A Jim Carrey Classic And An Infamous Anime Have More In Common Than You Think

Spoilers follow.

Ah, the double feature. Old Hollywood studios devised it as a way to run (B) movies too short or cheap to merit full price, but there's something undeniably fun about watching two movies back to back. The success of the unofficial double feature that defined 2023, "Barbenheimer," suggests I'm not alone in feeling this; comparing two films is a fun exercise, especially if you can find unexpected similarities.

Two masterpieces are back in the news this week in a great coincidence: "Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind" (directed by Michel Gondry and written by Charlie Kaufman, who were almost deterred by the similar memory-bending "Memento") celebrates its 20th anniversary, while anime classic "The End of Evangelion" received its first-ever official U.S. theatrical release.

"Eternal Sunshine" is a sci-fi love story; Joel (Jim Carrey) discovers his ex-girlfriend Clementine (Kate Winslet) had all her memories of him erased; he decides to do the same to his memories of her. "The End of Evangelion" is the conclusion of the TV show "Neon Genesis Evangelion," spearheaded by Hideaki Anno, then working for Studio Gainax (Anno co-directed "End" with Kazuya Tsurumaki). In "End," teenage mecha pilot Shinji Ikari has the fate of humanity put in his hands — and he blinks.

These films seem too different to even list together; they were made on opposite sides of the world, for one. One is live-action, and one is animated. One is a small-scale romantic drama, one is about a biblical apocalypse. But "Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind" and "The End of Evangelion" are about the same thing: lonely people trying to wall themselves off from others who've hurt them and realizing that's no way to live.

The End of Evangelion

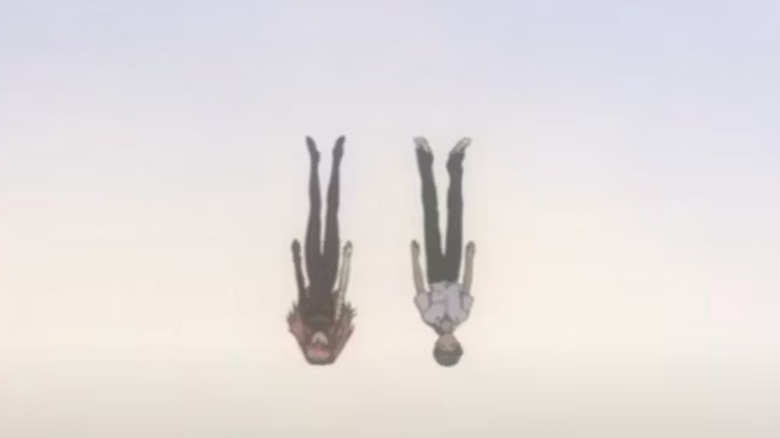

Let's run through what literally happens in "End of Evangelion" — Shinji, granted divine power while in a mental breakdown, chooses "Human Instrumentality," where all the souls become one. "Neon Genesis Evangelion" often referenced the Freudian concept of the "Hedgehog's Dilemma" (the closer people get, the more they risk hurting each other). Instrumentality is the solution to that dilemma; you can't misunderstand someone if you can share their thoughts. Shinji realizes this painless existence is no answer at all and rejects it, returning to life and leaving others the option to do the same.

"The End of Evangelion" is a violent and disturbing movie, and it sometimes feels like Anno is telling his audience to get a life. Still, though, I get annoyed when people emphasize "End of Evangelion" as sicko s**t as if that's all there is to it, or like it's a project of Anno's spite. It's a movie about how someone could be pushed to the point that they'd want the whole world to vanish and that demands empathy. Writing for Mubi, critic Willow Maclay described the film's narrative as, "an apocalypse as metaphor for surviving a suicide attempt."

The lynchpin moment is Shinji's last conversation with Misato Katsuragi, his surrogate mother figure. Shinji, depressed, despairs to Misato: "All I ever do is hurt people. So I'd rather do nothing at all!" So Misato tells him all about how she's continued to make mistakes and hurt others time and time again in a cycle of only slow improvement. Living comes with regret and you can't evade that.

That's the crux of Shinji's decision to leave Instrumentality. He's warned that he'll be hurt again and admits that himself, too, but he's finally ok with that; seeing his friends again is worth it even if there'll be pain down the road.

