What These Iconic Sci-Fi Movies Look Like Without Special Effects

Magicians conceal the techniques behind their tricks to maintain a sense of wonder and mystique. In a similar vein, early Hollywood went to great lengths to conceal the secrets of their visual effects. Both sought to preserve the magic and enchantment of their respective performances. Even when "Star Wars" came out in 1977, some news items claimed both Artoo and Threepio were actual robots.

Times have changed, and behind-the-scenes material has become commonplace. Shows like "Entertainment Tonight" and bonus features on home video all made what used to be arcane into knowledge commonplace. Does that destroy the suspension of disbelief required for a movie to be truly immersive? Given the popularity of such features, it's safe to say a significant portion of the audience doesn't think so. On some level, we know it's all make-believe.

Here's a look at what iconic science fiction films look like stripped bare of special effects; be they in-camera tricks, miniatures, matte paintings, digital set extensions, or outright CGI characters.

2001: A Space Odyssey

"2001: A Space Odyssey," directed by Stanley Kubrick and released in 1968, is renowned to this day for its groundbreaking special effects. The most iconic include the visually stunning depiction of space travel, from the "Blue Danube" waltz of spacecraft in flight to the harrowing spacewalks, and finally, the "ultimate trip" stargate sequence. But the one sequence full of visual trickery is the one no one would guess.

"The Dawn of Man" depicts an evolutionary tipping point of early human ancestors. For it, the film employed front projection on a scale never before seen. This technique involved projecting large format photographs onto a half-silvered "beamsplitter" mirror set in front of the camera. This reflected the images onto a giant screen set at the end of the set, behind the actors. This screen was composed of retro-reflective Scotchlite material, which bounces light directly back at its source.

The result: the live set and the photographic backgrounds were combined on the spot, passing through the two-way mirror and into the camera lens. The technique is betrayed by the retinas of the leopard seen in two shots: its eyes, like the Scotchlite screen, reflect the light from the projector. To anyone not directly in the path of the reflected light, all you'd see was a blank gray screen.

There's only one shot of an ape-man filmed outdoors: the iconic bone thrown into the sky, shot in a studio parking lot.

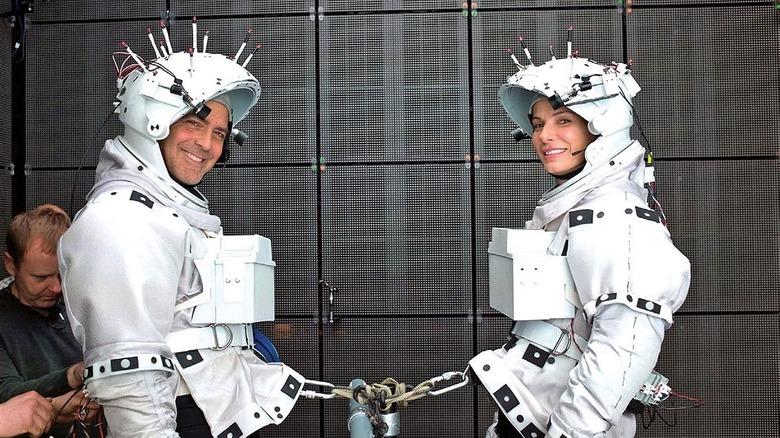

Gravity

Alfonso Cuarón's groundbreaking space thriller "Gravity" pushed the boundaries of visual effects in cinema to new heights. Released in 2013, this space odyssey took home seven Academy Awards, including one for its visual effects. Key to its success were its immersive long takes and the seamless integration of visual effects.

Cuarón originally thought to shoot the live-action scenes with actors in spacesuits against greenscreen. The limitations of that technique led the crew to devise innovative solutions. Full spacesuits proved too bulky and awkward, so simple placeholders substituted for them. The final suit exteriors were CGI creations.

Moving actors as if in microgravity was difficult, so industrial robots were used to move the camera instead. Key to selling this illusion was interactive lighting that moved around the actors as the camera moved. The "Light Box" was a structure shaped like a cube, tiled with LED panels that displayed images around the actors. This served as both a real-time visual reference and an interactive light source, allowing the actors to react to and interact with their non-existent surroundings.

