Disney Animation At 100: Looking Back On A Century Of Magic

October 16, 2023 marks the official 100th anniversary of The Walt Disney Company. While many enterprises now make up the conglomerate — from theme parks to sports broadcasting — animation has been at its core since the beginning.

The legacy of Walt Disney Animation Studios continues strongly today. 2023 also sees the theatrical debut of "Wish" — the studio's first original fairytale — from the co-director of "Frozen" and starring Ariana DeBose as Asha, the story's protagonist. "Wish" is accompanied in theaters by a new short film, "Once Upon a Studio," starring Mickey Mouse and featuring characters from every feature-length film in the Disney Animation canon.

Even for a studio with such a rich, beloved filmography as Disney's, the past 100 years have been an ebb and flow of highs and lows, hits and bombs, artistic phenomena and creative scarcity. With each generation, Disney Animation must redefine itself for its audience while retaining the signatures that make it iconic. Sometimes it works. Other times it doesn't.

How does each era in Disney Animation's storied history reflect the state of the Disney corporation, and sometimes even provide socioeconomic commentary of the globe's current events? Let's take a look back at a century of magic, marked by the major transitions — for better and for worse — that collectively tell the studio's riveting biography (or at least, the condensed, incomplete, SparkNotes-style version). This is Walt Disney Animation Studios at 100.

1923: Alice's Wonderland marks the beginning of The Disney Brothers Cartoon Studio

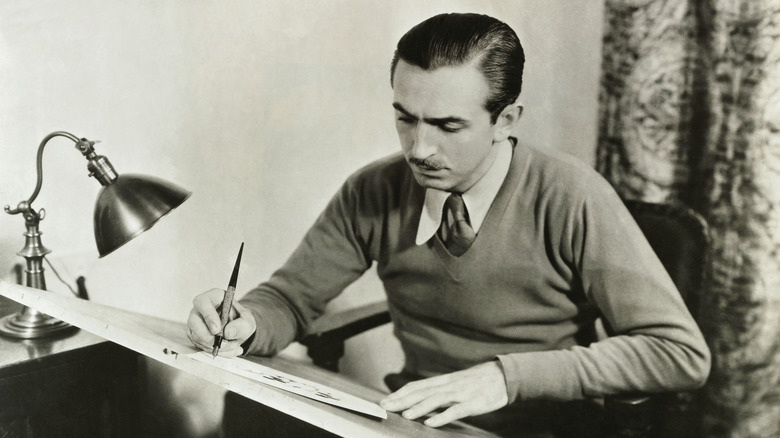

On October 16, 1923, distributor Margaret Winkler signed a contract to commission Walt Disney for a series of short films, which came to be known as the "Alice Comedies," featuring a live-action girl's adventures in an animated world. The signing of this contract is considered the birth of The Walt Disney Company, then known as The Disney Brothers Cartoon Studio, named after Walt and his brother, Roy O. Disney.

Prior to that, though, Walt had developed a sort of pilot episode, "Alice's Wonderland," which convinced Winkler of the series' potential. Even before that, Walt had polished his storytelling and artistic skills in Kansas City with his failed Laugh-o-Gram Films. The first project officially created after the formation of The Disney Brothers Cartoon Studio was "Alice's Day at Sea," released March 1, 1924. In the following years, Disney produced 55 more "Alice Comedies," with animator Ub Iwerks among the studio's talented staff. In 1926, Roy initiated renaming their venture as The Walt Disney Studio.

Beginning in 1927, the studio forayed into all-animated short films starring a new character: Oswald the Lucky Rabbit. The endeavor was short-lived. Oswald cartoons were distributed by Universal by way of Charles Mintz, Winkler's husband. In an infamous blindside, Mintz swindled away most of Walt's animators and continued producing Oswald shorts without Walt, which Mintz was legally allowed to do. One animator who didn't jump ship? Iwerks, whose loyalty to Walt would continue to change filmmaking history.

1928: Steamboat Willie is conjured by a suitcase and a dream

Walt, down on his luck after the fall-out with Oswald, journeyed back home on a train to Hollywood from New York. Aboard the locomotive, legend has it, he drew a sketch of the character who became the world's most famous fictional figure: Mickey Mouse.

So the story goes, shared by Walt in a 1948 essay and often regaled as folklore in the studio's self-told history. For instance, Walt's 1923 arrival in Hollywood is the backstory for the entrance plaza at Disney California Adventure. The area's chipper theme song, "Suitcase and a Dream," integrates Walt's 1928 train ride into its lyrics: "Along the way, he met Mickey Mouse, and the world will never be the same."

