Reaching Daybreak: An Oral History Of Battlestar Galactica's Final Season [Exclusive]

This article contains spoilers for "Battlestar Galactica."

15 years ago, on March 20, 2009, "Battlestar Galactica" concluded its run with the series finale "Daybreak," and man, what a frakkin' good show that was. A reboot of a short-lived 1970s series, "Battlestar Galactica" follows a starship fleet searching for the fabled planet Earth after humanity's home, the 12 Colonies of Man, are destroyed by their robotic creations, the Cylon. I was a little too young to watch "Galactica" weekly on its first airing, but thanks to the magic of Netflix, I downed the whole thing the summer before I entered high school.

It was the first show of that length (four seasons, 70+ episodes) that I watched from beginning to end. I love "Star Trek," but I'll always appreciate "Battlestar" for going further than even the Final Frontier dared push. "Battlestar" co-creator Ronald D. Moore got his start in TV writing on "Star Trek" and set out to make something even more radical than "Deep Space Nine," the darkest "Trek" of them all.

Still, to paraphrase the finale of the "Star Trek" show where Moore first wrote, all good things must come to an end. And the Galactica's last flight — it's a divisive one. Some reviews, both contemporary and retrospective, contend too many poorly laid twists left the show feeling like less than the sum of its parts. In particular, there was the twist in "Daybreak" that the show was actually happening in prehistory. I won't argue it's a seamless finale, but it's a confident one and I can't throw out everything good about the show, too.

In honor of the show's anniversary, I spoke with several writers and actors to get a peek at what the journey of the bifurcated final season looked like from the inside. Even if some of their memories have faded in spots, their passion for the show hasn't.

The new genesis of Galactica

One of the people I spoke to was co-creator David Eick, who shared the story of the show's genesis, way back at the very beginning.

David Eick: I had just completed a pilot with Sean Cassidy for USA Network that had died and so I was really depressed, walking on my treadmill — which I occasionally still do. And the phone rang, it was David Kissinger, who's Henry Kissinger's son, but at the time was the president of Universal TV. He said, "One day you'll look back on this conversation as the one that got you your house in the south of France," and I was like, "Okay. Yeah, I'm bummed out with it." And Universal TV had been in mid-prep on a "Battlestar Galactica" two-hour new series. Not a reboot per se, I think it was more of a sequel. Bryan Singer was helming and nobody liked the script that much but it was a put deal with Fox and they were looking for any way out.

What Kissinger was saying was we were foolish to have sold this to Fox in the first place, we have our own sci-fi channel in the corporate structure [Sci-Fi, now known as Syfy], we should have just sold to them. I'm like, "I've never seen 'Battlestar Galactica,' all I remember about it was the cheesy rip-off of 'Star Wars.'" [...] I was just like, "I need to start over again," and [Kissinger] said, "Fine, fine, fine."

So I set about looking for a writer and Ron [Moore] was somebody who had consulted on a show I had overseen as an executive when I was running development for USA Network and Sci-Fi Channel. I [got] to know him through that relationship and now I've crossed over and I'm back to producing. So I called him in and, honestly, he wasn't my first choice just because I had other guys I was closer friends with and I knew Ron from "Star Trek" and all I knew was I didn't want to do anything like "Star Trek." Whatever "Star Trek" was, I didn't even know that much about "Star Trek," I just knew that it felt antiseptic and simplistic. I know people love it and I take my hat off to it, I'm sure it's none of those things, that was just my impression at the time — we're talking 2001 here.

But what happened was Ron came into my office, and it was February of '02 at this point, so we're four months or so after 9/11. And we start talking about the ironic parallels between this goofy, cheesy '70s "Battlestar Galactica" that begins with this holocaust, this destruction of a planet, and how oddly it mirrored what we were reading in The New York Times and watching on CNN and whatever. And that's where he and I started to really bond because I didn't know how to not do "Star Trek," but here was a guy who, oddly, knew everything about "Star Trek" [...] and what I didn't know about Ron was that he was sick of "Star Trek."

He had lived with it, he had been on it, he had deviated a bit but had, at that point, really not worked very much outside of it and so I think he was excited by the challenge of doing the kind of space show that I think would cut against all of the tropes and cliches. We came together so effortlessly on those principles that the details from then on, all the early discussions, were fun, productive, and, by the time we pitched it, we just had it down.

When you were making the pilot miniseries, did you know that this was going to lead into a series, or was it just assumed this would be a one-off?

Eick: Well, no, we did not. One advantage we had is that because again, I had been behind enemy lines and I knew a little bit about what was going on at the company having been an executive there, I advised Ron — and he had not an iota of resistance — to write it, shoot it, cut it like it's a pilot. Don't have any illusions about it. [...] The way we ended that was Sharon coming out and saying "We'll find them" and you're going, "Holy sh*t, she's a Cylon" [...] I think that it was such a cool chilling ending that they went with it. We just treated it like a pilot from jump street.

One little-discussed advantage of that set of circumstances that I always marveled that we got away with, is because it wasn't a pilot, it was technically a miniseries, the deals that we made, we had series holds on Eddie [James Olmos, Commander Adama] and Mary [McDonnell, President Roslin] and maybe Katee [Sackhoff, Starbuck] and maybe James [Callis, Baltar] and Jamie [Bamber, Lee Adama] [...] I think Six had a series hold, Tricia [Helfer] [...] but not on anybody else. So, so many of the characters that became the lifeblood of the show, Gaeta and Tyrol and Tigh [and] Dee and I can go on and on, we never had to jump through network approval hoops, we would just cast them, they were just basically day players with no series holds on them.

Not that they hadn't worked before, certainly, Michael Hogan [Tigh] had done a ton of work, but they weren't stars, they weren't names and most of them were Canadian so they weren't being viewed as, "Oh, we got to lock them down so they don't get away." They were all available to sign series deals a year and change later when we finally got the green light. And it's remarkable to me because I know we go through such pain casting these things and every little role has to go through nine hoops of approvals. You just look at how significant those supporting actors became to the success of the show creatively that you scratch your head at why the process has to be so complicated.

Shipping out on Galactica

Over the course of its run, "Battlestar Galactica" built a formidable writers' room.

Mark Verheiden: I had left "Smallville" to do some other stuff that didn't quite fly and I got a call one day from my agent, [who] said, "Have you any interest in this new 'Battlestar Galactica' show?" The first season was already out, but I didn't even know it, because I just hadn't been paying attention. And I remember saying to my agent, "What, that old '78 show?" But they sent me the first season and I watched it, binged it over a weekend, and just went, "Man, I got to be part of this." Long story short, I went in for an interview and I was hired. So I came in around season 2, episode 5 or 6, as I recall.

Michael Angeli: I was already on a show called "Medium." And I really wanted to be on "Battlestar Galactica," but I had to fulfill my contract, which was one season with "Medium." So in the meantime, I did an episode of season 1 [episode 7, "Six Degrees of Separation"], which just sort of fell into place. But then after that, I got out of my contract and I joined the show full-time for seasons 3 and 4 and "4 and a half" or whatever.

Jane Espenson, whose credits include "Firefly," "Angel," and many more, also previously wrote for "Star Trek: Deep Space Nine." I asked if her "Trek" work was how Ron Moore found out about her, or if it was the work she had done in the interim that got her the job on "Battlestar Galactica."

Jane Espenson: Neither! It was something earlier than that. I used to pitch stories at "The Next Generation." So I would come down from Berkeley where I was a grad student and I would pitch stories to them there. And I was usually pitching either to Brandon Braga or to Ron Moore because they were the kids on staff. And years later after that, I did get to write a "Deep Space Nine" [episode], but Ron wasn't there. And then years later when I wanted to go on "Battlestar," I told my agent, "See if Ron Moore remembers me from pitching to him all that time ago when I was still in grad school." And he did, and he was aware of my subsequent work, or maybe he looked it up. So, yeah, he claimed he remembered me. I like to think it's true.