Without the VFX, what you see looks rather preposterous. Actors in partial spacesuits with tracking markers stand or hang in a nine-foot square LED cube. Not so weighty that way, is it?

Forbidden Planet

"Forbidden Planet" was arguably one of the first "A" picture science fiction films. It's full of special effects, achieved by practical on-set or optical methods. Lighting, miniatures, matte paintings, and effects animation are all used. Without them, the C-57D cruiser, alien vistas, and the incredible Krell machine would not come to life.

One unnoticed effect is when Altaira (Anne Francis) calls to her tiger friend. It runs to and then walks past her, and she follows. The trick is that the actress and the tiger weren't on set together. Each filmed separately with the same camera setup, and a soft-edged split-screen matte married the two shots. If you look closely, you can see bits of the tiger are transparent when it's close to her.

A more in-your-face effect is when Jerry Farman (Jack Kelly) gets seized by the invisible Id monster, illuminated by an energy fence and a rain of blaster fire. The crew used wires to lift a stuntman into the air and illuminated him with red light. Disney's Joshua Meador completed the illusion with effects animation to depict the monster and energy effects.

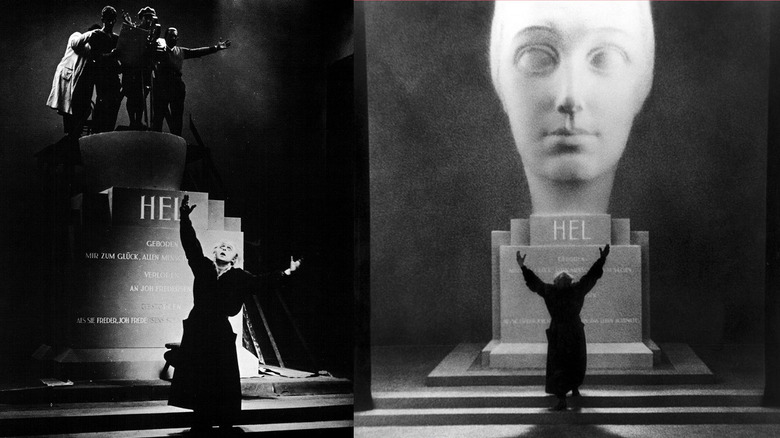

Metropolis

Pioneering filmmaker Fritz Lang's 1927 "Metropolis" is the ur-text for the science fiction epic. With a literal cast of thousands and employing fantastic special effects to portray its fractured futuristic society.

One such effect is the Schufftan Process, credited to German cinematographer Eugen Schüfftan. This early cinematic technique employed mirrors with strategically placed holes in the reflective surface. It was used to combine live-action actors with backgrounds or miniatures set perpendicular to the camera axis. This allowed the camera to capture both the reflected image and the live-action, creating a seamless integration of real actors and artificial elements.

Lang employed this process throughout "Metropolis", from the stadium to the imagined Moloch. The scale of such vistas effectively gives away that they're effects, but there are smaller scenes that employ effects that no one even notices.

One such instance is when the mad Rotwang (Rudolf Klein-Rogge) stands before a giant bust of his dead love, Hel. As on-set photos demonstrate, they built only the neck of the bust. The head itself was a two-foot-tall model added via the Schufftan process.

