Does William Wyler Deserve To Be The Most Nominated Director In Oscars History? An Investigation

(Welcome to Did They Get It Right?, a series where we look at Oscars categories from yesteryear and examine whether the Academy's winners stand the test of time.)

If you were to guess who the most nominated director was in the history of the Academy Awards, who would you guess? Maybe you'd say Steven Spielberg, who has made films for a half-century that have been beloved by millions. Or maybe you're inclination was to guess Martin Scorsese, given his level of simultaneous mainstream acclaim and critical adoration. Or maybe you'd go back to the golden age of Hollywood and guess someone like Frank Capra or John Ford, filmmakers fundamental to establishing what popular American cinema was and directed many films still revered today. In reality, it's not any of these people.

It may come as a surprise to learn that the most nominated director of all time is William Wyler. Over the course of 30 years, Wyler was nominated for Best Director a stunning 12 times — winning three times — and is currently the only one to have a double-digit number of nominations. While his is a name you might know, Wyler isn't exactly a revered household name, especially as auteurism has only grown ever more prevalent as to what makes for a great film. Wyler made grand-scale epics, romantic comedies, costume dramas, crime stories, character studies, and Westerns. William Wyler was the ultimate journeyman filmmaker. Very little linked together his work outside of two things. First, few have ever been able to harness the power of a movie star better than him. Second, the consistency of the quality of his films has rarely been matched. Let's dig through Wyler's dozen Best Director nominations and see if his out-in-front status is justified. Maybe he even deserved more nominations.

Dodsworth

William Wyler was ... a nepo baby. Yes, even over 100 years ago, Hollywood was no stranger to nepotism. Wyler's cousin happened to be the founder of Universal Pictures, Carl Laemmle. To Laemmle's credit, he didn't immediately put Wyler in the director's chair. He spent years doing grunt work before moving up the ladder to being a director in the mid-1920s, making Western programmers. It wasn't until the sound era until Wyler started branching out into different genres, and it would take until the 9th Academy Awards for him to earn his first Best Director nomination for "Dodsworth."

Out of all the films Wyler was nominated for, "Dodsworth" is one of the least remembered, but that says more about the impacts of the other films than the quality of this one. After all, this was not some rogue nomination for Wyler. "Dodsworth" tied for the most nominations of the ceremony, also earning nods for Best Picture, Best Actor (Walter Huston), and Best Screenplay.

Though a fairly stately drama adapted from a play by Sidney Howard, which also starred Huston on Broadway, this would still be a somewhat unusual film if made today. This is a relationship drama about a middle-aged married couple trying to figure out what they want in the second halves of their lives, whether that means together or apart. Movies about proper adults with proper adult issues are such a rarity, and "Dodsworth" handles them beautifully.

Wyler lost the award to Frank Capra for "Mr. Deeds Goes to Town." Because I'm not the biggest "Deeds" fan, and he already won two years earlier, I'd give it to someone else, though Wyler wouldn't be my first choice. My winner would be Gregory La Cava for "My Man Godfrey," but Wyler was a more than worthy nominee.

Wuthering Heights

It would take three years before Wyler received another Best Director nomination, but his Academy success didn't stop. In each of those in-between years, he directed a Best Picture nominee. First was the crime film "Dead End," starring Sylvia Sidney, Joel McCrea, Humphrey Bogart, and the Dead End Kids. The next year, he directed "Jezebel," which also earned Bette Davis her second Best Actress Oscar.

Then came the 12th Academy Awards, celebrating the films of 1939, usually considered to be one of the greatest years in Hollywood history. With that stiff competition, Wyler's adaptation of Emily Brontë's "Wuthering Heights" earned eight nominations, including Best Director. In most other years, you could easily see this film sweeping the Oscars with wins for Picture, Director, and Actor, as Laurence Olivier gives one of his greatest performances. It's a stunning film, and cinematographer Gregg Toland rightfully took home the Best Black-and-White Cinematography prize that night, marking the film's sole win.

Unfortunately for Wyler and the entire cast and crew, this was the year of the "Gone with the Wind" buzzsaw. On the whole, I think "Wuthering Heights" is the superior film, but the staggering scale and success of the Best Picture winner meant it was never going to lose. You have stone-cold classics like "Mr. Smith Goes to Washington," "Ninotchka," "Stagecoach," and "The Wizard of Oz" in the competition, and none of them stood a chance. In that bunch, a film as great as "Wuthering Heights" could still conceivably be in fifth place. Frank Capra beat Wyler last time, but I would be much happier if that happened this year, as "Mr. Smith Goes to Washington" is the far superior film to "Mr. Deeds Goes to Town." Instead, it went to Victor Fleming, which is somewhat difficult to dispute.

