The 'Rigid' Rules Every Twilight Zone Episode Was Supposed To Follow

For a show as ambitious as "The Twilight Zone," with seemingly so many storytelling opportunities to choose from, it's vital to maintain a bit of structure. Not only did the first three seasons stick to a clear 22-minute format with narration and act breaks happening right on cue, but there were clear guidelines on how speculative they should get and how much they should always be asking of their audience. According to the producer Buck Houghton in his 1991 book "What a Producer Does," he and creator Rod Serling established a list of rules that every episode needed to follow. An episode could be about nearly any speculative premise, they decided early on, as long as it remembered to do a few things:

"Find an interesting character, or a group, at a moment in crisis in life, and get there quickly; then lay on some magic. That magic must be devilishly appropriate and capable of providing a whiplash kickback at the tag. The character(s) must be ordinary and average and modern, and the problem facing him (her, them) must be commonplace. 'The Twilight Zone' always struck people as identifiable as to whom it was about, and the story hang-ups as resonant as their own fears, dreams, wishes."

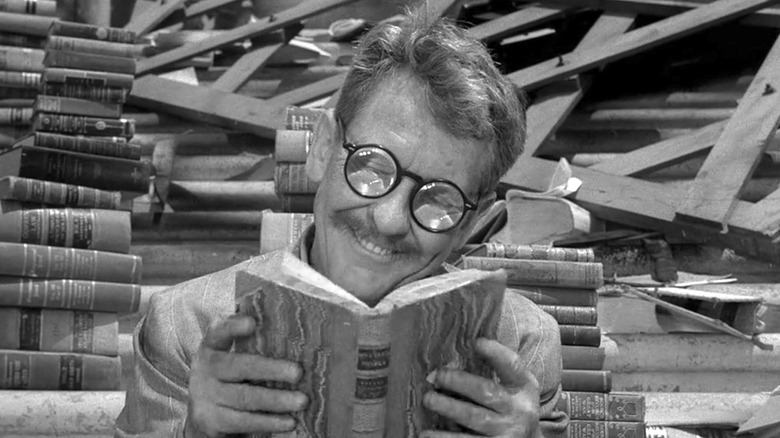

Any fan of the series probably already knows what he's talking about. From Henry Bemis in "Time Enough At Last" to the patient Janet Tyler in "Eye of the Beholder," nearly every "Twilight Zone" protagonist is intended to be relatable. Even if you're not a bookworm like Bemis, you can still relate to the feeling of life forcing you to put off the things you truly want to do; even if you're not living in a world full of pig-faced people, you can probably still relate to wanting to fit in.

Stick to just one thing!

Most episodes stayed true to that first set of rules, not only establishing a sympathetic character but throwing them into the ring as quickly as possible. Nan Adams in "The Hitchhiker" is being stalked by the mysterious titular hitchhiker within the very first scene, just as Robert in "Nightmare at 20,000 Feet" starts seeing the gremlin on the wing almost immediately after Serling finishes his narration. But not only did Serling and Houghton believe an episode should get into its premise straight away — it also needed to stick to just one premise at a time:

"Allow only one miracle or special talent or imaginative circumstance per episode. More than one and the audience grows impatient with your calls on their credibility."

There are some episodes that seemingly break this rule, but the second premise is usually just a natural extension of the first. For instance, the decision in "Eye of the Beholder" to introduce a colony of regular-looking people for Janet to join might seem like a slight departure from the main premise — it's certainly not the main part people remember when they think back to the episode — but it also fits pretty well with the themes established in the first half. The mid-point twist reveals that this hospital is in a strange world with strictly held beauty standards, and the rest of the story explores that world further.

'Must be impossible'

The last of their rules read:

"The story must be impossible in the real world. A request at some point to suspend disbelief is a trademark of the series. Mere scare tactics will not fit the bill. A clever bit of advanced scientific hardware is not enough to support a story. 'The Twilight Zone' was not a sci-fi show."

Here's where the list gets a little dicey because there are a handful of "Twilight Zone" episodes that genuinely don't seem to follow these rules, and many of them are still genuinely good. Season 3's "The Shelter," for instance, follows a group of suburban neighbors fighting over who gets to stay in a bomb shelter during an impending nuclear attack. The twist is that the nuclear strike never comes, and the characters have stooped to such lows against each other for nothing.

Considering the episode's 1961 air date — just a year before the Cuban Missile Crisis and during probably one of the most contentious periods of the entire Cold War — nothing about this episode probably felt impossible or sci-fi to contemporary audiences. As "rigid" as Houghton claimed the rules were, it's clear that there were a few exceptions over the show's 156-episode run, and some of them turned out to be among the very best episodes of "The Twilight Zone."

An impressive feat

Still, straying from your show's main rules only a handful of times over five seasons shows some good discipline. After all, "Black Mirror" (the so-called modern-day "Twilight Zone") would start straying from its main premise after just 25 episodes. "Black Mirror" was supposed to be a technology-focused anthology series, a show that kept on a strict sci-fi (or at least sci-fi-adjacent) focus, but by season 6 it was already throwing in werewolves and smooth-talking demons. A lot of fans actually enjoyed this "Red Mirror" approach, but there is something a little depressing about just how quickly the show seems to have run out of tech-related stories. Serling's series stayed mostly on topic for 150+ episodes, but Charlie Brooker's show couldn't make it to 25?

Then again, "The Twilight Zone" also arguably strayed a bit on one of its earlier rules — "get there quickly" — with its one-hour episodes in season 4. With all this extra run-time to explore its characters, the show was suddenly in less of a rush to jump straight into whatever its speculative premise was, leading to what's widely considered the weakest string of episodes in the series' whole run. The experiment wasn't a total bust, however: season 4's "The Miniature," starring a young Robert Duvall, is one of the highlights of the show, a clear case of the extended runtime paying off.

So, although both "Black Mirror" and "The Twilight Zone" broke their own rigid rules over the years, it's hard to get too upset with them. What's the point of having rules anyway if you don't break them every now and then? Both shows maintained their true focus on exploring the darker, ambiguous parts of human nature; as long as they kept that up, the writers were still doing their jobs.