in the narrative.

Phil LaMarr, "Train Passenger" (uncredited): I ain't never seen a bunch of people barely getting paid anything carrying a dude worth 20 million dollars! I was like, "Oh, damn, I figured they would bring in like six stuntmen in there to carry Tobey."

Peter Allas, "Train Passenger": The coordination of once we lift him and bring him back, that's very important. I think that draws to the drama. The music helps, by the way too, nice additive moment. But I really liked the juxtaposition after he's down. And Sam kept talking about the gentleness. So you have what you talked about, right, this New York, post-9/11 FU. And by the way, I was there for that. I remember watching all New Yorkers defiantly — some to a fault, judging the wrong people by a little bit of prejudice. But I saw New York like a Joe Lewis punch to the head and then get back up, like you're fighting Mike Tyson now and not afraid, almost within a 24 hour period. I think that's what he brought in that sequence. You have the fear, no question, you have to have the fear. It's ridiculous not to have the fear. And then it's like, "Okay, if we go down, we all go down together, but you can't take this away from us."

Alfred Molina, actor ("Otto Octavius/Doc Ock"): Peter Parker is a reluctant hero. He didn't ask for this, in the same way that Doc Ock is a reluctant villain. He didn't ask for it, either. And I always think that simple fact has always made the difference between the Marvel and DC characters. The DC characters very often come out of a sense of moral duty. They do this because they feel it's important. Whereas for me, this is just my view, the Marvel universe is about people who somehow end up like this without even ... "What the hell? I've got to do this now?" And that gives it a humanity, it gives it a kind of, I don't know, something we can all relate to. And I think that scene in the subway car when all the New Yorkers come together and protect him, that's a wonderfully human moment. We did talk about that, and we did talk about how to play that. But in terms of the significance of it, I think that became apparent to us all, I think, after the event.

Peter Allas, "Train Passenger": Everyone came with a great attitude all day, and Sam was very humorous. I remember him giving a note to somebody saying, "Now that was very good if, let's say, we were doing the TV version of something. But we're creating something here." And I love that about him.

Bob Murawski, editor: But then of course, the scene is turned upside down when Doc Ock comes in and basically slaughters everybody. That's typical Sam, of having an emotional moment, but then also making it not so saccharine that the characters aren't made to suffer, to a degree.

Spider-Man 2's legacy: 'This was a super important scene'

20 years after "Spider-Man 2" debuted, the folks who worked on it look back fondly on the end result.

Scott Stokdyk, production visual effects supervisor: I know [Sam] spent a lot of time on it. It's hard for me, of course, to get in his head and see what's important to him, but what he did for us for visual effects, which was amazing, was to make a scene that was kind of a test VFX scene, where we could go in and shoot it early. So, we'd actually have a sort of pre-shoot for a week or two, and it was usually the origin of the villain. So, there's a little Doc Ock scene of him coming to life in the lab. We shot that and I know that was important to Sam to set that up, but the amount of time we spent on that versus the amount of time we spent on this scene is maybe a tenth. So, just by wandering in on editorial, seeing what he's working on, seeing amount of energy he put into the storyboards and pre-vis, I could tell this was a super important scene to him, and I think he was happy with it. I think we all felt really good about it at the end.

As I'm working on a movie, the longer I work on it, the less objective I am about it, and I really can't tell if I'm working on a good movie or not. And I have to treat everything like it's "Avatar" or whatever [laughs] — "This is the most important movie of my life right now" — because I can't guess whether it's good or not. I think where I get satisfaction is if a lot of people see the work, it's rewarding, and if a lot of people have a good positive emotion from it. So, I think I do remember people coming out of screenings and being really excited and happy, and that was great.

But I will tell you one other thing, and it really made an impact on me. I don't remember whether it was on the first or second movie and I was in New York and every time we would shoot a scene with Spider-Man in a costume, crowds would gather. They'd block him off — "don't come into this area." But I just remember this one teenage girl came up and just crying to be so excited to see Spider-Man. And I'm like, "Wow. You know what? Spider-Man means so much to people. What a privilege to be working on something that evokes that kind of reaction." So that changed my perspective for all the rest of the Spider-Man movies. I'm like, "Okay, this is something special. I don't know whether it's going to be a good movie or not, but people are going to care," and that's pretty cool. That's a good feeling.

Bob Murawski, editor: I'm glad people, after all these years, remember ["Spider-Man 2"] and like it. For the longest while people would say, "Oh, what other movies have you worked in?" And I would say, "Oh, you know the Spider-Man movies, not the new ones, but the original ones." They would say, "Oh, you mean Andrew Garfield ones?" And I'd say, "No, actually ones before that." They've rebooted Spider-Man so many times now, which is funny. But I guess it shows how beloved the character is.

And I think it's great that people still respect the ones that Sam did. Because, like anything with Sam, every shot is important. And the amount of detail and thought that goes into every single shot, and every single angle, and every single bit of action, is just something that I really care about, and Sam really cares about. Nothing on those movies would be left to chance.

Scott Stokdyk, production visual effects supervisor: As visual effects have evolved, it's like, how do you use it best? And I think at the time, we were pushed to the very limit of what we could achieve. But the way Sam did it to give an emotional payoff, for me, was really, really satisfying. Because if you just have this big spectacle and it doesn't have an emotional payoff on it, it's forgettable. And I think it's through Sam's design, direction, and the editing of this that it became more iconic. I hope I get to work on more things where it all comes together like that, because you feel really lucky when it does all come together.

Dan Bradley, second unit director: I was a stunt man, and I literally kind of got into directing second unit because I got tired of spending a day doing super exciting sh*t and just seeing amazing stuff while I'm in a car chase or something, and then I go see a movie and, "What the f***? They didn't show any of the experience that I had." It's just boring. It's actually kind of challenging to capture the actual adrenaline that happens when you're doing that kind of stuff. And anyhow, even if you do a good job capturing it, there's a lot of people along the way who can kind of f*** that up. So, we were super excited. I was super excited. I said it 20 years ago: This will never happen again. Because I did three movies back-to-back-to-back that were all great, and to this day, it's like, "Yeah, I worked on 'Spider-Man 2,' the good one."