So season 4, I actually joined a little late. I had been put on staff at "Eureka" under an overall deal at Universal. I don't think I was there for more than a couple of weeks before we realized there was a way to sort of shuffle the cards and I got put on the "Battlestar" staff. So I came into a thing very much in progress, and I remember going to [writers] David Weddle and Bradley Thompson's office and seeing plans for the final season up on their whiteboard and just sit there, big-eyed, reading, "Oh, that's going to happen? Oh, my God, oh, my God." It said Cylon reveal. There was so much wonderful stuff up on that board, I couldn't believe it because we didn't even know who the fifth Cylon was, I believe, and it said it up on that board.

So I was just entranced. And then, yeah, I got briefed on everything in the room. They all filled me in on what it was. Because I joined in progress. I took over an episode that Anne Cofell Saunders had started and she was over at "Eureka" taking over an episode that I'd started, which is extraordinarily unusual. TV doesn't work like that. But I was thrown right in the middle of, "Okay, go finish rewriting this episode." So I was right away working, right away on my feet and running.

A peek inside the Battlestar Galactica writers' room

During the final season of "Battlestar Galactica," the writers were Moore, Angeli, Espenson, Verheiden, Thompson, Weddle, and Michael Taylor, with one-episode contributions from Seamus Kevin Fahey and Ryan Mottesheard.

Espenson: To help people picture it, this was what I call a couch room. There were rooms where you sit all around a big table and there are rooms where you all sit around on couches. This was a couch room, a semicircle of soft, comfy armchairs and couches facing the corkboard. And Bradley would stand up at the corkboard with the sharpie and the big cards, the big note cards, that size, and write [episode ideas and beats] on them.

Espenson, who came to the staff of "Battlestar" as one of the faithful, compared the experience to her previous work on "Buffy the Vampire Slayer" during our chat.

Espenson: I was a huge "Buffy" fan and just worked like crazy to get employed on "Buffy" and managed to do it. But that was joining in season 3. This was joining in season 4, which since it was the final season, it feels much later. And yeah, my friend, I believe Drew Greenberg, who was one of the writers on "Buffy," told me, "I think you'd really like 'Battlestar' where there's a mix of comedy and drama and really high quality, fun stuff to write. It doesn't have a lot of comedy, but it has everything else you love." And I watched it and I actually disagreed. I think it has tons of comedy. It's just dry and localized. There are episodes that are just hysterical, and Baltar is consistently just so funny.

[Writing for your favorite show is] what you dream TV writing is going to be like when you're a kid watching a show and you're like, "I want to step into that show." "Yeah, but that show is fictional. How could you do it?" "Oh, well, you could step into the place where they come up with what's going to happen and you can walk on the sets." And that, for "Battlestar," maybe more even than "Buffy," it really felt like you were stepping into the show because when you walked onto those sets, you were on the spaceship. There were places you could stand on that set where you could turn 360 and not see anything of a sound stage, just see a spaceship.

Thanks to her unique perspective as the new kid in the room, Espenson was impressed with how the "Battlestar" writers' room felt like a collection of people who'd lived lives.

Espenson: Everybody in that room was an expert in something. Like David Weddle is the world's foremost expert on Buster Keaton, and Bradley Thompson is like a sharpshooter who teaches people how to shoot. And Michael Angeli had ghost-written celebrity autobiographies. Everybody in there had journalism backgrounds and just all kinds of expertise. It wasn't a room full of people who had written for nothing but the Harvard Lampoon. These were all people who had lived lives and accumulated stuff outside of the room. Mark Verheiden's work in comic books. They're all geniuses in their own right, and I felt very out of my league and very privileged to be there and really happy when anything that I wrote made it to the screen.

Sometimes they'll be people who've spent their whole lives writing TV and they're really, really good at writing TV and that's fantastic. But every now and then you'll find someone who is also a paramedic, or was a doctor. I worked with a radiologist on a sitcom. And I think those people are incredibly valuable. Anybody who wants to get into TV writing, I think a really good thing to do is accumulate something, even if it's just, do a correspondence course to get a private detective's license. Like come into the room with some other thing you can do. It just makes you so much more valuable and gives you a richer life.

As for Ron Moore, while I regrettably wasn't able to speak with him, everyone I did talk to had glowing praise for how he ran the show.

Eick: Ron ran the writer's room so I can't speak for him, but he and I both shared a tendency to want fearless involvement, no politics, and a lot of hiring dogs and letting them bark.

Angeli: Ron Moore, stories about him and being great in the room are legion. He was the best guy. He gave us a lot of freedom and he trusted us, the writers [to] let us surprise him in some ways, so it was great.

Espenson: Ron is awesome, very supportive. Just had a delightful time every time I talked to him. He would host the writing staff at his house and he would pay for a big retreat every year where we would go off to Tahoe or somewhere, and break story with the whole staff. Put us all up in a fabulous lodge. He was fantastic. And he often wasn't there. He was spending a lot of his time elsewhere in Northern California with his family or working on other projects. So Mark Verheiden was really running the writers' room. So we would break the story with Mark in charge and then get Ron on a speakerphone, and Mark would pitch the story out to him off cards that Bradley Thompson had put up on our corkboard. And Mark would pitch it to him, and we could hear Ron was maybe going through security at an airport or something, and yet was able to just listen to this story and say, "Okay, that sounds good, but your end of act three really should be the end of act two, so you've got too many..." Or, "act two and act four are too similar." So he would have these precise notes even at a distance. So it was still very much his guiding hand coupled with Mark Verheiden's room leadership that was running that show.

'The most collaborative show I ever worked on'

Verheiden: The great thing about Ron, aside from having an amazing vision for the show, was that he was open to flexibility in telling the stories. You could come up with an idea that might not be what was in the outline. It came up as you were writing, which sometimes happens. Ideas come up when you're writing the script, it didn't hit you when you're doing an outline. And if it was something that interested him, he'd go for it. In past and future shows, I've learned how uncommon actually that is. It's not common to have someone embrace things that go off what was originally approved.

Espenson: I suggested that we make Felix Gaeta gay and that was revealed in [extra webisodes]. And I had been really reluctant to pitch it. On a lot of shows in that era, when you suggested that, the showrunner would go, "It's not for us," or, "Have we earned it? We've seen nothing to indicate this. We haven't earned it." But if you suggest the things that would make you earn it, they go like, "Oh, that's kind of weird. Where are we going with it?" It was very hard to do that at that time. But when I suggested it to Ron, Ron said, "Oh, we should have done it earlier." And I was like, "That means I should have pitched it earlier." So that's the thing I learned, is that Ron was so democratic, so open to suggestion, anyone on the set even could suggest a change to a scene and Ron would take it and run with the change.

We could make huge changes in our scripts. It was encouraged to veer off the outline, add something. You could kill a character if it's the right thing to do. The other writers coming after you will have to adjust what they're doing. It's the most democratic and bottom-up show I've ever worked on, where it was open to all suggestions and things continued to change. And if I'd picked up on that earlier, we could have had a gay character in the main run of the show, not just in the webisodes. And that was, I won't say it was on me, but I wish I had realized earlier that this was a show in which I could suggest that.

Tricia Helfer: This was my first series, so I didn't have anything to base it on. But having been in the business for many years since I now realize how collaborative this process was and how open the writers and producers and creators and Ron were with hearing us out. And yes, actors are almost always the last to find out anything on a set, which, as a responsible adult, I find very annoying because it gives us the least amount of time to process and to work on things and to not only learn lines, but just to work on it as a professional.

I understand a lot of times I've been told, "Well, we don't want to give it to the actors too soon because sometimes there's revisions and then a scene they liked was taken out, or then the actors are talking to you about their schedules and all that kind of stuff." I understand from both sides, but I do think that the actors are treated like children too much and generally are given the material way later than I think they should be given it.

There was some of that on "Battlestar." We certainly didn't have it as fast as some other departments, but it was one of the shows that we did have time to prepare. We weren't given it the night before type thing. We were usually a script or two in advance, an episode or two in advance, sometimes two episodes. And they were very gracious with, if there was a big story arc coming up, they would pull you aside and talk to you about it in advance. So you could either prepare it a little bit or get your head wrapped around it.