The Letter

William Wyler wouldn't wait long to earn his third Best Director nomination, as it would occur the very next year. That means that Wyler directed a Best Picture nominee five years in a row, which — spoiler alert — is a streak that is going to continue. Two years after the success of "Jezebel," he reteamed with Bette Davis once again for the picture "The Letter." Now, I am not the biggest fan of "Jezebel," though I can't deny Davis' performance. For all the things we contemporarily ding "Gone with the Wind" for, "Jezebel" is just as guilty, and it doesn't have the scale and Technicolor splendor of the Best Picture winner either.

Meanwhile, "The Letter" is a major uptick. It still has its highly questionable racial politics, as it takes place in Singapore and features Gale Sondergaard in yellowface, but as a complete whole, it's a far more gripping affair. Davis plays a woman who murders her lover and is all but sure to get away with it, claiming an attempted assault, but a letter is discovered exposing the affair and proves the killing was calculated, which she is blackmailed for by the lover's widow. Davis has played plenty of unsavory characters in her career, and this is easily one of the most unsympathetic, making for a fascinating protagonist in the Hays Code era.

"The Letter" was nominated for seven Oscars but won none. Best Picture went to Alfred Hitchcock's "Rebecca" and Best Director to John Ford for "The Grapes of Wrath," the second of his four wins. While I could easily dispute the previous two winners, I can't with Ford's work on "The Grapes of Wrath." My preference would be George Cukor for "The Philadelphia Story," but Ford is aces and Wyler a deserving bridesmaid.

The Little Foxes

Wyler and Davis bumped heads during the making of "The Letter," particularly about how to play the film's ending, but the relationship wasn't totally severed, as the very next year he insisted that Davis star in his screen adaptation of Lillian Hellman's play "The Little Foxes." That contentious relationship would explode during the making of this film, however. At one point, Davis even walked off the set and refused to return until word of a replacement was being considered. Obviously, this would be their final film together.

In terms of Oscar nominations, what a way to go out. "Jezebel" earned five and "The Letter" seven. "The Little Foxes" earned nine, tying with a little film you might have heard of called "Citizen Kane" for the third most of the evening. Like their previous collaboration the previous year, "The Little Foxes" went home empty-handed, which set a record at the time for the film with the most nominations that didn't win anything.

Also like the previous year, William Wyler lost Best Director to John Ford again, this time for "How Green Was My Valley." That film has become something of a punching bag for film lovers because it sports a flowery title and beat "Citizen Kane" for Best Picture, and I can only assume that anyone who has rolled their eyes at this has never seen "How Green Was My Valley," a truly outstanding picture. Is "Citizen Kane" better? Yes, but the winner wasn't a scrub.

This means that for six years in a row William Wyler directed a highly acclaimed film nominated for a bunch of awards and never got a trophy of his own. Well, that was all about to change. And, you guessed it, it would be the very next year.

Mrs. Miniver

In 1942, Hollywood was not really making movies about World War II. The United States wouldn't enter the war until the end of 1941, and prior to that, they remained frustratingly neutral (and therefore somewhat complicit) in the atrocities taking place. You had "The Great Dictator," but Charlie Chaplin basically operated independently and made whatever he wanted. Outside of that, the subject of World War II was suspiciously absent from cinema screens. But in 1942, it arrived in a big way with William Wyler's new film, "Mrs. Miniver."

Unlike what we usually think World War II films to be, "Mrs. Miniver" is a domestic drama that takes place during World War II about a rural, middle-class family in England as the country enters the war. By centering the film on this family — primarily the titular character played by Greer Garson — it showed the country (and the Academy) about the day-to-day struggles of wartime life and how people can persevere through the horror. It was galvanizing and became the highest-grossing film of the year, setting the stage for "Casablanca" the following year.

"Mrs. Miniver" was the nomination leader at the Oscars with 12 (which included five for acting), and it took home six, including Best Picture, Best Actress for Garson, Best Supporting Actress for Teresa Wright, and, finally, William Wyler for Best Director. After seven straight years of Best Picture nominations, he finally won the gold. Ironically enough, Wyler wasn't present to accept his award. His wife Margaret accepted on his behalf and said, "He's wanted an Oscar for a long time." Out of the Best Director nominees, Wyler stands head and shoulders above the competition, even if something like Michael Curtiz's work on "Yankee Doodle Dandy" is quite good. Nobody else was going to win this.

