A Petty Dispute On M*A*S*H Threatened Robert Altman's Role As Director

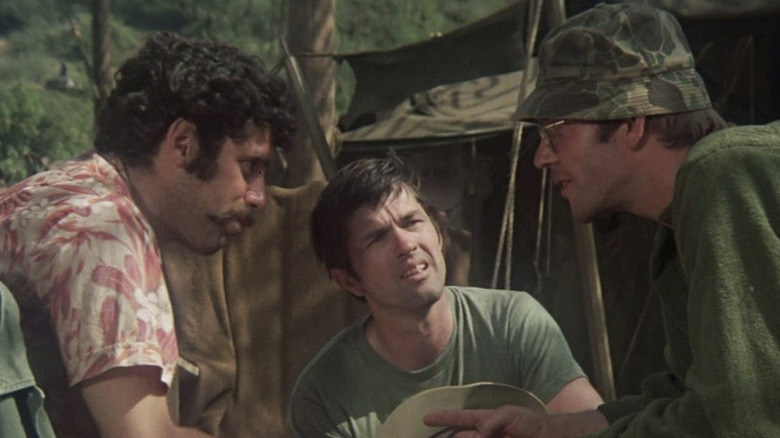

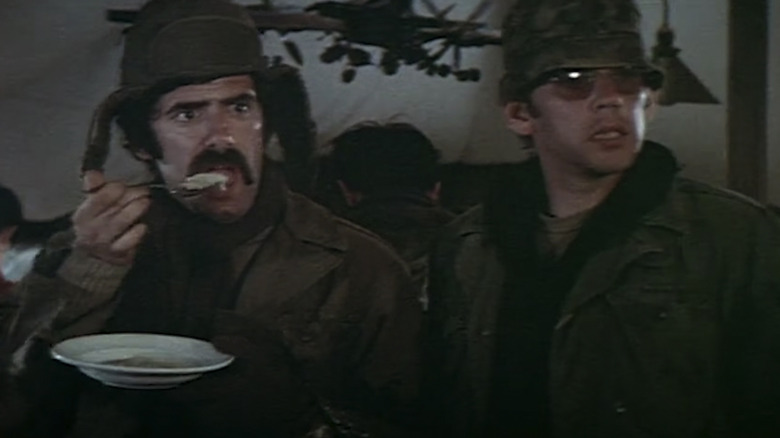

Robert Altman's "M*A*S*H" was one of the most pivotal films of the New Hollywood revolution. It approached its tale of carousing Korean War medics with a loose (one might say "stoned") counterculture sensibility. Altman, who got his start in 1950s and '60s television, filled his widescreen frame with shambling activity; actors wandered about — sometimes purposefully, occasionally confusedly — while constantly speaking over each other. This was the establishment of the shaggy Altman style, and it meshed perfectly with the politically addled times.

What it did not do, however, was agree with the film's stars.

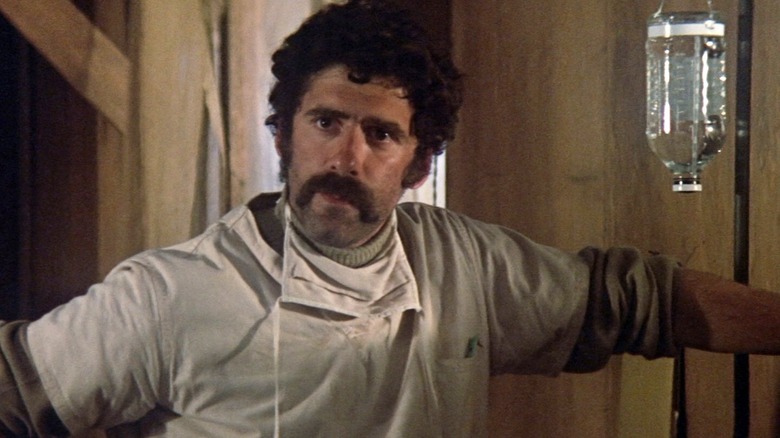

Donald Sutherland and Elliott Gould were classically trained actors. At this juncture of their careers, their preferred mode of film performing was to learn their lines, hit their marks, and, after a few months, move on to the next gig. They didn't do a lot of improvising, and had zero tolerance for being left hanging in front of the camera — primarily because they weren't big enough to protect their work in post-production. If they got stuck with a director who had no idea what he was doing, their nascent careers could be irreparably damaged.

So when they got deep into principal photography and had no idea what Altman was up to, they allegedly tried to get him fired.

'This guy is ruining our careers'

Altman's method of directing was atypical for a Hollywood movie at the time. He was noodling with his ensemble, and futzing with background players to strike what would become his signature style. This left Sutherland and Gould feeling rudderless. Why was this unproven filmmaker treating them as an on-camera afterthought?

In an interview for a behind-the-scenes doc, Altman revealed that his unconventional approach compelled his stars to approach the producers and get him jettisoned from the film. Per Altman:

"They said, 'This guy is ruining our careers,' and they said that 'He's spending all of his time talking with all of these extras and these bit players, and he's not playing a lot of attention to us.' It was kept from me. Had I known that, no question, I would have quit the picture. I couldn't have gone on knowing that there were two actors that I was dealing with that felt that way."

There are two sides to this story, however, and one of the involved parties strongly refutes Altman's account.

'That's not true at all'

In an interview for the 2014 documentary "Altman," Gould acknowledged his befuddlement with the director's approach. "I came from theater and a more conventional way of working," he said. "I don't speak for Donald, but we had a problem with it. And Bob agreed to a re-shoot. In hindsight I see it as Donald and I not really knowing or understand how Bob was working."

But did they try to get Altman fired? "That's not true at all," said Gould. "I think that Bob had had some problems or challenges with management and studios and administrators. But there was never a thought of that."

That's a good thing, too. Though Sutherland never worked with Altman again, Gould wound up making two more masterpieces with the director in "The Long Goodbye" and "California Split" (he also appeared as himself in "Nashville" and "The Player"). Gould didn't just come around on Altman, he became the filmmaker's definitive leading man; indeed, he was never better than playing a mumbling, cat-loving Philip Marlowe or a degenerate gambler who can't shake his self-destructive sickness. There wasn't a better director-star duo in the '70s. We were blessed that they found each other, and stuck it out.