When you shoot a movie, you know the beginning, middle, and end when you're going into it. When you're shooting episodic, you don't know aside from the script or maybe if you have the script ahead. And sometimes, especially in more serialized type shows, I would hate to go to do a scene and make choices in one way and then find out three episodes later that my character knew all along or did something else or whatever that would have affected how I played that scene.

And I think with "Battlestar," they were very gracious with us and tried to let us know in advance. The buck always stopped at the top and you could come up with an idea that you thought was great and it would get shot down, or we'd go, "Okay, let's try it and let's try it the other way." But overall, it was probably the most collaborative show I've ever worked on

Katee Sackhoff: I had an incredibly collaborative relationship with David and Bradley. I worked with them on one of my first series that I was the lead of called "The Fearing Mind" in 1998, and they wrote one of my [most fun] episodes from that series. It was a show on Fox Family that lasted only nine episodes, but I remembered them from that. That previous relationship with them gave me the courage to talk to them, and so Bradley and David very clearly wrote a lot of Starbuck's best episodes. Not to say that the other writers didn't, but I didn't speak to them as openly and as honestly as I did with David and Bradley. [Note: The pair wrote "Act of Contrition," "Scar," "Maelstrom," and "Someone to Watch Over Me," so I think you can see where Ms. Sackhoff is coming from.]

Espenson: Getting to put words in the mouths of characters you loved, knowing this is what Baltar would say and writing it and then hearing James Callis say it, which sometimes he didn't. Sometimes he ad-libbed, and irritatingly what he ad-libbed was always better than what was written, which you feel like, "Well, what am I here for then?" He is fantastic. They were all so good. Getting to hear any of them say your words.

Deciding season 4 would be the end

None of the "Galactica" alums I spoke to recalled the surprise at the series wrapping up with season 4; the show had come with a promised endpoint — that the leads would find Earth — and season 3 ended with a shot of our blue-and-green planet on the other side of the galaxy from the Galactica, the most blaring hint of its existence yet.

Helfer: We knew pretty early on [it would be ending], I think because Ron Moore had said from the very beginning that he saw it as a five-year run. And to us, that's what we did. It came across as four seasons, but it took us five years to film between the miniseries and then the seasons. It was the way they aired it. They did season 2.0 and 2.5 and season 4.0 and 4.5. But for us, we were up there for five years filming, and so to us, I always say five years.

It wasn't really a surprise, and I guess you always hold out, I don't know if it's "hope" or also you never really know until you have the final, "Yes, it's the end," because sometimes they're like, "Oh, we're going to give you another couple episodes with this or that." But none of us were shocked that it was ending. I knew it was doing well for Sci-Fi, so I don't think any of us would've been shocked if they had decided to do more seasons. But knowing what Ron had said from the get-go, none of us were really surprised.

Verheiden: The, I think, guiding principle in going forward into [season 4] was — there were several, but actually I looked back and was reviewing what season 4 was about, and it's really about the conflict in various ways, as this war has gone on for so long. So there was a conflict between the Cylons, who were trying to decide if they should embrace the trip to Earth and humanity versus not doing that, just wiping out the humans once and for all.

There was certainly a force growing inside the fleet, very unhappy to discover that there were Cylons among them and that in fact working with the Cylons may be the only way they could survive. That became a big part of the second half of season 4. And then there was the conflict between religion, between the gods and the one God. And Baltar played a pretty big role in pulling that forward. So we were exploring all these conflicts while later in the season, Battlestar Galactica itself was crumbling, it was falling apart, and they could no longer sustain themselves in space. It just had been too long in space. So something had to give.

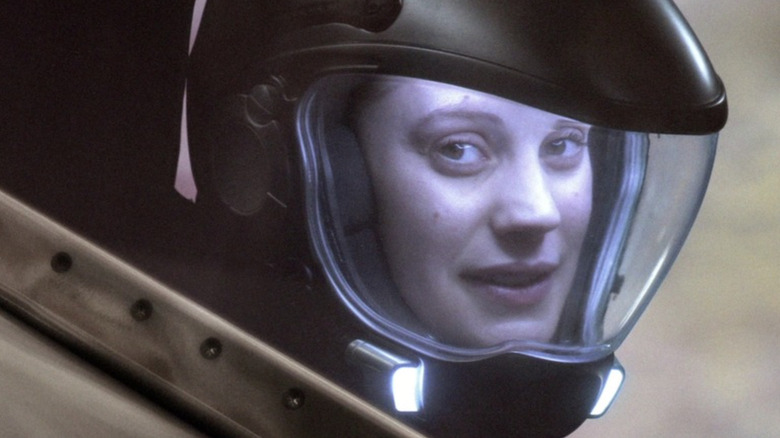

Season 3 ended on a doozy, revealing Tigh, Tyrol (Aaron Douglas), Anders (Michael Trucco), and Tory (Rekha Sharma) as four of the long-teased Final Five Cylons (something the writers had not planned ahead of time). Then, Starbuck (who'd died a few episodes earlier) returned, promising to take the fleet to Earth. Was she a Cylon? She wasn't, and, according to Katee Sackhoff, was never going to be. But the mystery endured.

Sackhoff: So in the very beginning of the [third] season, we were told that "We don't know who the Final Five are, but we know without a shadow of a doubt they are not Adama and Starbuck." So we knew that we were not Cylons. So when that death happened and subsequently her coming back, I never questioned if she was a Cylon or not.

With season 4 having to run with the baton passed by season 3, the writers' room went to plotting. The "Battlestar" room used the process of "breaking" story observed in many other TV writers' rooms (case in point: "Breaking Bad") where the writers collectively map out episode beats designed around four/five act structures (remember commercial breaks?) before getting individual episode assignments.

Angeli: First, before the season started, we would have a vacation, a gathering at some place. And before we started season 4, we went to Reno, Nevada. We rented two big houses and we broke the stories during the day, and then at night everybody went gambling.

Espenson: I generally feel like I earn my money when the script is broken and I'm out writing dialogue. I'm not generally someone who is shaping the episode in the room. I stepped into a really functional room where all those guys knew the show so well. They'd all been there at least one season previously. I'm not sure when they all started, but they all knew it so well.

You'll notice Eick has no episode credits in either half of season 4. Well, he had to step back due to other commitments. His heart remained on "Galactica," but he trusted the team even in his absence.

Eick: By the time season 4 came around, a couple of things happened. I had sold the [sarcastic] whopping hit "Bionic Woman" reboot to NBC and my overall deal shifted. And obviously, "Bionic Woman" was this enormous financial risk that required a great deal of attention. So, the upshot was Ron was still full-time so it was easy for the studio to be, I don't want to say pressuring me but encouraging me to focus on a lot of this new stuff. Therefore, I am more objective about season 4 than I can possibly be about any of the first three seasons.

I was still in communication with Ron Moore and, occasionally, the studio would call me and go, "Could you just make sure this makes sense?" But I would say my involvement was cut in half or more vis-a-vis the first three seasons. The most involvement I had in season 4 was the meeting Ron and I always had before the first writers' room meeting which was to discuss the big picture. What's the season going to be, what are some points on the grid and, naturally, I was involved with and well aware of how it ended. But it was that moment and then it was sitting in the cutting room and being involved on the finale. So very involved at the beginning [of season 4], very involved at the very end, almost not in the center of it.

The saga of a Starbuck

Kara Thrace is without a doubt one of the most popular "Battlestar Galactica" characters (we at /Film certainly think so) and, no disrespect intended to Dirk Benedict, is so much more than the Han Solo-lite Starbuck of the original series. Her death and resurrection feel like a meta acknowledgment that the show couldn't go on without her; there is no Galactica without Starbuck. On the DVD commentary for season 4, episode 1, "He That Believeth In Me," Moore even says they shot down the possibility of bringing back Starbuck as only another "head" character because the show and fans needed her back in full. The show itself dodged hard answers on how Starbuck returned, but Sackhoff walked me through her interpretation.