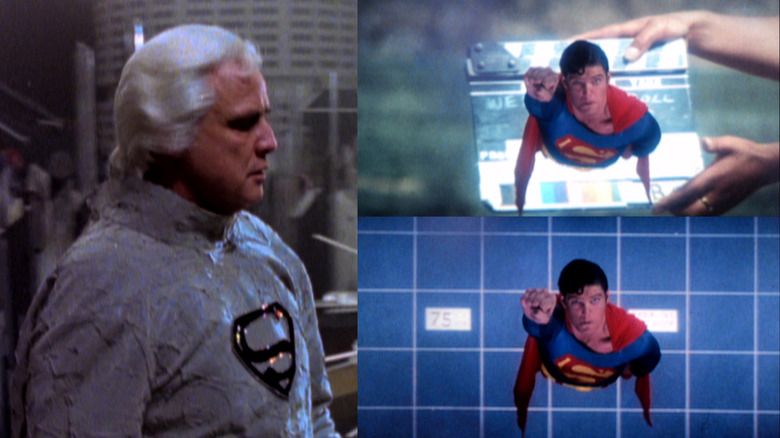

Superman

It's Christopher Reeve's physicality that sells the illusion of Superman flying, but his talent alone couldn't deliver on advertising promises that "you'll believe a man can fly." Many techniques were used to get Superman airborne. A see-saw raised and lowered Reeve on takeoffs and landings. Sometimes he'd grab a trapeze bar just out of camera view to be lifted. On the effects side, they suspended both dolls and actors on wires, and Reeve was filmed against bluescreen and matted into separately filmed backgrounds. But the primary technique for Superman in flight was Zoran Perisic's "Zoptic" system.

Zoptics was a direct descendant of the front projection process Perisic worked with on "2001: A Space Odyssey." There were three significant updates. The first was using motion picture film instead of slides for the projected backgrounds. Second was a movable rig that carried the projector, beamsplitter, and camera together as a unified package. Third was equipping the projector and the camera with synchronized zoom lenses. This allowed the camera to move towards and away from the actors without the background image changing size.

Interestingly, a simplified variation of the beamsplitter technique made the Kryptonian costumes light up. The designers made the robes of Scotchlite, but they used a simple light instead of a projector to make them glow. Superman's effects team took home a special achievement Academy Award in 1979 for their work.

Jurassic Park

Donald Gennaro's (Martin Ferrero) ignominious exit from the original "Jurassic Park" is simultaneously terrifying, humiliating, and hilarious. The T-Rex may act like a giant Jack Russell terrier, but its bite is far worse than its bark.

The Rex was depicted with various techniques, including two full-scale animatronic robots. One was 37 feet long, nose to tail. A more detailed closeup version existed only from the chest up. Neither had legs, which were a separate item. But these robotic Rexes were dangerous pieces of heavy equipment and there was no way the production would risk having one swing its massive steel-framed head down and close its hydraulically powered jaws around a real human being.

For Gennaro's demise, the Rex is a full CGI creation. Because the wind-blown plants and rain would betray any cuts, the decision was made to use a wire to yank a stuntman off the toilet as the Rex plucked him off his throne. The Rex's head, with a CGI double for Genarro in its mouth, largely obscured the stuntman's exit. This required only a tiny bit of cleanup to make the effect seamless. But, as you can see in these frames from a behind-the-scenes video, without VFX all you have is a flying stuntman and a rolling commode.

You can see how this was accomplished in a video excerpt from the "Jurassic Park" supplement, "Taming The Creatures."

The Star Wars saga

"Star Wars" movies have always been special effects epics, and the franchise's history demonstrates the evolution of effects work from the 1970s to today. So, let's focus on the saga's signature weapons and the effects used to create them.

In the original 1977 "Star Wars" (aka "A New Hope"), the glowing blades of the lightsabers were achieved live. Each "blade" was a rotating rod covered with our old friend Scotchlite. They added color and extra sizzle in post-production. The problem: the motors made the sabers unwieldy, and the beamsplitter limited the action.

Starting with "The Empire Strikes Back," retro-reflective material yielded to simple rods, with all the glowing and sparking added by effects animation. In the prequel trilogy, painted narrow tubes served as blades. In the sequel trilogy, electroluminescent material sometimes illuminated clear tubes. This provides interactive in-camera lighting, especially in dark scenes. It's been a long road from Scotchlite.

The Planet of the Apes reboot series

If you think of motion capture (or "mo-cap") as a newish thing, think again. Think back to early techniques like rotoscoping, which involved tracing live-action footage for animation. A pivotal moment in the evolution of the technology occurred in 1967 when Lee Harrison III put a dancer into an armature of Tinker Toys and potentiometers. This first "data suit" controlled a cartoon character using a human performer, and this same tech created the first mo-cap dancer. Of course, capturing coarse movement isn't enough. A mo-cap actor has to be able to project a performance through layers of digital abstraction, just as actors under heavy makeup have to act through it.

Andy Serkis is a renowned actor and motion capture pioneer known for his exceptional work in bringing digital characters to life. He came to the fore as Gollum in the "Lord of the Rings" trilogy, showing a true expertise in conveying subtle emotions and physicality using mo-cap technology. Any behind-the-scenes video of Serkis acting in his gear demonstrates how much of his performance comes through on screen, despite how silly he might look in a mo-cap suit with dots on his face. His three performances as Caesar the ape in the "Planet of the Apes" reboot trilogy say it all.

