Why Making Star Trek: The Next Generation's Most Famous Episode Was So Painful For Patrick Stewart

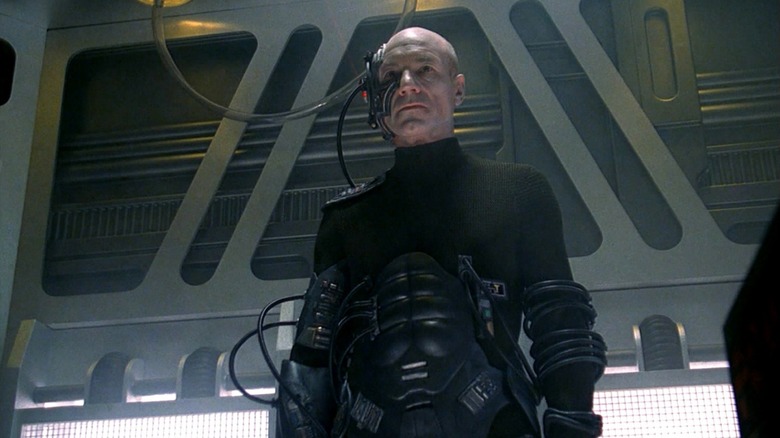

The "Star Trek: The Next Generation" episode "The Best of Both Worlds" was a banner event in the "Star Trek" world. The first part aired on June 18, 1990, and it ended on a doozy of a cliffhanger. Captain Picard (Patrick Stewart) had been kidnapped by a species of malevolent cyborgs called the Borg and assimilated into their mechanical collective. His body was implanted with machinery and tubing and his individuality was erased. In the episode's final scene, the now-assimilated Picard, calling itself Locutus, announced to his former ship, the U.S.S. Enterprise, that all its crewmembers would also be assimilated into the Borg and that the ship would be cannibalized. The Borg seemingly had no mandates other than to mechanically absorb anything they came across. The final line of the episode was Captain Riker (Jonathan Frakes), Picard's first officer for three years, ordering that the Enterprise fire weapons upon Locutus.

Fade out. "To Be Continued ..." Trekkies would have to wait until September 24 to see the conclusion. The cliffhanger was so formative that "Star Trek" has revisited it on TV and in film several times in the ensuing years. Even the 2023 series finale of "Star Trek: Picard" harkened back to this moment.

As it happens, filming "The Best of Both Worlds" was difficult for Stewart, and not just because of the elaborate Borg makeup. In addition to spending four hours in a makeup chair to apply the machines to Stewart's face and head, the actor also began to see his personal plight as mirroring that of Picard's. In both fiction and reality, a person saw themselves being swallowed up by a machine. Stewart explained why in his new autobiography, "Making It So: A Memoir."

The physical pain

Stewart was one of the few "Next Generation" actors who didn't require makeup or a prosthesis. Brent Spiner needed to be painted white and to wear contact lenses to play Data, LeVar Buton was required to wear a vision-obscuring device over his eyes to play Geordi La Forge, Marina Sirtis needed black eyes to play Counselor Troi, and Michael Dorn needed a prosthetic forehead to play Worf. Everybody wants prosthetic foreheads on their real heads. Well, everybody but Stewart, who played a human. The makeup job for Locutus was long and uncomfortable, and Stewart wrote that he suddenly understood Dorn that much better:

"The process of attaching all of Locutus's prosthetics to my head and body took about three hours, and their removal at the end of the day another hour; now I understood why Michael Dorn, despite his congenital good cheer, often looked so miserable."

But the physical discomfort wasn't as hard for Stewart as the emotional discomfort. Stewart had been acting on "Star Trek" for three years, a job that prevented him from appearing in extended stage productions as he might have preferred. Indeed, Stewart began to see "Star Trek" as both a blessing and a curse. It certainly made him a celebrity, but it was a level of celebrity he never sought. Stewart wisely differentiated being an "actor" from being a "star," and he clearly preferred the former. He longed to refine his craft and challenge himself, and being a celebrity was antithetical to that. Stewart had been assimilated into the fame machine.

The emotional pain

Stewart wrote about it thus:

"It was an aptly intense storytelling journey for me, too. Locutus knew that Jean-Luc was alive inside him but helpless and trapped, which really resonated with me — the "celebrity" I had become knew that the normal jobbing actor I'd been for most of my life was still there and was the "real" me. Doing those two episodes was emotionally close to home and at times quite painful."

Some actors have a tumultuous relationship with fame. Stewart clearly felt that working on stage, exploring classical roles, and plying his craft in front of a live audience was where his heart truly lived. Being a mass media star certainly brought him a lot of attention, but it also pigeonholed him. To many, Stewart had become Jean-Luc Picard, and he seemingly resented that a little. A presumed audience impulse to see a Patrick Stewart play because he is an excellent actor was replaced by an equally presumed impulse to see a Patrick Stewart play because he's Patrick Stewart.

Surely the attention was flattering, but the above passage reveals Stewart's deep ambivalence. He was assimilated. The "real" him was silenced, deep within a mechanical version of himself that threatened to conquer.

Perhaps that's why Stewart was fine revisiting Borg stories several times in the ensuing decades. Not only were the Borg a fan-favorite villain, but they came to represent the dark side of fame. For a man raised on the stage, they were villains twice over.