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind

"Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind" gets surreal in its middle stretch (set inside Joel's subconscious) but it's definitely the more accessible of these two movies. The science-fiction trappings are way more subdued, while the story is more intimate. The premise and emotions are high-concept too; who hasn't wished they could forget something painful? The memory-destroying procedure, like Instrumentality, is an act of self-destruction in the name of avoiding a deeper hurt (memories make us who we are, so deleting them is akin to murdering another version of ourselves).

Like "End of Evangelion," "Eternal Sunshine" argues that we're all in the cycle of making the same mistake. The film's deceptively non-chronological structure (it opens with Joel and Clementine meeting for what appears to be the first time but is actually after their memory losses) reflects this, as does the ending. Despite knowing everything that happened and how their relationship could easily fall apart again, Joel and Clementine decide to give it another shot.

In doing so, they acknowledge it was a mistake to try and forget each other. As Joel goes further back in his memories, his resentments fade and he remembers the reasons why he loved Clementine in the first place. If the good times don't outweigh the bad, they at least make them worth it.

"Evangelion" has a similar idea contained in Shinji's mantra of "I mustn't run away" — avoiding pain or trying to forget it is a hollow existence. There are many times throughout the series when Shinji leaves his responsibilities but ultimately comes back. His choice to leave Instrumentality is the ultimate test of this.

Reckoning with Shinji Ikari

You might be familiar with the "He just like me FRl!" meme, referring to how many of us have pet characters we overidentify with. Why? Because we see our own struggles reflected back by theirs and it's comforting to know we aren't alone. Joel and especially Shinji are two of mine. Admitting it feels like self-flagellation (weak-willed, romantically unsuccessful men? Not anyone's vision of who they want to be), especially since understanding where this empathy comes from means in turn recognizing how their problems are self-created. I can't hate Joel or Shinji but it's not because they're perfect.

Early in "Eternal Sunshine," Joel muses to himself, "Why do I fall in love with every woman I see who shows me the least bit of attention?" Well, because he's thinking only about himself; he's not seeing the humanity in any of those women, just a box he can slot them into. Before they get together (seen late in the movie), Clementine warns him that she's not some manic pixie dreamgirl who will bring spice to his life at no emotional fee. And yet, Joel craves love on his terms the whole time they're together.

Shinji's father Gendo Ikari, a sinister and enigmatic presence in the series, is ultimately revealed as his son's foil in "End of Evangelion." Gendo is too afraid of others and crippled by self-loathing to open himself up, so instead, he wants to reunite with his late wife Yui (Shinji's mother), convinced only she can love him. He even cloned Yui, naming the result Rei Ayanami, as an instrument of rejoining with the genuine article.

A world with no walls around our hearts would be Hell

Rei defies Gendo by declaring "I'm not your doll." Like father, like son: Shinji sees people as dolls too. Since Gendo abandoned him as a child, he's perpetually afraid of rejection. Thus, he wants others to always cater to his emotional needs without repaying them. Opening yourself up to others? That's an easy way to be hurt. When Misato or his crush/bully Asuka act in ways contrary to his view of them? He's repulsed. Shinji's character embodies the solipsism of depression in ways that are painfully real and shows why self-pity — whether literally like Shinji feels for himself or projecting your own onto his character — is nonconducive to healing. If you stay a Shinji long enough, you'll become a Gendo; both characters realize that, but only Shinji gets the chance to be better.

The movie's last scene (Shinji strangles Asuka, she caresses his cheek, he stops and cries, and she calls him disgusting) shows that pain, miscommunication, and conditional acceptance have returned to the world. Joel and Clementine share almost the same unfiltered connection Shinji and Asuka did in Instrumenality; they received the tapes the other made listing everything they hated about each other while they were together. They're feeling the quills of the Hedgehog's Dilemma, but choose to get closer still. The roller coaster of contradictory empathy and revulsion that Shinji and Asuka experience in two minutes is one Joel and Clementine will embark on together for however long their next go at love lasts.

"Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind" and "End of Evangelion" both find room for hope in fatalism. You don't choose to live or love someone because it's assured things will work out ok in the end, but because the alternative is, well, returning to nothing.