What The Planet Of The Apes Movies Look Like Before Special Effects

When considering the greatest innovations in visual effects on film, there are few franchises that have done more for the medium than the rebooted "Planet of the Apes" franchise. While plenty of modern blockbusters use visual effects to create expansive worlds and larger-than-life creatures, "Rise of the Planet of the Apes" was the first to ground them in a human-animal hybrid protagonist and their emotional journey. There is simply no greater digitally-realized character than Caesar, (Andy Serkis) cinema's first-ever photorealistic leading ape and one of modern filmmaking's most complex and challenging characters.

Caesar's rise from the son of a science experiment to an exalted leader is as heartfelt as it is harrowing, a story of balanced leadership and immense sacrifice amidst turmoil and violence. The fact that all of this is built using digital, humanoid apes — not to mention some of the most seamlessly crafted digital environments films of this scale — is a testament to the talents of both an incredible cast and the many extraordinary artists at Wētā FX (formerly Wētā Digital). Their processes are meticulous but also fascinating, a blend of anthropology and art through which a single shot can take months to execute. By looking back at a scattering of scenes across the franchise's three core entries, one can get but a glimpse into how they pulled off this remarkable trilogy of cinematic achievements.

Bright Eyes escapes her cage

From the beginning, it was clear to the creative team on "Rise of the Planet of the Apes" that using real apes to tell the film's story would be impossible, as would using actors in prosthetics or suits. Instead, the team at Wētā FX used motion capture (or mocap for short), where expressions and movements are digitally recorded from sensors on a physical performer's body, blending an actor's performance into a digital transformation. This is first seen in its full glory when Bright Eyes escapes her cage at the Gen-Sys laboratory in the early moments of "Rise." Stunt performer Terry Notary, who plays "Bright Eyes," was dressed in a full mocap suit, complete with arm extensions that allow him to redistribute his body weight and fully move like an ape.

As explained in one of the film's behind-the-scenes behind-the-scenes featurettes, shots involving mocap were filmed twice: once with mocap performers and once without. This allowed the cast to perform with each other in real-time while also providing the visual effects artist with a "clean plate" of the environment so they could accurately recreate it around a digital model. In post-production, the mocap actor's in-frame performance is scrubbed out and replaced with its computer-generated ape equivalent, while the clean plate plugs any holes left behind. The result is about as close as you can get to genuine on-screen interaction with digital creations, something many films utilizing visual effects are unable to accommodate. This was only accomplished thanks to advancements in mocap technology, including suits that could be used on location and in daylight, not just on studio backlots.

Will comforts Caesar after being attacked by the neighbors

To make apes that look this good, performance capture is only half of the equation. In fact, certain ape-centered scenes in the film don't feature mocap actors at all. Take the scene pictured above, the aftermath of a hostile encounter between a small Caesar and Will's neighbor that leaves Caesar injured. This scene takes place when Caesar is still a chimp; Andy Serkis would naturally be too large for actor James Franco to hold, so the production team used a bust to get a more accurate representation of the character's physics and movement. However, this does not give the animators any direct reference to performance, so how does the character come to life?

As explained in another featurette, the team at Wētā spent many hours in pre-production studying chimpanzees, gathering data on their appearance and movements. Then, the animators began digitally constructing each species' skeletal, tissue, and muscle mapping so each model's animation would be accurately simulated from the ground-up. From there, an entirely separate team of animators would add texture, using real-life scans of skin and hair to add even more detail. There was even a special focus put on the eyes of the animals, which were essential to conveying the thoughts of each ape character. All of this attention to detail made it so that the animators could animate apes when performance capture wasn't possible. For example, one of the film's long takes features Caesar swinging and climbing through Will's home; due to the extensive acrobatics, this sequence was rendered exclusively with CGI (via Art of VFX).

Will leaves Caesar at the shelter

Though the technology displayed in "Rise" is certainly remarkable, at the heart of the film's success lies one man: Andy Serkis. Known for redefining the possibilities of motion capture through his performances as Gollum in "The Lord of the Rings" and the titular gorilla in Peter Jackson's 2005 remake of "King Kong," nobody was better suited to play Caesar. However, after witnessing his full-body commitment to the character, it becomes clear that Serkis' performance exceeds the visual effects layered on top of it. In fact, co-star James Franco notes in a studio featurette that, despite looking nothing like a chimpanzee, Serkis' behavior was so transformative that he had no trouble believing he actually was one. "He's so connected to what he's doing that...he allows my imagination to take over, [so] I really can treat him as a very intelligent chimpanzee."

