Can A Film Ever Win All Four Acting Oscars? An Investigation

(Welcome to Did They Get It Right?, a series where we look at Oscars categories from yesteryear and examine whether the Academy's winners stand the test of time.)

With all the milestones that have occurred throughout the 95-year history of the Academy Awards, there are still plenty of accomplishments that have not transpired. No Black woman has ever been nominated for Best Director, and no Black person has ever won that category. No animated film has ever won Best Picture, and no documentary has ever been nominated. I do believe all of these things will eventually happen in the future. As the diversity of the industry steadily increases and Academy membership gradually expands, these sorts of things must happen as time moves on.

But there is one thing I remain skeptical about when it comes to Oscars milestones. It has nothing to do with representation, nor does it have to do with under-appreciated genres or mediums. This particular milestone would simply be a show of pure dominance at the ceremony. To this day, no film in history has ever won all four acting awards at the Oscars. Only three films have come inches away from achieving it: Eliza Kazan's "A Streetcar Named Desire," Sidney Lumet's "Network," and last year's "Everything Everywhere All at Once," from Daniels. Each of these movies won three out of the four acting prizes, but none could pull out the full sweep.

I want to use these three movies as case studies and see if any of them actually had a fighting chance to win all four races. Maybe they could provide a blueprint for how a future film could actually do the seemingly impossible, and if no movie can, what is preventing it from happening?

The case of A Streetcar Named Desire

The first film to ever win three acting Oscars, the screen adaptation of Tennessee Williams' seminal classic "A Streetcar Named Desire," I believe also had the best chance for a picture to win all four. "Streetcar" is designed nearly to be a four-hander, and each of the four primary characters are given big parts for each of them to sink their teeth into, which is something the Academy loves. When the Oscars came around, they were able to take home Best Actress for Vivien Leigh, Best Supporting Actor for Karl Malden, and Best Supporting Actress for Kim Hunter, which wasn't a foregone conclusion. Leigh won prizes like Best Actress at the Venice International Film Festival, but lost at the Golden Globes and New York Film Critics Circle. Hunter did win the Golden Globe, but there were very few precursors for supporting categories back then. Malden won nothing prior to the Oscars.

Famously, the category it ended up losing was Best Actor for Marlon Brando's now legendary, medium-shifting performance as Stanley Kowalski, which happened for a couple of different reasons. Most notably, Humphrey Bogart was due for an Oscar, and his performance as the drunkard ship captain in "The African Queen" was a perfect opportunity to recognize the star. Almost as crucial, though, was that what Brando does in "A Streetcar Named Desire" was so out of the ordinary with what screen acting was at that time, taking a hard pivot away from the traditional, presentational method of performance. For some, it was revelatory. For others, it was alienating. Had people more familiarity with the Method prior, I think he would've fared better. It's how he won three years later for "On the Waterfront." Alas, the dream of the four-for-four was foiled.

The case of Network

25 years after "A Streetcar Named Desire," we have "Network." While not adapted from a play, we few people write more theatrically than Paddy Chayefsky, and this film is packed to the brim with performances of people giving towering monologues where each one is more riveting than the last. Peter Finch won Best Actor (posthumously beating out his co-star William Holden), Faye Dunaway took home Best Actress, and Beatrice Straight was awarded Best Supporting Actress, which still holds the record for the performance to win with the shortest amount of screen time at just a little over five minutes.

"Network" received five acting nominations, but vote splitting obviously didn't come into effect because Finch won. The stumbling block for "Network" was Best Supporting Actor, where Ned Beatty lost to Jason Robards for "All the President's Men." The 49th Academy Awards is a legendarily great year, and Best Supporting Actor is one of the most competitive categories, with Robards also beating out Burgess Meredith and Burt Young for "Rocky" and Laurence Olivier for "Marathon Man," who won the Golden Globe.

I believe Ned Beatty was running in fifth place for his mere six minutes of screen time in "Network." That briefness was a boost for Beatrice Straight, but her big scene is driven entirely by raw emotion, which stands in such stark contrast from the film's general grandstanding. Beatty's performance is the most grandstanding of the bunch, as he lays out the frightening, cynical way that corporations run the world. Robards has the space to be both avuncular and gruff, and ultimately, he holds the core thematic principle of "All the President's Men" in his hand. Had Robert Duvall been nominated for "Network" instead of Beatty here, I think the chances of going four-for-four would've been stronger.