The Best Years of Our Lives

Wyler was born in Germany and was Jewish, so he had a great deal personally at stake in World War II. After "Mrs. Miniver," he joined the air force and made a couple of documentary series about the war. During his time overseas, he lost hearing in one ear, and in one aerial bombing attack, his cinematographer Harold J. Tannenbaum's plane was shot down, killing the man.

Coming back to the United States after the war, he naturally decided to make a film about coming back from the war, resulting in one of the greatest films ever made. "The Best Years of Our Lives" chronicles three soldiers returning to a small town after World War II to resume their normal lives. Played by Fredric March, Dana Andrews, and Harold Russell, the men deal with the emotional, psychological, and physical scars the war inflicted on them. Notably, Russell served during World War II and lost both of his hands in an explosion. Not only does his presence add a level of authenticity you cannot recreate, but he delivers a soulful, mesmerizing performance despite not being an actor.

The film was released just a year after the war's ending, and like "Mrs. Miniver" before it, it was the highest-grossing film of the year and dominated the Oscars, winning seven of the eight categories it was nominated in, including Wyler's second Best Director Oscar. Its actual win total was eight, as Russell received an honorary Oscar for his work. He also won Best Supporting Actor, so he won two Oscars for one performance.

Even with "It's a Wonderful Life" in competition, the Oscars have rarely gotten the top prizes more right than they did here. "The Best Years of Our Lives" is a monumental American film.

The Heiress

After two decades of cranking out work and going to war, William Wyler took a break after "The Best Years of Our Lives." The world wouldn't see a new Wyler feature for three years when he returned with "The Heiress." Throughout his career, he only took a hiatus between movies that lasted more than two years three times, and one was because of World War II. Wyler worked so much that he would direct another Best Picture nominee after the Academy gave him a lifetime achievement award. So, he may have taken these three years off, but that doesn't mean he lost a step in the slightest.

Adapted from the play by Augustus and Ruth Goetz based on Henry James' "Washington Square," "The Heiress" stars Olivia de Havilland as the titular naïve heiress who falls in love with a poor, handsome man (Montgomery Clift). However, she lives under the iron thumb of her rich father who sees her suitor as nothing more than someone after her money. Stage-to-screen adaptations can often be airless experiences, but "The Heiress" finds the cinematic core of the piece without "opening it up" in the slightest. It recognizes that its intimacy is its strength, and the result is a stunning drama that rightfully earned de Havilland her second Best Actress Oscar.

The winner for Best Director was somewhat surprising, going to Joseph L. Mankiewicz for "A Letter to Three Wives." Mankiewicz hadn't won any precursor awards, but that doesn't mean he snatched it out of Wyler's hands. The expectation was that Robert Rossen was going to win, considering "All the King's Men" won Best Picture while he took home Best Director from the Golden Globes and DGA. Wyler had two already and didn't need three in a row, even if he was worthy of it.

Detective Story

Every year he was eligible for Best Picture, William Wyler directed a nominee for 10 straight years. That is a staggering amount of success. Unfortunately, that Best Picture streak ends here, but that doesn't mean his current streak of Best Director nominations was about to end, because "Detective Story" makes it seven in a row.

This is another stage-to-screen adaptation, but the approach to how to translate it to the screen couldn't be more different from "The Heiress." "Detective Story," which is adapted from the play by Sidney Kingsley, is very much indebted to its theatrical roots, as nearly the entire movie takes place within this one set of a police precinct for the entire film, as the story unfolds over the course of one day. Kirk Douglas stars as a violent cop wanting to uphold the letter of the law at any cost, and in most Hollywood pictures, that guy would be a hero. Not here. His rage and ultra-conservative approach to law and order is seen for what it really is: destructive. But the true stars here are the ensemble populating the precinct, which includes Best Actress nominee Eleanor Parker and Best Supporting Actress nominee Lee Grant (who also won Best Actress at Cannes).

Due to the lack of a Best Picture nomination, it was never expected for Wyler to win Best Director, which went to a more-than-deserving George Stevens for "A Place in the Sun." I'd actually put Wyler in fifth place against the likes of Elia Kazan for "A Streetcar Named Desire," Vincente Minnelli for "An American in Paris," and John Huston for "The African Queen." That isn't to put "Detective Story" down, which is a pretty terrific picture. Wyler's just up against a couple of five-star bangers this year and comes up short.

Roman Holiday

The year after "Detective Story," Wyler directed the turn of the 20th century romance "Carrie," starring Jennifer Jones and Laurence Oliver, reteaming him with his "Wuthering Heights" director for the first time. For the first time in well over a decade for Wyler, no one cared. Critics didn't go for it, and audiences didn't go see it. At the Oscars, it just earned perfunctory nominations for its costumes and art direction, as expected from a period film.