Sackhoff: Before we were sent the script I was requested to get on a call with Ron Moore and David Eick, and on the call that's when they said, "You're going to get a script, everyone is going to get a script, and you just need to know that you are coming back, but don't tell anyone." I was like, "Okay, sounds good." So I kept it a secret as long as I could, but the unforeseen problem arose from that, keeping it a secret, was that the character of Starbuck was so pivotal to the show that crew members and cast started to think the show was being canceled. [...] I think they told Eddie that I was coming back, and Eddie thought that it was cruel to do that to the crew because so many of the crew had started thinking the show was potentially getting canceled. So he announced it. So basically as soon as Eddie found out, I think everyone found out.

I also never questioned what [Starbuck] was, I never asked. Part of it was that I was still, I'm not going to say I was relatively new to the industry because I've been acting since I was 14, but I was relatively new to finding my voice as a woman and as a young woman in the industry. I was always taught to be seen, not heard, and so I didn't think that it was my right or that I had any power to ask questions like that. So I didn't, I didn't ask. So I still don't know what she was. I still don't know. I think that she was probably an angel, I do believe that she died on that planet. I know that she did — that, to me, was very clear. What else was clear to me was that she had to die in order for people to find a new home. In my belief, what that meant was that Kara knew she had to leave for an angel of sorts to take her place to lead people to Earth.

So you consider pre-death Starbuck and post-death Starbuck different characters?

Sackhoff: Absolutely, 110%. So I always [viewed] the character that came back as not being Starbuck, and that's why she was so desperate and so manic for a lot of the beginning, because this entity, this angel, had to convince people that she was Starbuck in order for them to trust her.

This might be a complicated question, especially since you see the two Starbucks as different entities, but in her heart of hearts, would you say her true love is Lee or Anders?

Sackhoff: Starbuck always loved Lee as a best friend, and she was probably in love with him. She was in love with both of them. I think Anders aligned with who Starbuck was, or became, and aligned with who she was. Starbuck needed Lee, she needed him, he was her rock. Then when she finally started becoming her own, Anders was there and Anders was that person. But I also think that she was tremendously afraid of a relationship with Lee, for whatever reason. I think that he brought out the strongest aspects of her, but also the weakest aspects of her, and she felt weak around him. She felt like she needed him too much, and that was too much for her.

The real bombshell of our interview, though, is that despite how close Starbuck is to her heart, Sackhoff has never watched the full show — at least not how the fans experienced it.

Sackhoff: I watch everything one time, and then I never watch it again. The problem with "Battlestar" was we were given the DVDs if we wanted to watch them, with no special effects at all to them — rough, rough, rough, rough cuts. So I watched them that way to make sure that my performance was sound, that was the only reason I watched it. So I've never seen the completed show, no. [...] I watch my work to critique my work, not enjoy my work. Then it just got too daunting. It's 78 hours of television. But I must say, my husband has also never seen it, so there is a world where I think that we need to do a re-watch of some sort.

Watching without special effects, your memories of it must be very different from most people's.

Sackhoff: They're very different, and so I don't remember certain things, because like I said, my entire purpose in watching something was to critique the performance and that was it.

Playing the Cylons, behind and on camera

In the reimagined "Battlestar," the Cylons aren't only chrome-plated "toasters," they're artificially-grown humans akin to the replicants from "Blade Runner."

Eick: Really, the big breakthrough was [making] the Cylons humanoid because we were looking at basic cable budgets and you're certainly not going to put men in suits, so you're talking CG. And at that point, CG wasn't advanced enough to really be reliable anyway, not to mention the costs. So, it's like, "Well, how do we have Cylons as a character?" and that thing became such a big solution to everybody that it was one of the key, if not the key decision. Because then you could do what a show about robots [...] can't do which is reflect the paranoia of the times. Everyone's talking about sleeper cells, and if your next-door neighbor is Arabic in any way, suddenly you're nervous and you're not sure. These were all very touchy, very sensitive issues at the time, so it played into the drama wonderfully. And as we all know in sci-fi, you could be much more overt and deliberate in your discussions of the issues of the day because you're always [exploring them] through this prism of something fantastical.

We're told in the mini-series that there are 12 human Cylon models, which meant the Cylon actors, like Helfer, had the challenge of playing different shades of the same character, some less sympathetic, some more. The most infamous scene in the pilot miniseries sets the dichotomy early. Before the nuclear inferno, "Caprica Six" holds a human baby in awe — and then snaps its neck, walking away with a grimace you wouldn't expect from a killer robot.

Helfer: I had talked with [director] Michael Rymer about this. It was written that it was just like "snap the baby's neck and walk on." And I [wanted] to bring in some empathy. And it wasn't like an empathy of, "Oh, I'm going to save the baby." It was still, we're going to annihilate this planet, this colony. [Caprica Six] wasn't second-guessing herself. It was more just I wanted to bring in a fascination of in my mind, it was like she had never really seen a baby before, or at least up close. She had certainly never held one. And seeing the innocence of this tiny little being just starting out life where her empathy went to was, "I don't want this to suffer. So I'm still going to do my job, and it's still going to die, but I want it to die a quick death, not with the bombs going off in a few hours and maybe being separated or struggling or whatever."

I hate to even think about it. But to me, it was a mercy killing and it was brought off of just, I personally am not a big baby person. I don't have kids. I never had that instinct to want children. I much prefer animals. You give me a baby and I'm like, "Uh, what am I supposed to do with it?" But it's very hard not to look at a baby and not just be sort of in awe of it. And that to me is more what it was with Six, and then a mercy killing and seeing that look on her face when I walked away, that it wasn't something she enjoyed doing. That I wanted to bring in — that this was not just some malicious killer. That brings in the whole aspect of the series of who's in the right and who's in the wrong. You could see many things from the Cylons' perspective after a few seasons. It's that gray area, and obviously killing a baby is not a good thing. But in the context, that was her reality at that time, that's what I wanted to get across.

Helfer's assignment grew in scope as the series went on, especially since she proved up to whatever acting challenges they threw at her.

Helfer: From the beginning, I had Caprica Six that sort of morphed into Number Six [aka Head Six], and I didn't really know the difference at the time. And then in the first season, I had Shelly Godfrey in that one episode ["Six Degrees of Separation"]. And I remember having discussions at the time, "Caprica Six was a little more sultry, whatever. If [Shelly] comes in accusing Baltar, who's going to believe her if she's slinking around?" And they had written in the glasses, obviously for a story point that they're left over. Adama finds them. But I was like, "Can I make her mannerisms a little bit more librarian-esque?" And they went with it.

And then I didn't get another taste of it until halfway through the second season with the Pegasus episodes and Gina. By that time, I was really craving it because I was tired of playing [Head Six]. I felt she didn't have a storyline of her own. And I felt it was a lot of the schtick. The schtick of nobody else seeing her was getting old. How many interesting new ways can we bring her into the room or have her appear? And so the Pegasus episodes came at a very good time for me because I was starting to lose a little patience with [Head Six].

My idea on it was identical twins that were raised separately. Some of them were almost like cookie cutters of each other, but [some] had drastically different [personalities]. Caprica Six, her job had been to fall in love to get into the defense mainframe to start a relationship with Baltar. And within that, she ended up falling in love with him that we find out. But then there was some other ones that had no interaction with humans, and were definitely just with the Cylon mantra of humans are bad and we're going to annihilate them all and bad. I also tried to gauge how much human interaction each one had and what that human interaction was to be able to determine how I would play that character keeping within the frame that we already had for that character.

Humans and Cylons working together became pivotal to the series' endgame.

Verheiden: I think especially once you discover that the Final Four, Final Five had been living among them, Tigh especially, but also Tyrol, you realize that they had been working together. And if they were working deep cover, it was a very deep cover because they didn't even know it. So I guess they were sleeper agents, or could be considered that. So [the humans and Cylons allying] just evolved I think, out of that.

Then the idea that, to survive, you had to find a way to find some sort of peace. You couldn't keep an ongoing war like this forever. There were finite amounts of resources on Galactica and the fleet anyway, all of which had been chipped away over the four seasons. There were no longer any pleasure ships, where people went to have drinks or anything like that — that was all gone. There was no longer any good food that had been turned into some sort of algae derivative. Things were getting pretty ragged. So [...] desperate times call for desperate measures. And they just required Adama to ultimately do the thing he couldn't stand to do more than anything, which was to align himself with the Cylons.

