Killers Of The Flower Moon Furthers One Of Martin Scorsese's Career-Long Themes

Spoilers for "Killers of the Flower Moon" follow.

Martin Scorsese is the great American filmmaker of his generation — and I don't just mean in nationality. The American Dream underpins Scorsese's films, whether unfolding in his hometown of New York City or the Oklahoma plains like his latest, "Killers of the Flower Moon." Based on David Grann's non-fiction novel, the film is set in 1920s Osage County, Oklahoma. The indigenous Osage tribe came into wealth upon discovering oil on their land — so white settlers murdered them to steal it. While ringleaders William King Hale (Robert De Niro) and Ernest Burkhart (Leonardo DiCaprio) were prosecuted, they avoided life in prison. Mollie Burkhart (Lily Gladstone), Ernest's wife and poisoning victim, dies at the age of 50 without her family, while the Osage's wealth dries up. It's hardly a victory for justice, even if the tribe refuses to be forgotten by history.

This particular setting is new territory for Scorsese (it's basically his first Western), but the themes explored are not. Scorsese's films upend the ugly reality of the American Dream. Not every striver out there can be a success story. The people who do come out ahead usually don't do so because they are the most hardworking, but because they're greedy, violent, and willing to step on others to climb ahead.

Scorsese never celebrates greed like Gordon Gekko — he's a good Catholic boy after all — but he's a realist, not a moralist. The bad guys often come out on top in his movies because that's how it works in real life, and there's never a contrived punishment to reassure the audience. In that respect, "Killers of the Flower Moon" slots neatly in with his past films.

A nobody who dreams of being a somebody

Two of my favorite Scorsese and Robert De Niro movies, 1976's "Taxi Driver" and 1982's "The King of Comedy," are companion pieces. In both films, De Niro plays an ambitious nobody who turns to violence to get what he wants.

Travis Bickle in "Taxi Driver" is an alienated and reactionary young man who feels deeply unsettled living in the urban depths of New York City. He's suggested to be a Vietnam War veteran, further adding to his characterization as someone feeling abandoned and with his back to the wall; the vacuous Senator Palantine (Leonard Harris) represents uncaring power. In the film's climax, Travis invades a pimp's den and kills three men to save child prostitute Iris (Jodie Foster). The film shows the violence in brutal detail, which makes it all the more shocking when Travis is celebrated as a hero. At the film's end, he's still a taxi driver, but not a nobody — all it took was some murder.

Then in "The King of Comedy" we have Rupert Pupkin, an aspiring comedian who really wants to appear on a late-night show hosted by his idol, Jerry Langford (Jerry Lewis). The problem is that he's not willing to work his way up and improve his craft. Rupert fantasizes about an imaginary friendship with Jerry, and even breaks into Jerry's mansion to get a taste of the high life under the delusion that his "buddy" wouldn't mind. Finally spurned, Rupert kidnaps Jerry, his demand being that he's allowed to do the opening act on an episode of Langford's show. He gets his wish and closes his routine by saying, "Better to be king for a night than a schmuck for a lifetime."

Only that's not Rupert's fate. Like Travis, he becomes a media sensation and gets the fame he always wanted, with barely any punishment.

The life of a schnook

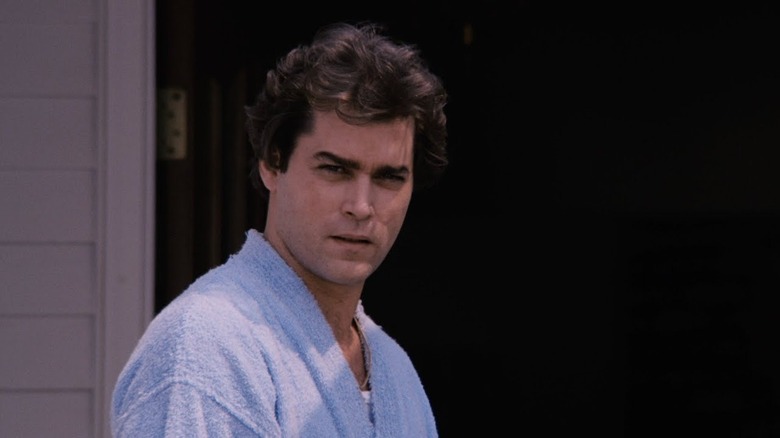

Contrary to some facile critiques, Scorsese doesn't make only gangster movies, but I think he returns to the genre again and again because he's compelled by the romanticization of outlaw. Think of Henry Hill (Ray Liotta) in "Goodfellas." Just after we meet him, he says in voiceover, "As far back as I can remember, I always wanted to be a gangster" — a perverse answer to the question asked of every American child: "What do you want to be when you grow up?"

