Paranormal Activity's Box Office Profits Paved The Road To Five Nights At Freddy's

(Welcome to Tales from the Box Office, our column that examines box office miracles, disasters, and everything in between, as well as what we can learn from them.)

Horror movies might be snubbed by snobs and ignored by the Oscars, but they've never gone out of fashion for one simple reason: horror makes money. Other genres, from westerns to rom-coms, have risen and fallen at the box office, but horror is the true final girl of cinema. That's a lesson that Blumhouse Productions founder Jason Blum took to heart after "Paranormal Activity" became the most profitable horror movie of all time, building his studio up around a model of producing low-budget horror movies with massive returns at the box office.

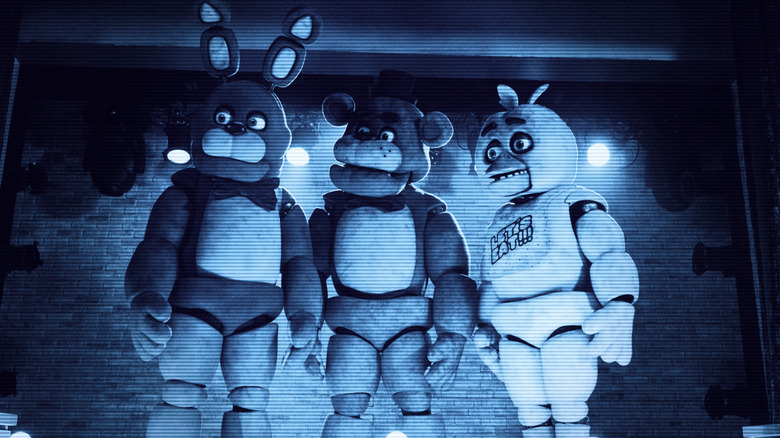

It's a model that has taken Blumhouse from strength to strength over the last decade, and yet Blum still had doubters when he set his sights on an adaptation of horror game franchise "Five Nights at Freddy's," which is heading for a record-breaking $78 million opening weekend despite a day-and-date streaming release on Peacock. "Everyone said we could never get the movie done, including, by the way, internally in my company," Blum told IGN in a recent interview. "I was made fun of for pursuing this."

As Blumhouse celebrates its 19th movie opening in the No. 1 spot at the box office, let's take a look back at the monster success of "Paranormal Activity" and how it launched Blumhouse into becoming Hollywood's most successful horror studio.

The movie: Paranormal Activity

"By trade, I am a software programmer, so I never really had any experience with movies before" Oren Peli told Moviefone in 2009. "I never even made shorts or anything like that."

The idea for "Paranormal Activity" began when Peli moved from his apartment into a detached house in "a very quiet, suburban neighborhood." He'd been used to hearing the sounds of his neighbors through the walls, so the silence of the suburbs drew his attention to every little sound in the house. "I'm sure most of it was natural sounds of the house settling," said Peli. "But every once in a while you would hear things that would be weird and you couldn't figure out where they are."

Peli got the idea of setting up cameras around the house to try and catch whatever was making the noises, and that idea became the premise for "Paranormal Activity." It was shot in Peli's own home, with a crew made up of Peli himself (as screenwriter, director, cinematographer, editor, and set decorator), his best friend since childhood, Amir Zbeda, and Peli's then-girlfriend, Toni Taylor, who became "a reluctant helper" since the film was, after all, being shot in her home. Peli also hired a make-up artist, Crystal Cartwright, since make-up was the only thing he couldn't figure out how to do himself. The core cast was made up of just two actors: Katie Featherston and Micah Sloat.

The film was shot on a production budget of around $15,000, though beforehand Peli spent upwards of $30,000 renovating the house to be suitable for a haunting. Most of that went on replacing carpeted floors with hardwood floors ("Hardwood floors are easier to slide things or people on," he explained in an interview with the New York Times).

Getting to the big screen

Peli premiered his movie at Screamfest Film Festival in 2007, where it was seen by an assistant at Creative Artists Agency. CAA signed Peli and began sending out DVD copies of the movie, searching for a distributor. Per the LA Times, one of the people who got a copy of the DVD was Steven Schneider, Jason Blum's producing partner. Blum and Schneider began working with Peli to find a home for the movie, eventually making headway at DreamWorks and managing to get a DVD into the hands of one Steven Spielberg.