The different faces of Number Six

The initial leader of these rebels Cylons was another Six: Natalie Faust. In the "Last Supper" cast photo for Season 4.0, Helfer appears twice, first in the photo's center as Caprica/Head Six with her trademark red dress and blonde hair, and then off to the left as Natalie.

Helfer: I wanted to play [Natalie]. At that point, there was some division within the Cylons [...] of some wanting to just annihilate [humanity], some wanting to work with [them]. And I think to me, [Natalie] was showing growth and hope and learning of "maybe this is not the best way, and maybe we had it wrong and maybe we can ..." I do feel like she had the best of intentions of really wanting to figure out how to work together. And her life was cut too short with [Athena]. But to me, that death hurt because I knew it was out of range [of the Cylon resurrection ships], and she was really gone, and I just felt like she was really trying to do good. So I wanted to play her a little bit more direct, a little bit more honest and straightforward. She wasn't trying to play games, she was trying to let people know her intentions. And I liked Natalie. She was one of my favorites.

One of the more left-field decisions (in a season full of them) was romantically pairing Caprica Six with Tigh, who was going through self-loathing after realizing he's a Cylon himself. Helfer admits she found the pairing "a little odd," but relished it for the chance to finally share scenes with Michael Hogan.

Helfer: Michael Hogan is just such a wonderful actor and a wonderful human being that for me, it was just exciting to work with him more one-on-one. And then there was the whole pregnancy. I found it heartbreaking that [Caprica Six] wanted that so bad, and she knew she was second in his heart. It was sad, that was a sad relationship for me. But me personally, to work with Hogan more one-on-one is just a treat. He's such an aware actor. I've told this anecdote a few times but when we were doing the miscarriage scene or when she uses the baby, we did the whole wide angle and everything like that. And then they're like, "Okay, we're moving on to the close-ups of Kate, Vernon and Michael Hogan, Ellen and Tigh." And I'm laying there on the medical bed and whatever, and Michael looks at me and he sees that I'm in the place. I'm emotional. I'm whatever. He looks at me. He goes, "Just hold on a minute."

And he went over to the team, the director and the DP, and was like, "Do Tricia first, do her close-up first." And so they altered the light. They changed what they were setting up, and they did my coverage first, and then afterwards went to their coverage. And that just shows how selfless he was as an actor and how tuned in and present he was. He could tell that I was ready to shoot my coverage. It still kind of goes, "Oh, I don't really see those two characters together." But on a personal level, I really enjoyed working with him.

One of the recurring Cylons is Leoben Conoy (aka Model Number Two, played by Callum Keith Rennie). Leoben is the most earnestly religious of them and has a stalker-like obsession with Kara. Still, Leoben ultimately joins the rebel Cylons and makes peace with Kara. He's last seen discovering the body of the "original" Starbuck with Kara and running away in fear when she asks him for answers. That ending always felt like a bit of a loose thread to me, and Sackhoff was able to enlighten me as to why there was no more Leoben in season 4.5. — logistics.

Sackhoff: Here's the problem with a show like "Battlestar" and an actor like Callum. Callum was by far, and still is, one of the best actors I've ever had the opportunity to work with. He inspired me and taught me so much just by existing in scenes with me. Callum is a movie star in Canada, they couldn't afford to keep him under contract, nor do I think that he would have wanted that. I don't know, that's speaking out of turn I guess. But you can't write a story for a guest star or a recurring character if you don't know if you're going to be able to get them.

So Callum was unavailable and too hard to get, because of his schedule and potentially the cost. I have no idea what he was making, but you add a bunch of those things together and it makes a character untenable. I know that just because people ask me why I didn't go back for the last couple seasons of "The Flash." It makes it impossible when you've got to pay a recurring character tons of money and shoot them out in three days, and not use them after midnight on a show that's largely shot at night. It makes things difficult. But that is the reason why Callum wasn't there — I don't believe that he was available, and that sucked.

The mid-season writers' strike

"Battlestar Galactica" Season 4.0 ends with episode 10, "Revelations." In the closing minutes, the fleet finally reaches Earth — and finds not a second chance, but a nuked wasteland. The episode ends with a devastating tracking shot, capturing each of the main characters' reactions one by one as the camera makes a circular pan, showing the full depth of the apocalypse.

Eick: I remember my own shock when I was reading scripts on a plane or wherever I was at the misdirect. We found Earth. "Wait a minute, Ron, we're only in episode 10. What the f*** are you talking about?"

That was the end — for six months, at least. "Revelations" aired in June 2008 and the show returned for Season 4.5 in January 2009. Before the last 10 episodes had been shot, though, there was the 2007-2008 Writers Guild of America strike. That left the cast and crew in the same limbo the fans were — during those months (the strike began in November 2007 and ended in February 2008), there was a chance that "Battlestar" could be canceled and "Revelations" would be the end.

Angeli: We all stayed together [during the strike] and picketed the same place and hung together and kept kind of working without working. And some of us had projects that weren't affected by the strike that we were working on, like writing our own pilots and stuff like that, that the contracts had already been signed before that strike. But that strike, that was murder. That was a lot worse than this past one [in 2023], and this past one was pretty bad. But I mean, the one good thing about it is it got us to spend more time together.

Espenson: That was a long strike, too. I mean, the latest one was longer, but 100 days in the middle of the season. Our seasons were already kind of bifurcated. You'd do half a season and go away and come back if I recall, and then have this 100-day stretch. And I remember Ron was very involved in the picketing, and I remember walking the picket line with him at Paramount.

Normally we were over at Universal where we shot, but one day we were at Paramount and we walked together for a little bit, and he was saying, "When we get back together and we can start talking about the show again, I've had some thoughts about different things we can do." I no longer remember what things got changed during the strike, but I know that having that time where none of us were working on it, you can't help but your wheels continue to turn. So I take that as proof that the story ended differently to some extent than it would have without the strike.

Helfer: I remember we were all pretty ... "freaked out" is maybe too strong of a description, but I remember when we knew and we were getting the call, "We're waiting for the strike to be called," and we're finishing up halfway through the season and all of us just going. At the place that we were in filming, it could have been an end — a very depressing end, mind you. But it could have been an end. So it was more so that we just didn't actually know if the strike went on long enough if Sci-Fi would just call it and say, "Okay, the show's done," instead of ramping back up and shooting another 10 episodes. It was a very disconcerting feeling knowing that this could end the way this was written, very depressingly.

Much different than when we knew it was the ending, and we all had our moments of bursting into tears because it was our last scene, or somebody else's last scene. And the props auction house that had got all the props, they would literally pull things out of the actors' hands as you were wrapping. But we were all very emotional because we knew it was the end, but emotional in a good way. The end of the show, and we're all ... it was different when that strike was. That was like, this could potentially be the end without us knowing it. And how disappointing would that be?

Why would Sci-Fi kill their golden goose, especially as it was so near the finish line? Helfer, while admitting she wasn't privy to any of the decision-making discussions, says there was palpable uncertainty.

Verheiden: I can only speak for myself, [I was] very nervous. We of course were worried when we went on strike because we had just finished episode [10]. It's the one where they land on Earth and it's a mess. It's a nuclear wasteland. And we did think at the time that if the strike went on and the powers that be made that decision, they could probably end the show there, which of course we did not want at all. And thank goodness they didn't.

Helfer: The show was doing well at that point. It had won a Peabody. It had been nominated, I think, director and writing for an Emmy or technical Emmy or whatever it was. So we knew the show was like the Sci-Fi darling at that point. But it was also a fairly expensive show to make in those days. And you just never know in this business. I don't think we all really thought that it would get the cut, but who knows? If the story was to go on for however long, it is a business at the end of the day and they may say, "Well, it's going to cost us more to keep the stages and keep this and whatever, and let's just let it go."

Sackhoff: I honestly didn't think about it. I have no idea why. For whatever reason in my brain, I just always thought we were coming back.