In another making-of featurette, the animators cite one specific moment as pivotal to understanding the range of Serkis' performance: Caesar's shocked reaction when he realizes Will is leaving him at the animal shelter. Despite acting through a pane of glass, the full extent of Caesar's rage, sadness, and feelings of betrayal are conveyed through Serkis' impassioned performance. He contorts his face so evocatively in this scene that Wētā used it as a foundation to figure out the mechanics of rigging Serkis' facial movements onto Caesar's digital model. "We knew we had to get that scene," says animation supervisor Eric Reynolds, "and [that] if we couldn't get that scene, none of the following scenes would matter that much."

The battle for San Francisco

If there's one achievement in "Rise" that rivals the apes themselves, it's the film's climactic action sequence along the Golden Gate Bridge. Unsurprisingly, the scene was not shot on location. Instead, the sequence was filmed on an enclosed set with a recreated segment of the bridge surrounded by green screens and countless small motion capture cameras. It was, as Terry Notary describes it in a featurette, "the largest mocap volume in the world" at the time, measuring at 20 feet tall, 60 feet wide, and 300 feet long (via Art of VFX). The set could fit 80 cars, hundreds of extras, and even helicopters flying overhead. It was an unprecedented advancement in performance capture for several mocap actors to fully act out such an involved sequence in an open-air environment.

Using reference photos from both the set and the actual landmark, artists at Wētā scrubbed out the green screens in post and immersed the set inside a larger, fully digital reconstruction of the entire Golden Gate Bridge. CGI expansions included the surrounding harbor and mountains, a layer of fog, the bridge's suspensions, and even additional cars. Most notably, only seven mocap actors performed on set; animators pulled from a library of pre-recorded walk, run, and climb cycles to size up Caesar's army to 150 apes. This also increased the number of artificial reflections added to cars and car windows, a subtle addition that was essential to making the apes look authentic. Some stunts even required CGI extensions to the helicopters, meaning no on-set element went without digital expansion.

Caesar and his army attack a bear while hunting

As soon as "Dawn of the Planet of the Apes" begins, it's clear that the bar is already being raised. The trilogy's second installment begins with an intense deer hunting sequence, led by Caesar and his ape army covered in face paint. You can immediately see a greater fidelity in the faces and textures, not to mention the surrounding environment. It's a significant leap forward in the franchise's visual effects, one only Wētā could execute.

For the trilogy's second installment, Wētā's motion capture and animation teams took on several new challenges that reflected the evolution of the story. As detailed in the featurette "Dawn and Weta," the production team shot in far more intense conditions, using Vancouver as a stand-in for the forests of San Francisco. As such, Wētā used wireless motion capture cameras to avoid running cables and adapted the actors' mocap sensors to withstand heavy rain and snowfall. In addition, the characters themselves are older and have grown more intelligent due to the virus. Animators gave returning characters more weathered skin and hair textures, more pronounced facial features, and more nuanced expressions.

The opening hunt culminates in a grizzly bear attack, another wholly digital creation from Wētā. Terry Notary, returning to the series as an ape choreographer, stood in as the bear on set using a physical bear head on a stick. This gave the actors a sense of scale and spatial awareness to act off of the creature, while it gave the animators a reference point to layer on their digital model. It's yet another striking example of Wētā's seamless digital capabilities for animal characters.

Malcolm and his team return to the human colony

After a tense confrontation with Caesar, Malcolm (Jason Clarke) and his team — including his wife, Ellie (Keri Russell), and son, Alexander (Kodi Smit-McPhee) — return to their human colony nestled in the heart of San Francisco. This is our first look at the film's most extensive digital environment, an overgrown and dilapidated vision of the city in the wake of a viral pandemic. Though some photography was shot within the city's iconic locations, Wētā's VFX breakdown reveals that this version of San Francisco is actually a combination of both the real city and a set built in New Orleans (this was likely decided thanks to Louisiana's tax incentive for film productions).

Though there were some constructed sets, the majority of the city's scale is conveyed through digital extensions. The animators used LIDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) and photogrammetry, the collection of environmental data, to modify both cities to reflect their unique reality. Digital additions were added both behind and on top of Louisiana streets and buildings to reflect the taller, more mountainous cityspaces of the West Coast, and animators even looked at real skyscrapers from South America and Asia that were halted mid-construction to design many of the city's tallest structures.

