Fullmetal Alchemist Has A Big Difference From Other Shonen Anime

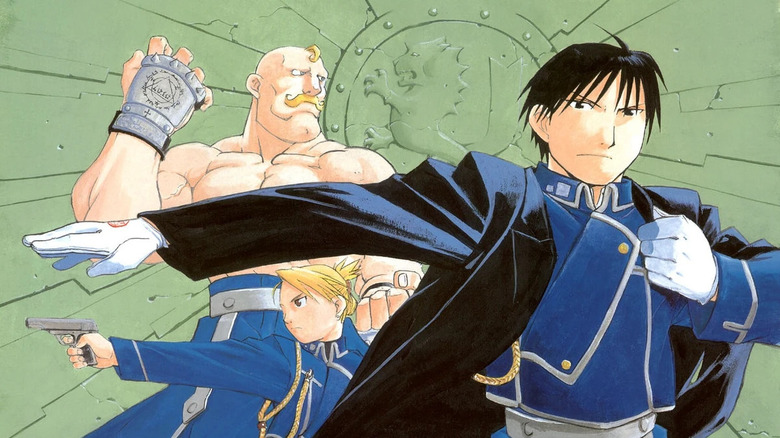

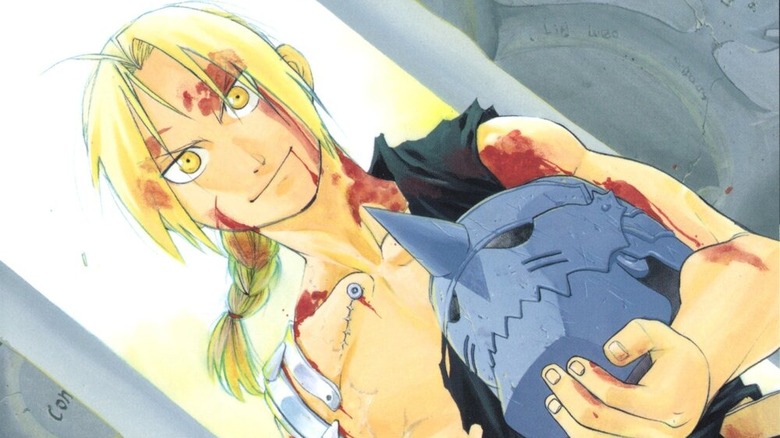

Even if you're only passingly familiar with manga and anime, I'd bet that you've heard of "Fullmetal Alchemist," a modern classic of both mediums. First authored by Hiromu Arakawa and adapted to animation twice, all versions follow the titular alchemist, Edward Elric, and his little brother Alphonse (little in age, not height). Mutilated when they tried to revive their dead mother, they're now on a quest to get their bodies back by finding the Philosopher's Stone. Along the way, they face obstacles ranging from a military dictatorship to ouroboros-tattooed homunculi.

"Fullmetal Alchemist" is not my all-time favorite manga or anime (those titles go to "Monster" and "Neon Genesis Evangelion," respectively), but it is my favorite Shōnen series. What is that? A Japanese term referring to boys' media. Think "Dragon Ball," "Naruto," or "One Piece." They all fit under this umbrella.

Many of these series are published by the same magazine, Shueisha's Weekly Shōnen Jump, but not "Fullmetal Alchemist." If you've ever wondered why the Elric Brothers are nowhere to be seen in the crossover fighting game "Jump Force," or why can't you read the "Fullmetal Alchemist" manga on the Shōnen Jump app, now you know. Some have even mistaken "Fullmetal Alchemist" for a Seinen (adult men) series due to it not being a Jump series and its comparatively darker nature. No, it was published in a Shōnen magazine, just not Jump. And the impact on the story goes deeper than just its manner of distribution.

Fullmetal Manga

"Fullmetal Alchemist" was serialized in Monthly Shōnen Gangan from 2001 to 2010, running concurrently with Jump's "Big Three" series: "One Piece" (began in 1997), "Naruto" (1999-2014), and "Bleach" (2001-2016). It thus enjoyed a height of popularity during the same period as them, which only added to the confusion. However, Gangan is an imprint of Square Enix, home to other manga series such as "Soul Eater" and "Black Butler" (run in Gangan's sister magazine Monthly GFantasy). "Fullmetal Alchemist" is Square Enix's greatest manga success, reportedly having sold over 80 million copies.