Eick: Ron was very involved in the union — he may still be, we don't get a chance to catch up as often as we used to — and I was learning through him about how negotiations work, why the issues that the Guild was fighting for were so vital, why the resolution to it was really a good thing. I mean, he was walking me through all that stuff. And it's funny, it speaks to our relationship [...] It goes back to those first days when we found ourselves talking about Al-Qaeda instead of "Battlestar."

We have a lot in common in terms of our politics and our interests in issues of the world. And so, yeah, we were making season 4 of "Battlestar" but I think, most of the time we talked, we were talking about why unions are so f***ing awesome and why you need them and what's going on here. [...] We had more fun sometimes talking about that stuff.

Mutiny on the Battlestar Galactica

During season 4.5, the anti-Cylon faction of humanity ultimately tries to take control of the fleet by force.

Verheiden: We had talked about doing mutinies in earlier seasons, and it was pointed out, I think probably by Ron but also by Brad and David [Weddle], who were very versed in the military part of this, that mutinies are very rare. So it would take a lot to get to a point of mutiny on our ship. We wanted it to take a lot. We just didn't want to feel like it's something that happens because it's dramatically just, "This will be a cool episode." It had to be something we built up to. And they were right.

The mutiny unfolded over two episodes around the midpoint of the final stretch: "The Oath" (scripted by Verheiden) and "Blood on the Scales" (by Angeli). Despite how dark things have gotten on Galactica, these are the two most exciting episodes of season 4.5. Mark Verheiden agrees.

Verheiden: When we came back after the strike, we screened the episodes up through the episode where Dualla committed suicide [Season 4, episode 11, "Sometimes a Great Notion"]. We watched them back to back, like three and a half hours' worth, and I remember thinking at the time, "This is one of the darkest shows, it has gotten very dark." Which I love. I embrace dark, I've worked on horror. I love dark shows, but I said that, "The show has just gotten dark." And so with "The Oath," the fun part was to bring back ass-kicking Starbuck and to have her back in protecting Lee, and doing the right thing, and that was fun.

The other part was to have Adama and Tigh, who have finally patched up their issues — well, some of them — after Adama found out Tigh was a Cylon, have them work together in the midst of this mutiny to — basically they have to survive in that episode and then they have to triumph.

But the scene that I really love, and I was there on set for the show, for me was watching Adama turn on the two soldiers that were holding him and Tigh captive, were going to walk them to a cell or to their death or something. And he just turns on them and says, "All right," just turns that Admiral on and that stops them in their tracks. That was just a great moment. We tried to figure out how they get out of this, and I finally just thought, well, Adama would just turn and go, "I'm done with this." So that's what we ended up doing.

One of the mutineer ringleaders was an obvious enough pick: Tom Zarek (played by the late Richard Hatch, the original series' Apollo). A political subversive introduced as a resident of a prison ship, Zarek had always been power-hungry and a frenemy to Adama and Roslin at best. His partner, though, was Felix Gaeta (Alessandro Juliani), an earnest member of Galactica's bridge crew.

Angeli: For a long time, we dithered over where we wanted [Gaeta] to go and really we needed sort of a bad guy from within instead of some bad guy coming from without and an outsider or whatever, or some Cylon or something like that. At the time, we needed our bad guy from within. We figured that Gaeta was the most loyal and knew the most and had been passed over so many times that he would be the guy. So we sort of mapped out his character arc and where he would go.

Verheiden: I believe that I originally had wanted to start "The Oath" with a flashback to the miniseries that showed a very fresh-faced Gaeta who's absolutely loyal to Adama. And contrast that with where we've ended up now, which is Adama basically working with Cylons, more or less, and Gaeta absolutely repulsed by that idea. [...] What I always liked about the evolution of his character in season 4 especially, was that I always thought Gaeta in a lot of ways was right on his side, the way he was thinking. It was insane for the humans to want to form an alliance with the Cylons. So in some ways, I had sympathy for his side and Zarek's side.

And on the other hand, when you see it from the Admiral, you realize that the fleet had to make some adjustments or they were going to just die in space. So that part was the character part to me that was interesting, was watching Gaeta's evolution from being this loyal soldier to a guy who just said, "I can't put up with this anymore. I can't take it."

Gaeta's descent is sealed in season 4, episode 6, "Faith," where he's shot in the leg by Anders, and the limb is ultimately amputated. The following episode, "Guess What's Coming to Dinner?" (scripted by Angeli) sees him resting in the med bay singing aloud to dull his phantom pain.

Angeli: One of the things that Ron said to me was, "You know what? I want a song for the episode that you're doing," where this is where we figured out that we wanted Gaeta to lose his leg. [...] So I came up with the lyrics and my wife came up with the melody, and that's what Gaeta sang when he got the phantom feelings in his leg, he would sing that song. It was so amazing to see [Alessandro Juliani] do the song because [he] had a really tremendous voice to begin with. He sang opera and had sung on Broadway and whatnot, so he was just tremendous. He sang while he was lying on his back, pretty much, which is really hard to do.

After that, Angeli carried Gaeta's story to its final chapter: his execution, alongside Zarek. During our conversation, Angeli cited the 1980 Australian film "Breaker Morant" as an influence on the episode's ending. Based on real events during the Second Boer War (at the turn of the 19th/20th century when the British Empire was subjugating South Africa), the film follows three Australian soldiers tried for war crimes. They're found guilty and two of the three — Harry Morant (Edward Woodward) and Peter Handcock (Bryan Brown) — are executed by firing squad, much like Gaeta and Zarek.

Angeli: That's kind of where we came up with the whole idea of an execution with two friends, or two comrades, that are waiting to die.

"Breaker Morant" ends with Woodward singing "Soldiers of the Queen" over the execution's aftermath. Morant's spirit as a poet and convicted traitor found itself again in Felix Gaeta. As for Hatch, Angeli tells me he was reluctant to leave the show early even when it was wrapping up, but they convinced him: "Well, this is it for you, but we'll make it grand."

Angels on Galactica

Circling back to Helfer's discussion of playing the semi-invisible Head Six, this character went from an assumed hallucination of Baltar's to a literal angel. This tracks with religion in general becoming a bigger and bigger part of "Battlestar Galactica" as it went on, particularly in season 4 where the mystical becomes literal. Per my conversation with David Eick, that whole development was serendipity.

Eick: [Religion] was part of the underlying texture, but it wasn't nearly as overt as it became after we pitched it, after Ron wrote the first draft [...] Number Six had a line in the four-hour miniseries pilot where she says something about God. I think the line was "God is love" or something to that effect, and it was just this weird allusion to this underlying mythology we had discussed but very, very subtle — you weren't supposed to necessarily understand what she meant, not at that point.

We were terrified that we were going to get killed, because you can't have the bad guys referred to God in this way that is antithetical to how bad guys are supposed to be presented and, certainly, how God is supposed to be referred to on an American TV show. The head of the company at the time, the guy in charge of the studio and all the networks, was named Michael Jackson. No relation. [He] was a Brit, he was an expat from the BBC who didn't have any of these American puritanical hangups. And he read that line, he was like, "What the f*** does that mean? More of that. What is that all about?" and we were so shocked that we got the opposite reaction. If he had been an American, we probably never would've. But because he was the boss, everyone got in line and they wanted more of that. So we pushed it and made it much more of a prominent part of the Cylon narrative. And again, to play up that irony of good guys worship gods and bad guys worship one god.

So much of the religiosity, the aspect of the show that takes on the metaphysical, that evolved almost episode by episode, certainly season to season. And I would say very little of what you see in season 4 was conceived of or imagined, let alone discussed as early as those first days.