The case of Everything Everywhere All at Once

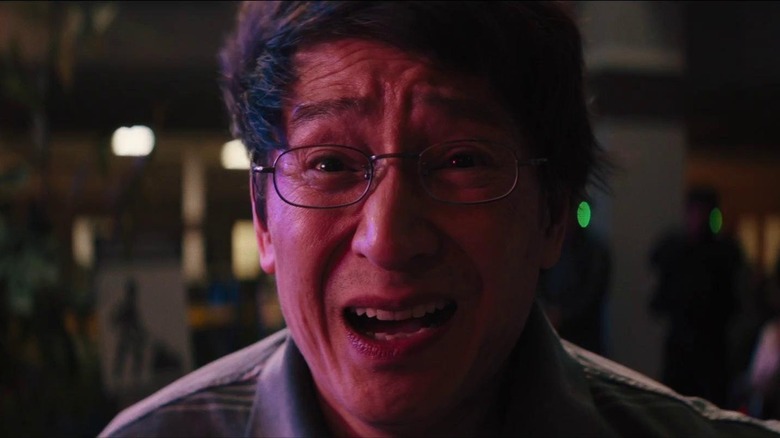

The most recent film to take home three Academy Awards for acting also happens to come from the most recent Academy Awards, with "Everything Everywhere All at Once." Notably, this is also the only film of the three to also win Best Picture along with the acting prizes, whereas "A Streetcar Named Desire" and "Network" only won one other award apiece (Best Black-and-White Art Direction and Best Original Screenplay, respectively). "Everything Everywhere All at Once" dominated with seven wins across its 11 nominations, which included wins in the same three categories as "Streetcar." Michelle Yeoh, Ke Huy Quan, and Jamie Lee Curtis won Best Actress, Supporting Actor, and Supporting Actress, respectively.

So, if the film clearly had such widespread support amongst the Academy, why couldn't this be the film that broke the barrier and won all four? Well, it comes down simply to the fact that "Everything Everywhere All at Once" does not feature a leading male character and consequently was not eligible in Best Actor, which ultimately went to Brendan Fraser for "The Whale." The story of this film clearly rests on the shoulders of Michelle Yeoh, and no matter how poignant you find Ke Huy Quan's work in the film, there's no scenario in which you justify bumping him up to lead status. Even if you did, it would be even more difficult to justify giving that slot to James Hong, let alone the win. When you have a film with a singular protagonist, the chances of you pulling off this (so far) unachievable feat are automatically zero, even if the Academy adores your movie at large. That isn't a mark against the movie. That's just how the Oscars operate.

Finding four Oscar-friendly roles

The biggest hurdle movies have to clear at the Oscars for this to even be a distant possibility is that most films, by and large, focus on one main character, like "Everything Everywhere All at Once." Subjectivity in narrative storytelling is such an important factor, and there's no better way of achieving that subjectivity than by telling a story primarily through the eyes of a single figure, and everyone else in the film is there to either act as a friend or foil to that figure.

When it comes to winning awards, having an entire movie catered to that one figure makes voting for the performances as those figures far more appealing. That is partly why biopics do so well in the lead acting categories. Tracking the emotional and psychological arc of one person over two hours gives that performer many different colors to play to showcase their range. Splitting time with a co-lead may give you a great scene partner, but it also gives you a competitor in the voters' eyes, which decreases the likelihood of you both winning.

Only 15 movies have ever been nominated in all four acting categories, and just two have managed to win both lead categories: "Network" and "Coming Home." In seven others, one of the two leads won, and in every case, it was Best Actress. These female roles are generally more explosive than their male counterparts, and I think that gives the perception that they win the movie. The women are awarded, and I believe the men all lose because of a backward subconscious belief that these men let these women walk all over them. You see the same correlation in supporting, too, with zero lone Supporting Actor winners. Identifying a film with four Oscar-friendly roles is no picnic.

Should any movie have won all four acting Oscars?

Whenever I write a "Did They Get It Right?" piece, I always put myself in the position of an Oscar voter and tell you what I would have nominated or given the award to. Most of the time, my winners and nominees are perfectly clear in my head. You'd think I would have the film that I believe should've won all four acting races. There must be a film out there the Academy just completely whiffed on that deserved to sweep those categories.

Pouring over my personal ballots from the first year of the Oscars to the present, I cannot find a film that I think should have won all four prizes. There are plenty I could find where I would strongly support nominations across the board, as well as a couple of wins, but not the sweep. Even my favorite film of all time — Billy Wilder's "The Apartment" — couldn't do it. The closest I came was "The Exorcist," where I tried to justify to myself giving Ellen Burstyn, Jason Miller, Linda Blair, and Max von Sydow the awards. Had that happened, it would have been very cool, but on my personal ballot, only Blair wins Best Supporting Actress (which is kind of category fraud).

Ultimately, I think the stars will never align for a film to win all four acting Oscars. You need an increasingly diversified voting body to choose a film that is widely Academy-friendly with four juicy parts played by top-tier talent in a year where there's zero desire to spread the wealth amongst weak competition, while also eliminating any other narrative factors that win people Oscars. Plus, there's always the future possibility of eliminating gendered categories. It's damn near impossible, but I'd love to see it happen.