That disappointment was short lived, because he came roaring back with one of his very best films the next year. After working in pretty serious dramas for a while, he gave us one of the most effervescent and delightful romantic comedies of all time in "Roman Holiday," telling the story of the connection between an American journalist (Gregory Peck) and a princess incognito as a civilian (Audrey Hepburn) over the course of a day in Rome. 70 years after its release, this film still plays like gangbusters. It shot Audrey Hepburn into the stratosphere of stardom (and won her Best Actress), and from the second she appears on screen, you completely understand why.

"Roman Holiday" was the second most nominated film of the year with 10, but it was up against a juggernaut in "From Here to Eternity," which won eight of its 13 nominations. That included Fred Zinnemann taking home Best Director. Light-hearted comedies rarely perform well at the Oscars (though they fared somewhat better back then), so it taking home three awards — including Best Story for the then-blacklisted Dalton Trumbo under a pseudonym — is a win. Had it been my choice, though, Wyler would've taken home his third Best Director trophy here. As a consolation prize, he made two more wonderful movies with Hepburn several years later.

Friendly Persuasion

You may have noticed all of these nominated films by William Wyler are in black-and-white. For his narrative fiction features, Wyler worked exclusively in black-and-white until "Friendly Persuasion" in 1956. This saw the director returning to a wartime setting, but here, that meant the Civil War. Like his previous war pictures, though, "Friendly Persuasion" is far less concerned with the theater of battle than it is with how it affects those still living their normal lives. In this case, that is a family of Quakers in Indiana, whose religion and way of life tells them to avoid violence of any kind.

The script for "Friendly Persuasion" written by Michael Wilson played a key part in his blacklisting by the House Un-American Activities Committee, as the pacifist ideology of the story was not appreciated coming out of World War II. The script went through a number of changes by different writers after Wilson's work that removed the fervency of the pacifism, though fragments of that core remain. As the other writers were denied credit by the WGA, the film features no writing credit due to Wilson's blacklisting, and even though he got nominated for screenplay, his nomination was disqualified.

This year at the Oscars exemplifies the height of Hollywood's adulation of bloated spectacles, with "Around the World in 80 Days" notoriously winning Best Picture. For the second time, William Wyler is beaten for Best Director by George Stevens for "Giant," and like his win for "A Place in the Sun," it's perfectly deserved. "Giant" captures what can make those grand-scale Hollywood epics effective, and its nearly three and half hour runtime is utterly captivating from start to finish. Wyler had to settle for a little award called the Palme d'Or, the only one in his career. A fair trade.

Ben-Hur

Speaking of the large-scale Hollywood spectacles of the 1950s, we arrive at what would be William Wyler's penultimate nomination for Best Director, as well as his third and final win. Wyler spent most of the 1950s avoiding what had become Hollywood's favorite genre, the sword and sandals epic. With "Quo Vadis," "The Robe," "The Ten Commandments," and others, this had been the industry's new blockbuster entertainment, pitching them as the big screen pictures you just couldn't get at home on this newly popular device called a television.

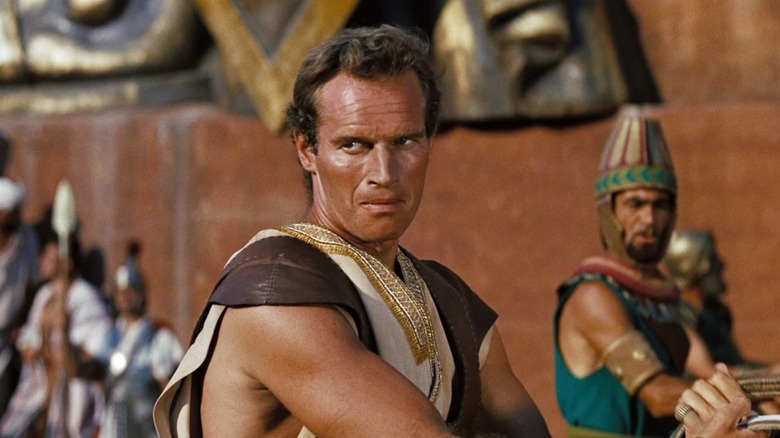

So, when William Wyler stepped in to make his version, he naturally made the one we now all collectively point to when we think of that time in Hollywood with the smash hit "Ben-Hur." This period Roman epic starring Charlton Heston takes all the scope and spectacle audiences had come to know from these kinds of movies and cranks them up to 11, creating one of those movies that still feels like it could be the most expensive film ever made. The chariot race climax, in particular, is one of the most stunning feats ever committed to celluloid. I actually don't think "Ben-Hur" is a great movie, but the wrangling of the production is still awe-inspiring.