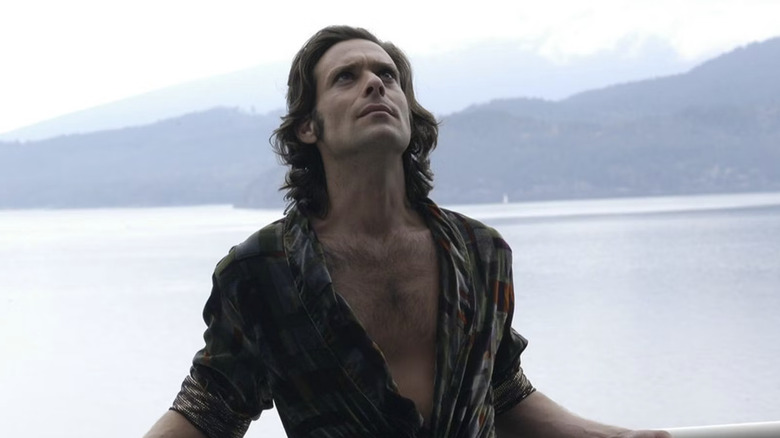

Dr. Baltar - bad guy?

In a show defined by characters who juggle the good and bad in their hearts, Dr. Gaius Baltar (James Callis) is the most conflicted of all. Seduced by Caprica Six, he helped the Cylons destroy the 12 Colonies. He's a cowardly weasel too, but not a sadist. Over the course of the show, his character journey is the bumpiest. In the season 2 finale, "Lay Down Your Burdens," Baltar is elected President of the fleet ... and soon after turns into a collaborator with the Cylons. He's tried and cleared in the season 3 finale, "Crossroads," then spends season 4 spreading the Cylons' monotheism among humanity; that religious turn becomes crucial to the series' theological endgame.

Verheiden: [Baltar is] an interesting character just because of his torment. I mean, he always seemed to have less than positive attributes and yet sometimes he could pull out surprisingly positive ones. That was fun to work with, that duality, although he was always driven by selfish motives, I always thought. However, when he came into the one God situation and became adherent to that, that was interesting just because it was a new dimension to him. I don't think we'd seen his spiritual side and we had always embraced the characters finding that there's a spiritual side to this as well as the hard science and the science fiction side. So to lead Baltar to that place where ultimately he's exactly a savior, but a peacemaker within the fleet, which is insane, was ... a lot of good turns for that character. I think James Callis had fun playing him.

Espenson, though, tells me she would ultimately deem Baltar a "bad guy" who never quite changed enough for it to matter. She cites her penned episode "The Hub" (season 4, episode 9), where Baltar admits his original sin to President Roslin.

Espenson: "The Hub" that I wrote, we learn that he knew. [...] I remember in that episode the revelation that makes Laura rip his bandages off and leave him to bleed to death was that he was more culpable than we had previously known for sure. And I always felt like that moment made it very clear he was a bad guy. Now, bad guys can learn and grow. I think Baltar learned and grew. I don't know if it's going to stick. He is someone who is very motivated by himself. He is a self-centered character. I think that's clear and that never leads to any good.

Finding the wrong Earth

In "Daybreak," the characters find a fertile planet (thanks to some God-given navigational intuition by Starbuck) and name it Earth so they can say they made it to Earth after all. The ending cemented "Battlestar Galactica" as a show about faith first and foremost; sci-fi hallmarks like spaceships and robots don't have to mean the future. The alums I spoke to were able to share their memories of both saying goodbye to the show and processing its conclusions.

Espenson: I was actually stumped by "All Along The Watchtower." I was like, "Well, it has to be the future because of the song." And Bradley Thompson looked at me and he said, "You're assuming that song only happened once? And that recording of that song only happened once?" I was like, "Oh, right, if this has happened before and it'll happen again, we may be dealing in a circular thing in which events will line up enough so that song is recorded over and over again in millennia. Okay, well now you sold me. Okay, now it can be the past." So I was more open to the past after he said that. I was fine with that. I'm not sure, left to my own devices, what I would've chosen. I might have gone with the future just because "Star Wars" is in the past.

Sackhoff: I think that when Starbuck died [in "Maelstrom"], she said goodbye to Lee, she very clearly said goodbye to Lee when she said, "Let me go." Then this angel felt like, that last scene with Anders was very special for me, because that person, that angel, was going to be with Sam. So a lot of people are like, "Well, she should have ended up with Lee." She didn't end up with either one of them. Starbuck died. So I think that those episodes were really important to me, especially that last episode with Michael Trucco, that last goodbye to him. That felt really special.

Trucco and I were really, we all were really good friends, but that scene was really special to me. The scene, saying goodbye to Adama, that was really hard because it was ... I believed in that moment that angel, whatever she was, was saying goodbye for those people, not Starbuck. That she was making sure that they were going to be okay, that was saying goodbye to Lee and asking him if he was going to be okay. That's why you see the little smile on her face when she realizes he's going to be okay, and then she leaves. That was the last thing that she was sent to do.

Helfer: The very last scene I shot, if I'm remembering correctly, was a big shoot-'em-up running through the corridors with an AK. I think that was the last shot of the entire production because I remember the champagne being busted out after that. And it was a late at night or early middle of the night type thing. But I do remember that was the champagne being brought out and we're wrapped. It wasn't some big emotional scene. It wasn't like Six and Baltar are looking over the ridge [and] him saying, "I could be a farmer." It wasn't that. No, it was guns and explosions and that type of thing.

Eick: But my biggest regret was because I think I was on "Bionic," I was unable to be on the set for the final day of principal [shooting] which was Baltar and Six firing weapons during the battle in the CIC. And Ron called me, he was very emotional. [...] And now I look back and it's like, "I missed that for f***ing 'Bionic Woman,' are you kidding me? They would've survived without me, I could have left for that afternoon."

Verheiden: Mixed [reception] is good because a lot of people loved it, some people had problems with it. I found that Ron was trying to strike a balance between the spirituality and the science-fiction and the Cylons and the various plot threads that we had going. I actually wasn't there that much for breaking [the finale] because I was up in Vancouver in production. So it's hard for me to talk about how they came to that. To my mind, it's a very good ending for the series. Now I say that and then I go, of course if they had picked it up for another season, we would've figured something out. I don't think that was in the cards for Ron or David either, but I'm just saying from my point of view, I thought we would've figured something out to keep going.

Eick: I [still] love it, obviously, it's my show and I love, love, love the emotional potency, the power of "Daybreak Part 3," just how it all comes together, [but] I would not have brought back Ellen Tigh. I think you bring back Starbuck and the audience will give you that, but I don't think I would've continued to bring back dead characters. [It] became a hat on a hat. I think I probably would've talked Ron out of Head Six and Head Baltar having awareness of the other-selves [...] Head Baltar [communicating] with the real Baltar, that also falls in the category of a hat on a hat to me. So, if I had to criticize a couple of aspects...

The one that I think gets the most criticism [about the finale] that I certainly would've argued harder about if I felt strongly against it and — ultimately, I trusted Ron's big idea — that Kara was probably a zombie angel of some kind [and] her metaphysical nature was never finally explained. [...] That is such a give but, in a lot of ways, it's the only elegant solution that doesn't require a lot of sci-fi exposition or explanations or that kind of thing. I thought there was an elegance to it, and certainly a high-wire act to pull off. It's obviously a mixed opinion whether it was successful. I'm at a camp that says that aspect was successful, I only wish it had been left as a more unique experiment without some of the other, as I say, more high-concept ideas.

Helfer, the first main cast member to appear onscreen back in the mini-series, got to sign off the show with her usual scene partner James Callis. ("We worked together so much that we just almost had a shorthand after not too long, really," Helfer recalls.) The pair played the angels who looked like Six and Baltar, observing present-day New York City and wondering if, as humans rediscover AI, the cycle of creation and destruction will repeat once more.

Helfer: Those [exterior] scenes are always hard because you have so many extras. And then of course, Ron Moore was doing a cameo, which was fun, but [the Head Six scenes are] my least favorite scenes to do, just because I didn't even necessarily know exactly what I was talking about in the scenes. It wasn't as fun to shoot. It was fun because Ron was there and it was a fairly simple walk and talk. But at that point, we all had mixed feelings about the finale. I liked it. I liked that it wasn't all wrapped up in a bow and everything. It was a new beginning.

Did the crew pay any mind to the reviews?