Let's run down how manga is published, since it's similar yet different to American comics. In the U.S. comics have traditionally been published in single-issue "floppy" magazines, about two to three dozen pages each (with some of those pages reserved for ads). When superhero comics took hold, characters would headline their own magazines; Marvel would put out separate floppy issues of "Spider-Man," "Fantastic Four," "X-Men" etc.

In contrast, manga chapters run in magazines numbering hundreds of pages, each issue containing all the series in the publication's catalog, printed on cheap pulp pages. Even if a reader only likes a few series, they have to buy the whole magazine issue to read them. Manga chapters for a particular series are then compiled into "Tankōbons," collecting a handful of chapters in a single book. American comics have gradually adopted a similar model with collected editions/trade paperbacks. You even get writers such as Brian Michael Bendis who "write for the trade" (i.e. plot out six-issue long stories, knowing they'll be collected in the same binding soon).

Most American comics run on monthly publication schedules; true to its name, so does Monthly Shōnen Gangan. Jump, however, runs every week, which is evident in how its series are written.

There's no such thing as a painless lesson

Being a manga author (mangaka) is infamous for its punishing work schedule. Mangakas generally write and draw their comics, unlike in America where those duties are split between a writer-artist team. While they don't have to worry about full coloring (manga is traditionally black and white), the workload is still unenviable. Jump in particular has a "survival of the fittest" policy — a series can be canceled after only a dozen chapters if it's not an instant hit.

Masashi Kishimoto, author of "Naruto," reportedly maintained 19-hour workdays for six days a week during his comic's serialization (with only Sundays off). It's no surprise that this overwork can be detrimental to artists and their work. Kishimoto's plea when "Naruto" finished its 15-year-run? "Please let me rest now."

It's also clear that this is why Jump manga series typically have 15-20 page chapters; with the weekly schedule they're on, asking the mangakas for more would be murder. It doesn't always make for the best storytelling though. Chapters often blur together (a single fight scene can be spread over half a dozen chapters), with the narrative taking left turns or running in circles. The plot mechanics of Shōnen manga can sometimes feel like kids on a playground coming up with new rules on the fly. With how little time the authors have to write, it's an understandable problem.

Even so, this is why I'm grateful that "Fullmetal Alchemist" wasn't published in Jump, or on a weekly schedule at all.

The benefits of a monthly schedule

"Fullmetal Alchemist" has 108 chapters, published in 27 volumes (or 18 if you go off the new hardcovers). Compare this with "Naruto" and "Bleach," which have 70+ volumes each, or "One Piece" which is still ongoing with 1000+ chapters. Arakawa got to tell her story on its terms, pacing it to perfection and ending it without it being drawn out or milked (despite her affinity for cows).

Though "Fullmetal Alchemist" uses similar tropes to other Shōnen series, the narrative and setting are more cohesive and considered. Character is what drives the story, not just action. Now, there was a trade-off to the monthly publication schedule; the chapters were longer (usually around 50 pages each), so Arakawa's workload wasn't completely balanced. However, I'd argue that longer chapters are still to the story's benefit.

50-page chapters have more distinct identities than short 20-page ones because, obviously, more happens in them. In turn, that creates more propulsive storytelling momentum. "Fullmetal Alchemist" even asks its audience weighty questions (the biggest one: what's the value of a human life?) because it actually has time to dwell on those ideas. Presumably, Arakawa did too while writing the chapters month-to-month. The series could even tell memorable short stories in a single chapter; see chapter 5, "The Alchemist's Suffering," and the sad fate of Nina Tucker.

These strengths are why "Fullmetal Alchemist" has translated so well into an anime not once but twice. While "Naruto" and "Bleach" inherit pacing problems from their source material, "Fullmetal Alchemist: Brotherhood" is all killer, no filler.

20 years on, the Jump "Big Three" are undoubtedly still popular in all their sprawling glory. "Fullmetal Alchemist," though, proves that a concise package isn't a weak one, and sometimes, the best stories come to those with patience.