As Peli recounted to Digital Spy, Spielberg watched "Paranormal Activity" at his home in the Pacific Palisades, and then something spooky happened. "He tried to get back to his bedroom and somehow it was locked from the inside. There was no other way to get in and a locksmith couldn't open it. He cut through the door with a saw and sent the movie back" (in a garbage bag, according to the LA Times). "He didn't want the DVD in his house."

The film's journey to the big screen was delayed further by Paramount Pictures' acquisition of DreamWorks, but it eventually got a theatrical release planned out for fall 2009. In the lead-up to this release it returned to the film festival circuit, quickly building up audience buzz and garnering rave reviews from horror hounds. Paramount organized a tour of midnight preview screenings and installed cameras in the theaters to catch audience reactions. Those reactions formed the basis of the movie's trailer, which not only promised huge scares but emphasized the thrills of experiencing horror on the big screen. "Paranormal Activity" was primed for takeoff, and take off it did.

The financial journey

"Five Nights at Freddy's" has landed with a bang in 3,675 theaters on its opening weekend, but the success of "Paranormal Activity" was more of an avalanche. It began playing in only a dozen theaters and ramped up the number of locations every week, even inviting horror fans to request a showing in their town through a service called Eventful. The word-of-mouth publicity grew as the movie's availability bloomed, reaching 760 theaters in mid-October and hitting No. 1 on the box office charts a week later, when it expanded to 1,945 locations.

By the time "Paranormal Activity" left theaters, almost four months after its rollout first began, it had grossed $193.3 million. Not bad for a movie made for next to nothing (plus the cost of some hardwood floors).

Blum had discovered a goldmine, and quickly capitalized on it. A sequel, "Paranormal Activity 2," was released just one year after the first movie, made for a drastically increased (though still very conservative) budget of $3 million, with Todd Williams taking over directing duties and Peli stepping back into a producer role. Blumhouse's first super-profitable horror franchise was born. To date, the "Paranormal Activity" movies have grossed $890 million worldwide.

The lessons contained within

In a recent interview with Fortune magazine, Jason Blum told a story about his father. Irving Blum had been an up-and-coming young art dealer in the 1960s when he stumbled across an artist called Andy Warhol, who was painstakingly painting 32 cans of Campbell's soup cans onto canvases. Irving gave Warhol his first solo art show, and eventually bought all 32 Campbell's soup can paintings himself for a total cost of $1,000. Three decades later, he sold them to New York's Museum of Modern Art for $15 million. "'Paranormal Activity' was my soup-can moment," said Jason Blum.

Back in 2009, in the lead-up to the release of "Paranormal Activity," Blum told the LA Times that "Once every five years, a guy makes a movie for a nickel that can cross over to a broad audience. And there are about 3,000 of these movies made every year, so this film is about one in 15,000."

Many of those 15,000 movies are horror movies. Horror is a genre that rarely demands even a mid-sized budget, let alone a big budget. As Peli had proven, you can make a horror movie with just a few thousand dollars, some consumer-grade camcorders, and a handful of friends. Blumhouse followed up "Paranormal Activity" with "Insidious," a film made for just $1.5 million that ultimately grossed almost $100 million worldwide.

A crucial part of the "Blumhouse system" is high rewards not just for the studio, but for creatives as well. Blumhouse actors and directors usually work for industry minimums (around $300,000 for directors, $65,000 for lead actors) in exchange for significant back-end bonuses based on how well the movie performs. It's the same profit-sharing principal behind the very residuals that most Hollywood studios are so begrudging of that they'd rather let actors remain on strike for more than 100 days than agree to an asked-for increase. But Blum sees the model as a recipe for better, more successful movies. "[It's] betting on yourself," Blum told Fortune.

By keeping the budgets low, Blumhouse can in turn afford to make some high-risk bets. So if there's a lesson here, it's probably this: when everyone is telling you that you're an idiot to try and make a "Five Nights at Freddy's" movie, go ahead and embrace that idiocy. There's a gap in the market for it.