Naturally, the Golden Gate Bridge once again makes an appearance via the digital model built for "Rise," as shown in an extensive studio featurette, though this time it is more rusted and overgrown. Speaking of greenery, the CGI's largest contribution was easily the amount of vines, shrubs, and trees that have spread across the city, a reflection of how nature returns to environments with less human interaction. Wētā's work is so thorough that, in some scenes, the entire city is completely digital.

Koba guns down two human soldiers

Actor Toby Kebbell had only tackled a scattering of supporting roles before playing Koba in "Dawn," a returning character from "Rise" (then portrayed by Christopher Gordon) and this sequel's primary antagonist. Though he would be thrust into the public eye after his stint as Doctor Doom in "Fantastic Four" just one year later, Kebbell's extraordinary performance in "Dawn" brought him great visibility in the film community. It's hard to match Andy Serkis and his portrayal of Caesar, but Kebbell comes real close; the dimensions he brings to Koba's unpredictable characterization and complex motivations make him one of the film's most compelling elements.

Kebbell's standout scene involves Koba tricking two human soldiers into giving him one of their rifles; he mercilessly shoots both of them shortly after. The scene required Kebbell to be disarmingly playful while also maintaining a horrifying tension. You knew that, at any moment, he could snap back into destructive ways — it was only a matter of when. Part of this tension was achieved through improvisation, which forced Wētā to put special attention on Koba's animation. "One big challenge for our team was carrying the intent of Toby's acting choices across to a very different ape physiology," explains the unnamed voiceover in this brief featurette from Wētā Digital. "Making them read clearly on Koba's large ape muscle and heavy brow required careful study of each facial expression. The hands of many artists were involved to produce...the dramatic emotional changes that make Koba so fascinating and believable."

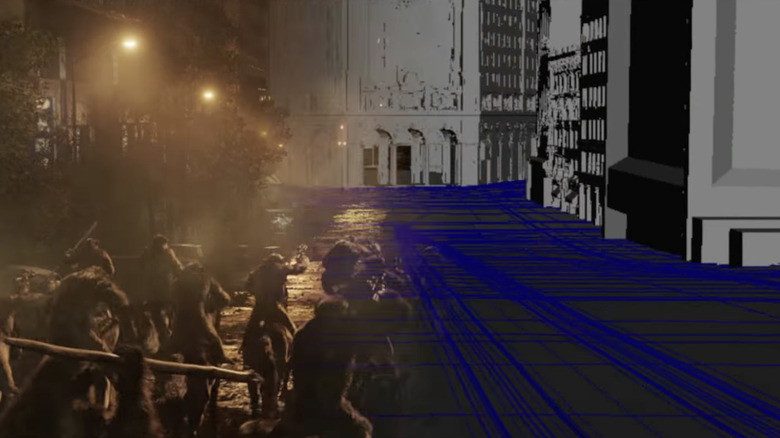

The (second) battle for San Francisco

If one outrageous battle between apes and humans in San Fran wasn't enough, "Dawn" is here to help you hit your quota. After Koba tricks his fellow primates into thinking the humans have killed Caesar and destroyed their sanctuary, all-out war commences in the heart of the city, complete with apes riding horses, wielding shotguns, and even manning tanks.

Due to the extraordinary number of apes and the absolute chaos throughout this sequence, many shots were entirely digital, including the city backdrop. Wētā breaks it down in their aforementioned aforementioned featurette, revealing that LIDAR and photogrammetry had already provided detailed, photorealistic maps of downtown San Francisco, so the animators used this as the basis to reconstruct the over mile-long stretch of city streets along which the battle takes place. In addition, they used additional satellite data to construct aerial shots of the city, which include the human colony's towering homebase.

With this digital flexibility, Wētā also had control over other elements, including flashes, smoke, and debris from firearms and explosions. Another featurette reveals that one of the film's most iconic shots, Koba leaping through a wall of fire on horseback, was accomplished digitally as well. Speaking of the apes, many of them are also digital, but so are the horses they are riding, as illustrated in a lengthy behind-the scenes featurette. The team at Wētā planned on shooting clean plates and scrubbing out the mocap riders — their traditional process — but they realized the amount of overlapping riders within a single shot would make the process too tedious. In the end, they fully animated both the apes and the horses in a feat of movie magic.

Caesar returns to his hidden fortress

It's no surprise that "War for the Planet of the Apes," the end of Caesar's trilogy, continued advancing Wētā's motion capture technology. However, the true technical highlights of the film come from the environments and climate simulation, which feel massively expanded in comparison to the previous two films. Once again, director and co-writer Matt Reeves strove to further expand the story, and the digitally created world needed to expand with it.