Eick: Well, the show got a lot of love from the critics as it gained traction, but when it first premiered, they weren't that kind [to] miniseries. So I was just accustomed to this half-and-a-half business. With the really crazy episodes that were going to, I know, rub some people the wrong way. I don't remember it surprising me. Again, I knew the Kara vanishing thing was going to be controversial, it's not like we thought everyone's going to go, "Yeah." It was deliberately controversial, I think, in some respects. But I would say, and again, I'm not taking credit for that idea or any of the writing of the episode, certainly, but I think Ron and I do share also a certain impish irreverence, a tendency to want [to] needle.

So I think why I was able to get on board with that decision [about Starbuck disappearing] was I understood it as something subversive, something that would not be what they all wanted and not be what they all expected. As long as it was pulled off elegantly, and I think it was. And by the way, so much credit goes to [director] Michael Rymer. That idea could have been shot in a way that it just did not work at all. It was a high-wire act but I thought it was subversive and needly. I knew it was going to be controversial and I liked that it was controversial. I take no credit for it, but I did like it.

The Battlestar Galactica legacy

"Daybreak" was the chronological end of the four-season journey, but it wasn't the last chapter of "Battlestar Galactica" produced. In October 2009, a direct-to-DVD movie called "The Plan" was released, retelling the first two seasons from the Cylons' perspective and shedding light on what the "plan" they had (as described in the title sequence) was. "The Plan" was written by Espenson as a matter of fate. Since she came onto the show late, she became the only writer still under contract and assumed the responsibility in place of David Weddle and Bradley Thompson.

Espenson: There had been work done on ["The Plan"] before. So that basic structure, thank God, had already been worked out, but there was still a lot of fact-checking of, "Did this character know this at this time? Can we believe that they might have known it? And did this scene happen before that scene?" Oh, it was a logistical nightmare. And even when you'd think you'd have it worked out, you'd get a call like, "Wait, somebody who worked on the show at that time says this actually doesn't make sense for that," or, "We don't have this anymore." Oh, it was a nightmare.

We had to do things in certain orders because sets were being demolished, and it was some rough sledding, an uncomfortable outdoors Vancouver stuff. But I love a lot of what we came up with and the way it played out there was no plan. These Cylons were just as fallible and as driven by pettiness as humans. And this inexorable enemy was just people with parental issues, who felt abandoned by humanity and were petty princes striking out. I loved that whole thing. I thought that was quite deep, and it was really fun writing for different versions [of Cyclons] that we had only had a few minutes with, or whole new ones.

Edward James Olmos also returned to the director's chair for "The Plan." He'd previously directed Espenson's first episode of season 4, "Escape Velocity," and she shared what it was like making an episode with him.

Espenson: I got to work a lot with Eddie Olmos, which was amazing. And watching him in casting, watching him, even after we knew we were or were not casting this young actor, he would still spend minutes with each one and usually get them to cry, not by being mean to them, but by making them act. Coaching them through how to evoke a memory or whatever to make them cry, and they would all cry. And you were like, "Oh, man, he is a coach." And he was a caring coach with every actor. In TV, the writers are the bosses of the directors. So technically you could say, "Hey, Eddie, I'd like another take there," or, "I'm not sure we got the right version of this," or, "This line actually means that. Can you make sure that meaning comes through?" But I don't recall doing that. I mean, Eddie knows what he's doing and he is the Admiral.

Two prequels followed: "Caprica," following the creation of the Cylons 58 years before "Battlestar" on the eponymous colony of man, and "Blood and Chrome," following a young William Adama fighting in the Cylon War. But "Caprica" was canceled after one season and "Blood and Chrome" didn't make it past the pilot. Eick, who worked on both, gave me his insights on why these didn't take off.

Eick: That 30,000-foot "what is the show, what is not the show" thing that we had on "Battlestar," we did not have on "Caprica." Ron's involvement vacillated so there was less consistency and less reliability and, as we shored up his absence, I don't think the people we had in place to do that were the right people, to be totally frank. And I think there were maybe some questionable casting decisions with that one, whereas, with "Battlestar," I just feel like we got stupid lucky with so many of those people.

["Caprica"] was always an effortless idea: It was "Dallas" but with artificial intelligence and high tech instead of oil, and it would be a prequel to "Battlestar" and it would illustrate how the war started and those aspects of the idea I loved. I think there were people trying to emulate when Ron would get really hippie-dippy metaphysical with "Battlestar," and then sometimes it'd get a little wobbly. [...] When you don't have his high-wire act ability which is, let's say, successful more often than it isn't and you're trying to emulate it, it can become mush really quick, just like, "What are you talking about here?" So we ran into that buzzsaw.

By the time we pulled ourselves out of it, which we did, by sheer force of f***ing mandate, we figured out "what is this show?" I remember writing out and I think Ron rewrote a proposal to the network for "Caprica" season 2 and it was f***ing tight, man, it was really good. It was 51/49, man, it just went the other way and we didn't get that second season. If we'd had the second season, we may have been able to rescue that one. See, now you got me all worked up about "Caprica."

"Blood and Chrome," same thing. Just down to the wire, let's pick this up, we can make a different style of "Battlestar" that's more of a "Band of Brothers" style of action show and maybe a little more escapist. [...] And the book, the bible for the "Blood and Chrome" show was great. Really good, good sh*t [...] and they just wouldn't buy it, I think, because management changes were happening, "Maybe we need to move on from 'Battlestar," and do what became their decades-long "it's not sci-fi but it's on Sci-Fi Channel" stuff, and it's a shame. I'm not bitter about it, it's just one of those things where [it was close.] "Bionic Woman" was not close.

Despite occasional rumblings of another reboot or follow-up, "Battlestar Galactica" has stayed mostly dormant since the early 2010s. Is this failure to be a "Star Trek"-like media franchise and the controversial final scene proof that the show didn't stick the landing? I don't think so; a show's commercial reach, or its becoming a content farm, isn't the final word on its success. While not everyone was satisfied by the end, it's a cliche for a reason that the journey is what matters, not the destination. As final proof of how "Battlestar Galactica" touched the lives it reached, I'll close with the ending of my conversation with Katee Sackhoff and how playing Starbuck shaped her career.

I feel like Starbuck, her characterization and the way you played her, has defined your career since in a lot of ways. Characters you've played later, like Bo-Katan in "Star Wars" or Dahl in "Riddick," are similar badass sci-fi action women. So, I'm just curious, how do you feel about that?

Sackhoff: I grew up watching science-fiction and action films with my father. My dad was my movie buddy, he still is my movie buddy in the sense that we both have the same adoration of film. So as soon as I was given the benefit of choice in my career, which as a young actor you don't have that benefit, you take whatever jobs you can get because every job begets another job, so I took everything. The moment I had the opportunity to fight for something and then turn something down at the same time in order to do something else, I had two projects sitting in front of me and one was "Battlestar Galactica" and the other one was "NCIS," and I fought for "Battlestar" with every fiber of my being.

Because I knew that character was going to change my life, because if I could just hold a gun one time, I knew that people would start seeing me differently. Because up to that point, all I played was angsty teenage girls that were misunderstood or annoying or just stereotypical blonde characters. I needed to reinvent myself to create longevity in this industry, and I knew that. So I saw this character come up that there was no age attached to her, there was really no feminine descriptor attached to her whatsoever. They just explained who the character of Starbuck was and that was pretty much it.

I knew that this was a career-changing role, and so I purposefully went that direction because it's the kind of film I love to watch. I wanted to be Bruce Willis and Sigourney Weaver and Linda Hamilton. I wanted to be these people because I didn't identify as someone who was strong when I was a kid. I loved to get dirty and I loved to fight with my brother, and I loved to be physical, but there was something about action heroes that had a confidence that I did not have. I loved to pretend like I did. So there was something about them that I adored, and I think that I learned how to play them differently.

I think that because of my own insecurities as an actor, as a woman, as a person, I brought those insecurities into these very stereotypically strong characters, action-based characters. I think what that did was it made them memorable in a weird way, because they were so multidimensional. The strongest female characters that we ever saw on camera were vulnerable, and that's why Starbuck spoke to so many people. I wouldn't change it for the world. I wouldn't change it. I've played so many characters that are complicated and strong and vulnerable and misunderstood, and I just think it's real.