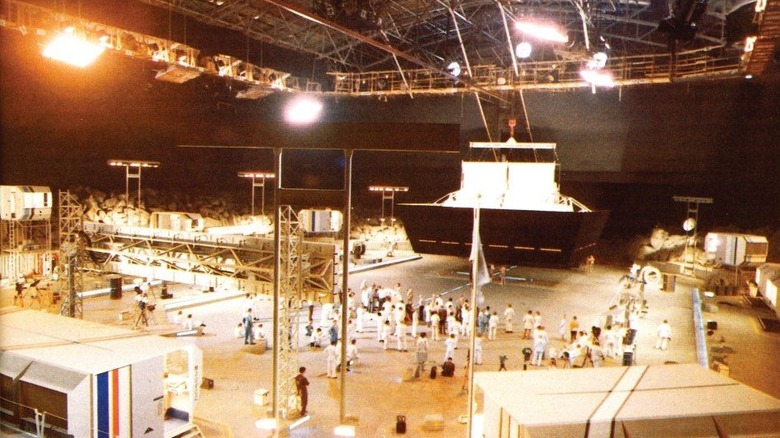

Close Encounters of the Third Kind

Steven Spielberg's "Close Encounters of the Third Kind" hit theaters six months after "Star Wars." The two actually had very little in common, aside from being special effects extravaganzas. "Star Wars" is more widely praised for its innovations, but from a technical standpoint, Spielberg's film was hands down the more elaborate. Flying ships against the darkness of space or over a mechanized battle station is one thing. Depicting glowing flying saucers in familiar earthly surroundings, that's another thing entirely.

The pioneering effects work in "Close Encounters" included filming glowing miniatures in smoke to simulate atmospheric haze, and the first use of motion control on a live film set. Camera action recorded on-set was later duplicated at VFX wizard Douglas Trumbull's effects studio to match the model photography to it.

The results were truly eye-popping. But, sans those inventive special effects, the magic is missing. Case in point: the base where the alien Mothership makes its grand appearance. Minus the effects depicting the vast dome of the ship's underside, all we're left with is a big black box.

The Matrix

The signature special effect of "The Matrix" series is what the first film's script calls "bullet time." While the Wachowskis certainly popularized this technique with "The Matrix," they didn't actually invent it. The Time-Slice camera was first devised in 1980 by Tim Macmillan, who produced a number of films with it. Perhaps the first commercial use of the technique — albeit in crude form — was Accept's 1985 music video "Midnight Mover," in which the viewpoint spins around the band at different rates. Only ten cameras were used for the effect, which resulted in a staccato look. In the '90s, TV commercials got into the act, notably the Gap Khaki Swing ad in 1998. In the year that followed, Time-Slice featured briefly in the movies "Lost In Space" and "Wing Commander."

The Time-Slice's innovation was its ability to photograph multiple viewpoints either simultaneously or sequentially at various rates. The result: the camera viewpoint moves around a scene that's either in frozen or slowed time.

But "The Matrix" pushed the effect to another level, employing up to 99 cameras to allow the viewpoint to smoothly swing around the figures. In behind-the-scenes photos you can see the lenses of some of the cameras which made the magic possible.

Jurassic World

The original "Jurassic Park" was a CGI milestone, but the actual number of shots using that technique was relatively small: fewer than 60, comprising under a third of all dinosaur screen time. Over the years the franchise has utilized more CGI and fewer practical effects like animatronics, puppets, and people in dinosaur costumes. By the time Colin Trevorrow's "Jurassic World" roared into theaters in 2015, the number of CGI shots numbered over 2000.

Fully CGI creatures are certainly cheaper to fabricate than full-scale animatronic ones. But actors famously hate performing to nothing, and many strategies are employed to provide their eyelines for the missing dinosaurs. These include poles with markers at their apex, and sometimes, even a rigid sculpt of a dinosaur head that's puppeteered for them to react to, as when Owen Grady (Chris Pratt) removes the camera strap from raptor Blue's head. It looks silly without the special effects.

