Directors Martin Scorsese And Steven Spielberg Debunk One Of The Biggest Myths About Schindler's List

When you work in Hollywood, but can't write or direct or act or do anything that requires a practical skill ... well, you're either an executive or an agent. This means you probably make more money than most of your clients or the genuinely talented people you employ. This, you'd think, would be enough to get you through the night. But these are (mostly) awful people with awfully large egos. They don't just want money. They want credit for having played (they believe) a vital part in the creation of art. So they exaggerate their role to anyone who will listen (hopefully a credulous reporter). And when that's not enough, sometimes they just flat-out lie.

Erstwhile superagent Michael Ovitz played this mendacious game better than anyone.

As the chairman of Creative Artists Agency in the 1980s and '90s, Ovitz was the most feared/desired man in Hollywood. His client list was a list of the most sought-after actors and directors in town. If you were a big name and he didn't rep you, you could be sure he was covertly angling to remedy that. Stories about his ruthless deal-making acumen were legion — which was odd because he famously loathed publicity. Who, then, was spreading the legend of Ovitz? Not his enemies and certainly not his proteges (who lived in fear of cheesing him off). It was quite the mystery!

Once the facade cracked and Ovitz had to start granting more interviews to rebuild his badly damaged reputation, the world began to realize there was no bigger a believer in the genius of Michael Ovitz than Michael Ovitz himself — and by the early 2000s, he was probably the only believer left. Now that he was out of power, all he had left were the stories of his glory days. Some of these stories have been told so many times, they became unchallenged facts. So it's nice when you can get two immensely respected artists to go on record and dispel Ovitz's BS.

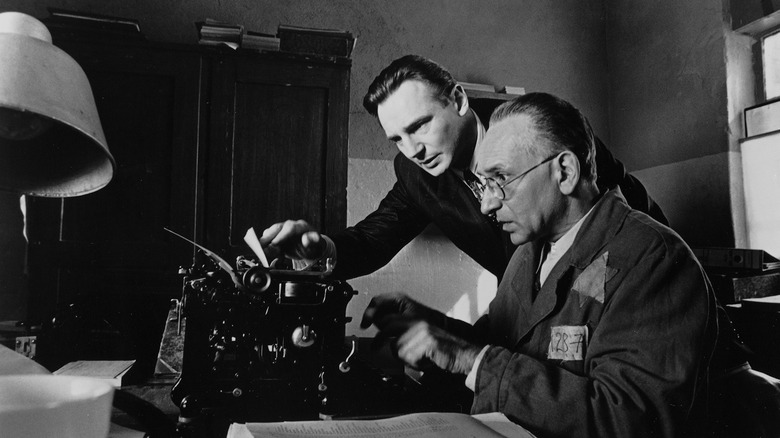

Scorsese needed a hit and Spielberg wanted an Oscar

The short version of this particular story goes something like this: in the late 1980s/early 1990s, Steven Spielberg was hot to make a film adaptation of Thomas Keneally's book "Schindler's Ark." Alas, the director's film-brat buddy Martin Scorsese was attached to the project with screenwriter Steven Zaillian. Eventually, a deal was struck that resulted in Spielberg trading his in-development remake of J. Lee Thompson's noir thriller "Cape Fear" to Scorsese (who badly needed a commercial hit) in exchange for the Keneally project. Both films wound up being hits, with the latter earning Spielberg his first Oscars for Best Picture and Best Director. A bigger return for Spielberg, to be sure, but generally a win-win.

We've been hearing this story since both films got made, and there's never, to my knowledge, been any significant push-back on its veracity. I've written about these movies many times, and have repeated this tale as apparent fact myself. And in The Hollywood Reporter's recently published oral history of the making of "Schindler's List," Ovitz is still insisting this is how it went down.

As he told THR:

"One of the biggest things with Marty — and I started handling him in 1979 — was that Marty never cared about money, but he had to live. One of the things I tried to do for him was get him to make not just passion projects but projects that he was passionate about that would also have wider audience appeal."

We agreed on a swap

Ovitz spied that potential project in "Cape Fear," which also gave the calculating agent an in to Spielberg, whom he was eager to sign. Ovitz pitched it to Scorsese as a box-office home run with artistic integrity that, not for nothing, would give him the opportunity to re-team with frequent collaborator Robert De Niro. Scorsese read Wesley Strick's screenplay, dug it, and gave Ovitz the go-ahead to broker the trade with Spielberg. Per Ovitz:

"Through a period of weeks and a lot of conversations between me and Steven, me and Marty, and Marty and Steven, we agreed on a swap: Steven would give Marty 'Cape Fear' and executive produce it, which would help from the standpoint of audience appeal; and Marty would give Steven all the work he did on 'Schindler's,' plus the underlying rights. We closed that deal verbally, all shook hands, and then the hard part began."

Over 30 years later, the hard part for Spielberg and Scorsese is buying Ovitz's version of events.

There was never a trade

After Ovitz's spoken paragraph of self-aggrandizement, Spielberg swings in with a terse refutation. "I would never have done that. Marty would never have done that. There was never a trade."

As for what really went down, Scorsese provides a little more detail.

"'Cape Fear' was payback," he says. "The payback at that time was for ['Last Temptation of Christ']." Scorsese's adaptation of Nikos Kazantzakis' novel was a lightning rod for controversy with devout Christians upon its release in 1988, and the backlash had anti-semitic overtones (given that the studio was run at the time by Jewish executive Lew Wasserman). While Scorsese felt confident defending a film that was in part an exploration of his own Catholic faith, he was worried that he'd be out of his depth handling a project about a gentile industrialist saving Jews during the Holocaust.

"...[B]y the end of it, I felt that if there was any controversy that would come up, I didn't know if I could've stood my ground in terms of who the man [Schindler] was. I didn't want to do more harm to the Jewish community. I knew it was Steve's passion project for many years. So I gave it back."

Several decades on, Scorsese has no regrets.

"[Universal] allowed 'Last Temptation' to happen ... So I helped them with the 'Schindler' thing and I did 'Cape Fear' and 'Casino.' As Mike Ovitz told me, 'They'll get this picture ['Last Temptation'] made for you, but they're going to want that pound of flesh.' So I gave them flesh — I lost some weight."

And we got three fantastic movies from two masters with a whole lot less involvement from Ovitz than he'd like you to believe. It wasn't a trade. It was just an extraordinarily convenient situation where two filmmakers were able to do what was best for themselves and the material.