The first major example of this is Caesar's hidden fortress, detailed in the a Wētā featurette, a secret base shrouded by an entirely digital waterfall. This stands in stark contrast to the hydraulic dam in "Dawn," which was not only a mostly aesthetic element, but was shot practically and embellished with CGI additions. In "War," the waterfall acts as a setpiece that interacts with many characters across the film's first half, however, location scouts were unable to find a practical waterfall of the appropriate size. In response, Wētā funneled water and mist animation through their simulated physics engine to make their digital cascade feel dynamic and responsive to its environment.

Outside of one constructed blue-screen set, the fortress itself is also digital (again in opposition to "Dawn," where the ape sanctuary featured a large practical set). Another Wētā featurette shows that animators once again used LIDAR, this time to build physical models of each set that were then built digitally using overlapping rock formations and custom-grown vegetation. Animators also digitally recreated elements of production design for more flexibility in the set construction.

Caesar is captured and taken to the prison camp

The next setpiece is perhaps the film's most striking: an abandoned army base-turned-prison camp where hundreds of apes are kept in captivity while the Colonel and his army keep watch. Though the camp in the film is located in the Sierra Nevadas, keeping with the film's Californian setting, a Wētā making-of featurette details that photography took place on a 70,000 square foot set in Vancouver, British Colombia. Using 100,000 square feet of towering green screen walls, the animators were able to scrub out Vancouver's barren environment and replace it with digital mountains. While some were based on photogrammetry of California's Whitney Portal canyon, other structures were custom-built to achieve specific shot compositions.

The surrounding forest was achieved through additional simulation, though this one was quite a unique leap. Wētā used a then-newer in-house software called Totara to simulate the initial growth of a forest and 100 years of its development. According to VFX supervisor Erik Winquist, the program allowed his team "to virtually 'seed' terrain based on rules and let those seeds 'grow,' mimicking nature in the way that the various species compete for sunlight" (via Art of VFX). Using this data, Totara crafted a responsive, dynamic environment to the point that branches naturally began bending under their own weight even before snow was added on top. The result is about as close to a natural forest as you can get, all done through simulation and pre-rigged to respond to whatever additional animation would occur around it. Which leads us to...

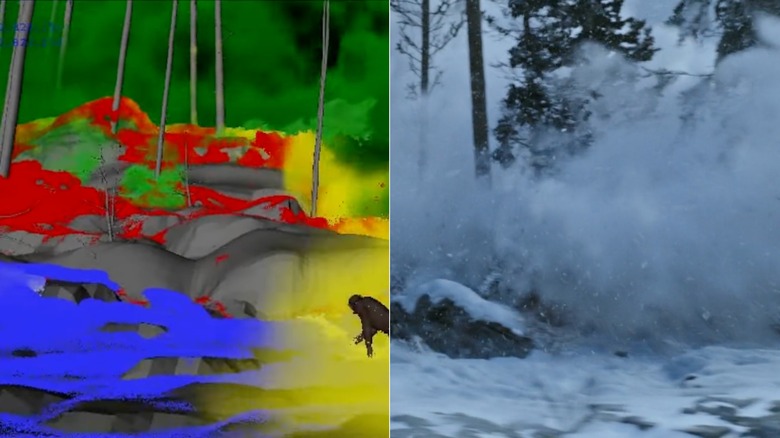

An avalanche destroys the prison camp

The film's third act prison escape is bookended by a massive avalanche, easily the grandest piece of climate simulation Wētā achieved across the entire trilogy. Snow is a prominent element throughout "War," with even the mocap suits built out further to withstand practical winter conditions (via WIRED). However, there was also extensive digital snow added to many of the film's environments, including the mountains and forest surrounding the prison camp.

Of course, the majority of it is seen rushing down the mountain in the film's simulated avalanche, as illustrated by this Wētā's VFX featurette, which was run through countless programs and software to realistically portray every element of the disaster's physics: the speed at which the snow fell, how the amount of snow built from the avalanche's momentum, how the prison camp would be incrementally destroyed, etc. Thanks to Totara, the forest was already prepared to respond dynamically to the avalanche's impact.

However, according to Wētā, the real challenge was manipulating all of these realistic effects to still convey stakes and story beats. The curve of the avalanche was designed specifically so that certain shots could be achieved, such as one in which Caesar runs across the rocks as the avalanche stays consistently close to his feet, increasing the tension.

Wētā's extraordinary ability to balance naturalism and manipulation reaches its peak during this sequence, making it the perfect way to cap off a trilogy that was built off of that ability from the very beginning.