The Risky '60s Show That Got Axed Halfway Into Its First Episode Premiere

George Schlatter's and Digby Wolfe's 1969 TV series "Turn-On" is one of the most notorious flops in TV history. On the night of its debut episode, an ABC affiliate in Cleveland, Ohio only allowed ten minutes of the 30-minute show to elapse before pulling it from the air, filling the remaining time with intermission-ready organ music. According to newspaper reports from the time, "Turn-On" received many, many angry phone calls. By the time "Turn-On" was to debut on the West Coast time zones, it had already been canceled. It's the only show in history to be canceled in the middle of its debut broadcast.

"Turn-On" was lambasted for being ribald and controversial — there were numerous gags about sex and sexuality — but more than anything, it was just off-putting and strange. The premise was high-concept: in the show's very first scene, a pair of engineers sit down at a computer console and announce that "Turn-On" is the world's first fully computerized TV show. Its comedy sketches are going to be written and created entirely by artificial intelligence. All the skits are presented against a plain white background, a weird sort of nether-space, where audiences see what might be the subconscious of A.I. creating its mechanized version of human comedy. Images pop in and out of existence, a "joke" is presented, there is no logical punchline, and the images vanish. Tim Conway was the celebrity host.

For decades, few were able to see the whole pilot of "Turn-On," turning it into a footnote in trivia books. A few months ago, an enterprising YouTube channel called Clown Jewels salvaged both the complete pilot of "Turn-On" as well as the never-seen second and third episodes, complete with a new intro by Schlatter. This oddball experiment can now be "enjoyed."

A.I. Comedy

The idea of "Turn-On," one might immediately note, proved to be prescient in 2024. Just last year, the WGA went on strike when producers threatened to replace them with advanced A.I. writing tools that would produce scripts automatically. "Turn-On" was, way back in 1969, already pointing out that computerized television would produce nothing but odd nonsense. In a way, "Turn-On" was meant to be anti-comedy, a surrealist exercise exploring what a computerized brain might interpret as comedy. As such, if a sketch is weird, dirty, or nonfunctional, audiences would have to interpret that as the computer brain misunderstanding humanity.

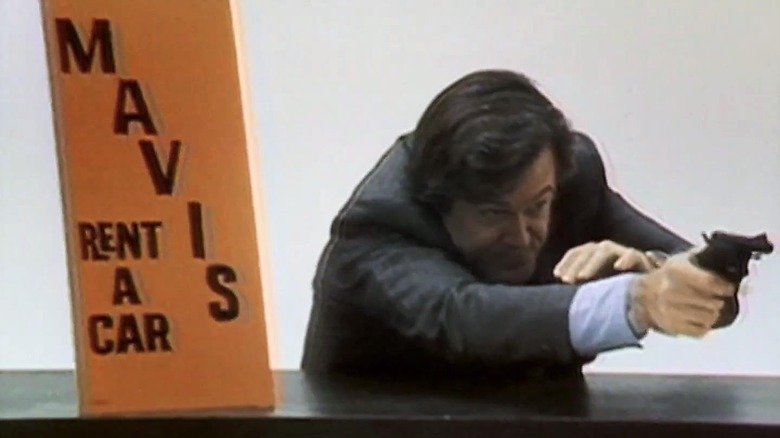

For example: Superman (Conway) flies through the air. A terrorist with a gun pops into existence next to him. "Take me to Cuba," the terrorist demands. Superman looks baffled for a moment. They vanish. This was a reference to a terrorist hijacking an airplane, demanding transport to Cuba, only with Superman standing in for the plane. Was the sketch a mere riff on the "It's a bird, it's a plane" intro to Superman? A parody of hijacking drama? What was the computer brain getting at?

Other sketches were merely naughty. In one of them, a buxom woman in a low-cut dress is blindfolded, about to face a firing squad. The general approaches her and explains that it may be unusual, but for this execution, the firing squad had a last request. This sketch is merely an old-fashioned, sexist joke exploiting a pretty woman. Something like that wouldn't have felt out-of-place in "Laugh-In," a contemporary of "Turn-On."

There was no laugh track and every sketch was accompanied by a hypnotic, computerized "thunking" noise, emphasizing that the sketches were all artificial. It was closer to "Tim & Eric" than "Laugh-In."