Henry, raised across the street from a mob hangout, drops out of school in favor of spending time with his criminal pals. And yet, he still ends up living the dream: a beautiful wife (Lorraine Bracco), some kids, and a nice picket-fence house, all without the indignity of wage slavery. It's the honest workers or business owners who suffer, thanks to the mafia's "protection money" rackets and bust outs (destroying a business for the insurance money). The justice system is up for sale too; people who should be prosecuting the mafia are silent partners. The mindset of Henry and his ilk is clear: Why bother playing by the rules when cheating gets you so much further ahead?

That's why Henry's punishment isn't death or life in prison like most of the others. He testifies against his "friends," since there's no honor among thieves, and gets placed in witness protection. During the concluding scenes of the trial and Henry's new home in a bland suburb, his voiceover bitterly compares the decadent luxury he lived in as a gangster with the normality of his remaining existence. He's not feeling guilty, though; for Henry, the highs were worth the fall.

Gangster capitalism

Scorsese's post-"Goodfellas" movies focus more on how criminality and legitimate business intertwine. "The Irishman" is about the mob's infiltration of labor unions, which were one of the few honest paths for the working man to get ahead. "Casino" uses several of the same actors and crew as "Goodfellas," but jets across the country from New York to Las Vegas, where the mob takes over (you guessed it) casinos to launder money.

The film's closing montage features Ace Rothstein (De Niro) lamenting the current state of Vegas, where "the big corporations" run the town and swindle Average Joes. Corporate America as legalized gangsterism carries over in Scorsese's 2013 "The Wolf of Wall Street," about former stockbroker/convicted financial criminal Jordan Belfort (played by DiCaprio). Belfort's brokerage firm Stratton Oakmont doubles as an ongoing orgy, where the funds are supplied by fraud.

There's a scene of Jordan cold-calling and getting a $10 thousand investment on a bad stock; in between his professional sales pitch, the other brokers are laughing uproariously and Jordan is flipping the phone off, mocking his client as an easy mark. Jordan does get taken down in the end ... sort of. He spends his minimum security incarceration playing tennis like he never left his country club, and once he's out, he rebrands as a motivational speaker for the gospel of greed. FBI agent Patrick Denham (Kyle Chandler), who investigated Belfort, goes unrewarded and rides the subway home. Denham isn't Melvin Purvis bringing in John Dillinger; he's just one of the "schnooks" whom Henry Hill lambasted.

DiCaprio described Belfort's world as "intoxicating," a word with a double edge of meaning — something that draws you in, but poisons you at the same time. If you're not paying close attention, it's easy to see the ending of "Wolf of Wall Street" as a triumph, not a tragedy.

The hands that built America

America is "a nation of immigrants," but that doesn't mean those immigrants have always had an easy go of it. "Gangs of New York," set in 19th century New York City, is about the conflict between Protestant American Nationalists and Irish-Catholic immigrants. The former, led by Bill Cutting (Daniel Day-Lewis), controls the city's political machine out of Tammany Hall. When the Irish beat the rigged elections and make one of their own the city sheriff, Bill kills the man: "That, my friends, is the minority vote."

This brings us to "Killers of the Flower Moon." While the Osage's oil money is the material motive for the murders masterminded by Hale, the motive runs deeper than that. If the Osage have capital and control of their land, they're a threat to (white) American power structures. The film also notes the contemporaneous "Black Wall Street" massacre in Tulsa, Oklahoma, when thriving Black-owned businesses were destroyed by white supremacist vigilantes.

Therein also lies the reason that Scorsese finally made his Western. Such films dominated Hollywood when Scorsese came of age and vilified indigenous people as savages ("Cowboys and Indians" became synonymous with "Good guys and Bad guys"). The empathy of those films is almost always with the settlers, and the Natives are a danger to Manifest Destiny that must be overcome. "Killers of the Flower Moon" shows its Native characters as colonial victims, undone because white Americans couldn't let the Osage have even a slice of the pie.

Gangster pictures and Westerns are the most American film genres since they explore the rapacious means by which the country was built and sustained. For most people, the American Dream can and will only be a fantasy. The wolves in the picture wouldn't have it any other way.

"Killers of the Flower Moon" is playing in theaters.