How M*A*S*H's Series Finale Caused A City-Wide Water Pressure Issue

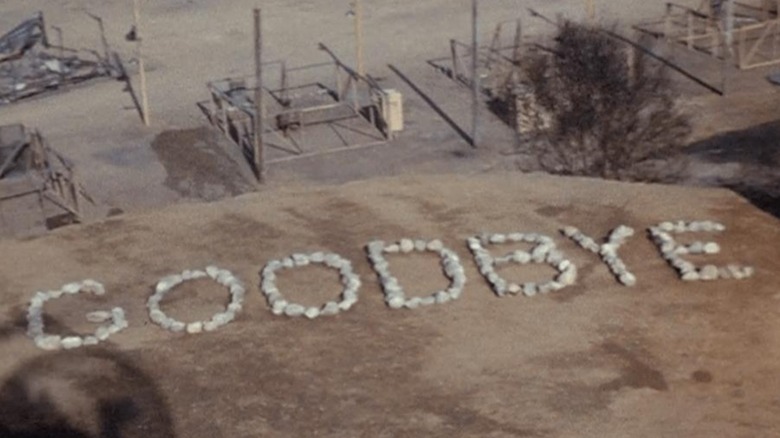

The "M*A*S*H" finale is the stuff of legends. The end of the long-running Korean War sitcom, a two-and-a-half-hour-long conclusion called "Goodbye, Farewell and Amen," aired over 40 years ago, yet it still holds space in the collective hearts and minds of Americans who witnessed it — and in the record books. Depending on how you measure it, "Goodbye, Farewell, and Amen" is either still the most-watched TV telecast of all time outside of the moon landing (over 120 million people tuned in) or one that's since been bested mostly by Super Bowls (closer to 106 million people watched the complete episode).

Either way, the show's goodbye was impressive, as are the stories that surround its nation-uniting first broadcast. In a retrospective by The Hollywood Reporter in 2018, series writer David Pollock recalled the bare streets that accompanied the show's ending. After catching an early showing for the show's crew, he says, "We drove to our favorite restaurant in Westwood. On the way, we noticed there were no cars on the street. Everyone was home watching." One Santa Rosa newspaper quoted a cable company worker noting that phones were "ringing off the hook" when 30,000 customers' telecasts cut out during the episode, interrupting watch parties at bars and houses. The show's star, Alan Alda, wrote in his book "Never Have Your Dog Stuffed" that New York's classical music radio station had a record number of callers inquiring about the title of a piece that played in the episode.

The big flush

Perhaps no anecdote measuring the success of the "M*A*S*H" finale is more pervasive — and harder to believe — than the claim that fans taking bathroom breaks at the same time caused a change in an entire city's water pressure. Executive producer, writer, and director Burt Metcalfe mentioned as much in the THR retrospective, saying:

"In New York, the only people making money that night was pizza delivery. According to the utility commission, when the show ended, there was an enormous drop in the water pressure because people were flushing their toilets at the same time. The sheer weight of it totally surprised us."

This sounds like the stuff of urban legends, and since it often bounces around the internet as a sourceless fun fact it's easy to assume the water pressure story has been debunked — but it's actually true. In Alda's memoir, he wrote that he read it in the New York Times the day after the episode, in a piece that explained that "the city's water supply was strained at every commercial break because so many hundreds of thousands of toilets were flushed at the same time."

Yet another way this show was unprecedented

A United Press International piece from the time interviewed New York Department of Environmental Protection spokesperson Peter Barrett, who said that New Yorkers used 6.7 million more gallons than usual right after the show ended. "We don't know of any instantaneous increase in water usage that would match this," Barrett said, explaining that water levels skyrocketed 3 minutes after the comedy ended and stayed high for the next half hour. A piece from the Los Angeles Herald Examiner cited in Tom Stampel's book "Storytellers to the Nation" gets even more specific, noting that DEP engineers guessed that 1 million people flushed toilets around the same time to lead to millions of additional gallons pumping through two of the city's main water mains.

While the assumption has always been that "M*A*S*H" fans desperately had to take a potty break and were waiting for the show to end, I imagine some of this water use also had to do with the amount of waterworks going on at the time. Watching the bittersweet and masterfully made "M*A*S*H" finale for the first time last year — even without experiencing the cultural context of the moment it aired firsthand — I broke my personal crying record by shedding tears a whopping nine different times. That's certainly enough to make a person want to rush to the bathroom to freshen up. Regardless, the measurements that night were unprecedented, and are a fittingly funny legacy for a show that made Americans laugh their way through countless hard times. "In speaking to engineers who've been around 30 or 40 years, they haven't encountered anything like this before," Barrett said. Super Bowls aside, it seems all too likely that there won't be anything like it ever again.