What is 'good taste' anyway?

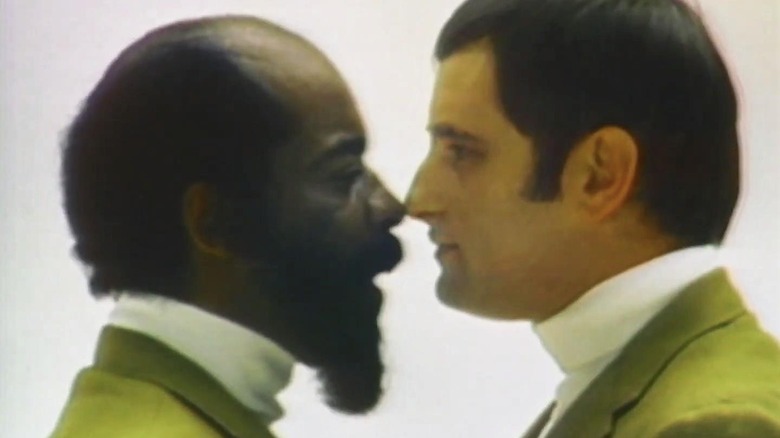

Sometimes the series addressed controversial topics, like sex or racism. In the second episode, cast member Mel Stuart was presented as the first Black member of the Supreme Court. The very Southern officiant swearing him in ended his handshake with a "Congratulations, boy." The series also regularly skewered right-wing politics. In an early skit, a right-wing politician — who opposes government-backed healthcare — announced that he preferred old-world, pioneer values ... like early death. In another sketch, a right-wing radio DJ, supporting gun rights and hating socialism, announced that someone had just been shot by a .38-calibre Communist. The guns are innocent. It's the Commies we gotta look out for. It could have been sketches like this that viewers found the most offensive.

Despite the oddness, the writers occasionally produced sketches that were legitimately funny and downright cogent. In the second episode, a man sat at a TV watching something very funny. He laughed and laughed, pointing and enjoying himself. His wife then entered the room and asked if he was ever going to turn the TV on. The television itself is the funny object, not any of the TV shows on it. The medium is the message, as McLuhan might say.

The sketches would be punctuated by abstract linking segments wherein computerized patterns or hand-drawn designs would float past the screen, accompanied by noisy, dissonant computer noises. It was, in a way, the computer laughing at itself, a self-satisfied robotic laugh track. We may not find the show funny, but the robots sure do. There was something distantly dystopian about "Turn-On."

"Turn-On" was, as mentioned, widely unavailable for years and years. It was only last month that the third episode saw the light of day.

Something to be proud of

Schlatter was interviewed in 2019 for the Hollywood Reporter podcast "Awards Chatter," and he admitted that he was still very proud of "Turn-On" despite its unpopularity. He understood that the series was ahead of its time, and recognized that it was too weird for audiences who would ordinarily be tuning into "Peyton Place," the TV series "Turn-On" pre-empted for its debut. Tim Conway even joked that the new show was called "Peyton Replace."

"Turn-On may have been one of my proudest moments. [...] The network wanted to do a show, so I said I could do one show, and I would do whatever I want. We came on the air with 'Turn-On,' and the guy in Cleveland wanted them to keep ['Peyton Place'] on. ... When he found out we were coming on the air with 'Turn-On,' he called all the stations and told them all to say they couldn't air the show. ... We were canceled all across the country one station at a time. But it was a wonderful experience — all the things we did in 'Turn-On' are now commonplace."

Schlatter had previously served as executive producer on "Rowan and Martin's Laugh-In," and stood behind the 1979 reality show "Real People." He produced comedy live shows, stand-up specials, and talk shows. He tried his hand at directing with 1976's "Norman... Is That You?" a film about a bigoted father (Red Foxx) learning to accept his gay son's queerness. It's one of those curios that purports to be progressive but falls back on a lot of regressive humor.

"Turn-On" purported to deconstruct television, but was far too odd for ... well, everyone. Whether or not one finds it funny is a matter of taste, but in 2024, everyone might find it to be a fascinating essay on the state of modern media.