If you want to see how the entire climactic sequence from "Jurassic World" plays minus any CGI dinosaurs or other visual effects, check out this video from the official "Jurassic World" YouTube channel.

Dune (1984)

An effects milestone David Lynch's "Dune" is not. Its effects range from the realistic to the wretched. Its iconic sandworms are only convincing in a couple of moments, and most of the shots of aircraft and spacecraft are clunky or look like animation.

One place it excels is in its use of the ageless hanging miniature technique, or "cutting piece." A small-scale model is suspended between the camera and a live-action set beyond it. The 1925 "Ben Hur" featured a full-size Circus Maximus arena, but in front of and above it was a miniature of the spectators' gallery.

To realize the palace at Arrakeen, the "Dune" production placed actors on a staircase set in the parking lot at Estadio Azteca Stadium in Mexico City. For a broad establishing shot, a large platform 1,000 feet away held a miniature of the city, cliffs, and wall. They placed the camera 16 feet from the model, which was designed with a gap through which the distant stairs and people on it were visible. The same technique was used to place the Atreides at the foot of their space cruiser and depict invading Sardauker troops rushing out from a Harkonnen ship.

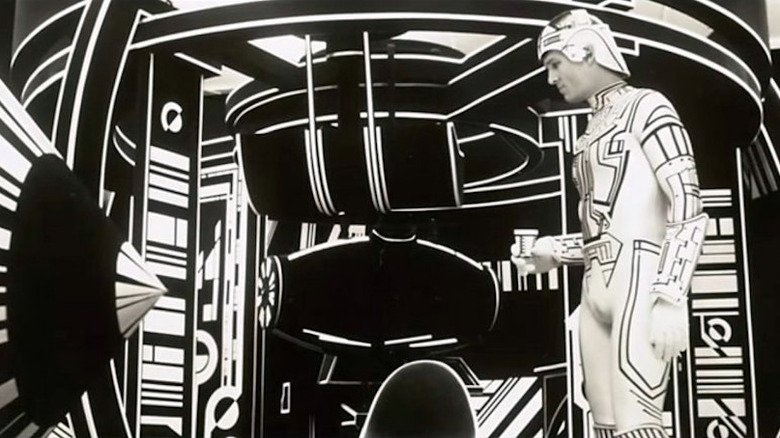

Tron

Early in the development of "Tron," production artist Andrew Probert suggested the equivalent of "bullet time" for the scene in which Flynn gets digitized, with his coffee suspended in the air as the camera circles. But this idea got no traction, and "Tron" is mostly known as the first feature film to showcase CGI in more than a scene or two.

"Tron" actually features only about nine minutes of CGI. The rest of its computer world is airbrushed artwork and animation effects. And while mo-cap existed in a fairly early state, the computers of the time weren't up to rendering the complex geometry of so many characters, let alone making them relatable. CGI was rationed for the things only it could do.

The bulk of the digital world scenes were filmed with actors in white costumes with black details against either black backgrounds or on crude sets with white details painted on. Each frame of the selected takes was printed to large high-contrast Kodalith animation cels, with hand-rotoscoped color separation mattes, all of which were shot on animation stands and composited together. The result was certainly eye-popping, but the manual work required was off the charts — just check out how many names are in the end credits. The labor-intensive process and advances in technology meant "Tron" was a one-of-a-kind production, never to be repeated.

Avatar: The Way of Water

James Cameron has a deep passion for aquatic exploration. His interest in underwater adventure has led him to embark on several groundbreaking expeditions, including the first solo descent to the Mariana Trench, Earth's deepest known point. Of course, this interest has also inspired his filmmaking — both "The Abyss" and "Titanic" incorporate his love for the sea and marine sciences.

Since most of the world of Pandora in the "Avatar" movies gets created virtually, you might think the crew would mo-cap all the underwater action dry-for-wet. Using flying rigs from superhero films along with moving camera techniques similar to those employed in "Gravity" may seem logical.

But this is James Cameron we're talking about, and he insisted the characters in should move believably in all environments. Such verisimilitude required mo-cap to be performed in water tanks. To make this possible, the cast had to train extensively to control their breathing so their performances could be captured underwater. The top actor in breath control was Kate Winslet, who at one point held her breath for an incredible seven minutes and fifteen seconds.