At the Oscars, "Ben-Hur" set the record for the most wins in history with 11, later to be tied by "Titanic" and "The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King." Its only loss came in Best Adapted Screenplay. "Ben-Hur" was also the highest-grossing film of 1959. That means every time William Wyler dominated at the Oscars he also had the most financially successful film of the year. After this, though, Wyler wasn't as interested in returning to these massive spectacles, which the Academy would cling onto as we moved into the 1960s.

The Collector

Obviously, the 1960s were a decade of major upheaval in Hollywood. It began with them on top of the world, pumping out lavish spectacles that the audience quickly started losing interest in by the middle of the decade. This led to the radical reinvention of the business and the stripping away of the Hays Production Code, creating the auteur-driven New Hollywood. William Wyler wasn't making movies that fit the Hollywood mold in the first half of the decade anyway, but by the decade's end, his era had been passed by.

His sole Best Director nomination from the 1960s came from a rather unexpected place, both for Wyler and the Oscars. Wyler had tackled a lot of genres up to this point, but he hadn't really made a horror film. Well, in 1965, he rectified that with "The Collector," a story about a man who abducts a young woman to hold her captive in his English farmhouse. This is about as New Hollywood in approach as the director ever gets in style, with him working with two up-and-coming stars in Terence Stamp and Samantha Eggar, both of whom won acting prizes at Cannes for their work.

This was one of those occasions where Wyler was nominated for Best Director but the film wasn't for Best Picture. Eggar did snag a Best Actress nod (and won the Golden Globe), as did the screenplay. "The Sound of Music" and "Doctor Zhivago" were the dominating forces this year, winning five Oscars apiece. Wyler actually turned down directing the former in favor of "The Collector." A small British film like this — especially in a genre the Academy doesn't normally go for — didn't stand a chance against those behemoths. At least the directors' branch recognized an old master continuing to push himself.

What Wyler wasn't nominated for

William Wyler's 12 Best Director nominations makes it seem like they just automatically nominated him every time he made a movie, but that was obviously not the case. Earlier in this piece, I already mentioned that "Dead End" and "Jezebel" each received Best Picture nominations, but that didn't transfer over to Wyler in Best Director. Those weren't the only times his films garnered Oscars attention.

Most notably, you have "Funny Girl." Not only was the film nominated for Best Picture, but it catapulted Barbra Streisand into the upper echelon of movie stardom and won her the Best Actress trophy (in a rare tie with Katharine Hepburn for "The Lion in Winter"). If you're counting, that means five different women won Best Actress Oscars under the direction of William Wyler. The film itself received eight nominations total — the second most of the night — but Wyler just couldn't make it. I've already written extensively about this year's Oscars, as it signified a major push and pull within the industry, so his absence in the lineup is somewhat explainable. He wouldn't be in mine either.

Two other films he made received a lot of Academy love that didn't manifest in nominations for Wyler. 1958's "The Big Country," a terrific Western starring Gregory Peck about honor and the senselessness of violence and guns, may have won Burl Ives Best Supporting Actor, but that was about as much love they gave it. 1961's "The Children's Hour" earned a healthy five nominations, but considering that film's explicitly queer subject matter, that was always going to be a tough sell with the Academy, even if it's a terrific picture. Outside of those, I love "How to Steal a Million," but I know the Academy rarely awards that kind of featherlight comedy.

How many Oscar nominations should Wyler have?

For someone with a dozen Best Director nominations to their name, you might expect that there would be at least one or two among the list that feel perfunctory, like the Academy was just throwing a bone to one of their favorites. When it comes to the filmography of William Wyler, I simply don't think that's the case. I look over these 12 nominations for the director and can easily justify every single one of them. In fact, I would even add one more for his work on "The Big Country," and I could honestly make a case for swapping him out for any one of the nominees that year, including winner Vincente Minnelli for the rather dull movie musical "Gigi." When it comes to wins, he is currently tied with Frank Capra for the second most wins of all time. I believe he should have also won Best Director for "Roman Holiday," which would tie him with John Ford for the most all time.

William Wyler is one of the most versatile, thoughtful, and consistent filmmakers of Hollywood's golden age. It is no accident that he maintained a career of immensely successful movies for decades. This was a filmmaker whose understanding of story and character was rather unparalleled, and although his visual style wasn't showy, he always knew exactly the right frame to convey what he needed, often shooting dozens of takes to get it exactly right. It didn't matter if he made a period epic or a romantic comedy. He could master any genre, minted the biggest movie stars, and crafted some of the greatest films of all time. William Wyler more than deserves to be the most nominated director in the history of the Academy Awards.