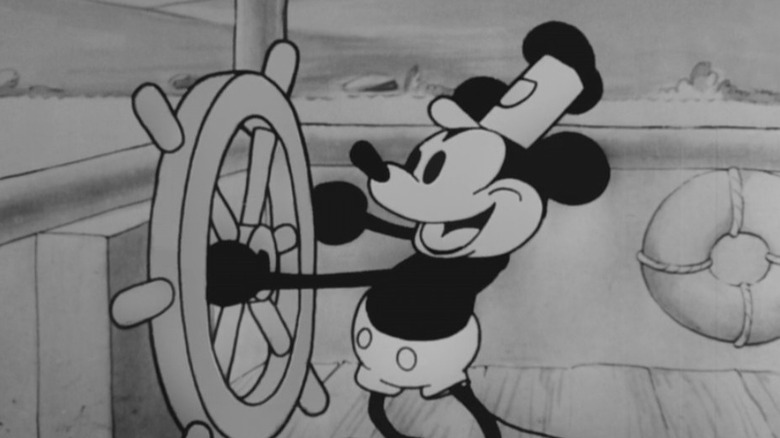

Deflated but not defeated following the major upheaval of his artists, Walt, along with Roy and Ub, embarked on reclaiming a stake in the animation industry, beginning with "Steamboat Willie," the world's first cartoon with synchronized sound and the first publicly released appearance of Mickey Mouse. ("Plane Crazy" and "The Gallopin' Gaucho" were created first, but released later.)

In 1929, The Walt Disney Studio became Walt Disney Productions, a name it would keep for over 50 years. Disney laid the foundation for his studio's future with an arsenal of black-and-white Mickey shorts and "Silly Symphony" cartoons, a series of shorts based upon myths and fairytales. Iwerks championed the animation, becoming an unsung hero who excelled in his craft and surged Disney to new heights.

1932: Flowers and Trees planted Disney's roots

Walt Disney's first project in color earned him his first Oscar. "Flowers and Trees," a 1932 "Silly Symphony" short about romantically infatuated flora, won an Academy Award for best cartoon short subject. The cartoon marked a turning point in more ways than one. Walt had a new tool, Technicolor, to present his animators' vibrant storytelling. In effect, Hollywood had a new rising star: Walt himself.

Though it's wild to think about now, success wasn't guaranteed for Walt Disney. In 1932, "Disney" wasn't a media titan; it was a person, whose time in Tinsel Town could have been brief if the public didn't connect with his work. Notably, the same year, the Academy gave Walt a special award for "the creation of Mickey Mouse," a testament to the character's imprint on popular culture. Disney and his animators understood the alchemy of character development on a spiritual level and the mechanics of character animation on a practical level. The studio had gone from a startup small business to an established fixture of Hollywood and beyond.

As the '30s progressed, the studio's success continued with more "Silly Symphony" shorts and Mickey Mouse cartoons. In the former category, 1933's "The Three Little Pigs" was a phenomenon we might equate to "Frozen" today. Audiences loved "The Three Little Pigs" so much that theaters sometimes advertised it more prominently than the feature film it accompanied. Meanwhile, Mickey's adventures added new pals Donald Duck, Goofy, and Pluto.

1937: Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs charts new territory

Disney's — and America's — first full-length animated film laid a foundation that everything else would follow. The previous decade that the animators had spent sharpening their skills on short-form "Silly Symphony" musical fairytales paid off. In 1937, "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs" proved Disney and his artists were capable long-form storytellers . They didn't just create cartoons — they crafted cinema. "Snow White" was the highest-grossing movie ever at the time of its release, and again earned Walt a special Oscar for a groundbreaking achievement in filmmaking (well, actually, eight Oscars: one regular-sized statue, and seven smaller ones).

It was immediately clear that "Snow White" wouldn't be a one-off; Disney would henceforth be in the business of feature-length animation, a new frontier. That being said, the studio didn't entirely discontinue short films. New audience favorites Donald, Goofy, and Pluto each headlined their own series, alongside Mickey's further adventures.

Following "Snow White," Disney debuted "Pinocchio" in 1940. The studio's sophomore outing featured "When You Wish Upon a Star," a song that went on to win an Oscar and become an anthem of sorts for Disney as a company. Also in 1940, Disney released "Fantasia," an anthology of sophisticated fantasies set to classical orchestration. Reflecting decades later, Walt called "Fantasia" an "artistic success," but a "financial failure." Neither "Fantasia" nor "Pinocchio" were financially rewarding in their original runs. Today, they're regarded among the studio's best films — examples of superb storytelling, sets, character animation, and special effects.

1941: Dumbo debuts as the U.S. enters World War II

On October 23, 1941, "Dumbo" debuted in theaters. Not long after, on December 7, 1941, the Japanese military attacked Pearl Harbor. Suddenly, the United States had entered World War II. Now infamously, Time Magazine had planned for "Dumbo" to grace the cover of its next issue. Obviously, the war took precedence. (However, "Dumbo" retained a feature story within the magazine, still accessible online today.) In the years that followed, Disney, like many companies, changed its business model and strived to aid the war effort, out of both necessity and patriotism. America's entry into the war didn't derail "Bambi," an artistic triumph, which was already far enough along in production to cross the finish line for its 1942 release.

However, from that point forward, Disney switched gears away from long-form storytelling. Instead, the studio produced "package features": full-length productions comprising several segments. Sometimes these sequences thematically connected; other times the assembly felt completely random. Movies released within this period included "Saludos Amigos," "The Three Caballeros," "Make Mine Music," "Fun and Fancy Free," "Melody Time," and "The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad."

Meanwhile, short films starring Mickey and his friends reflected the realities of the era. Donald Duck got drafted into the U.S. army in a multi-story arc. Minnie Mouse encouraged audiences to donate their leftover bacon grease to be used to make explosives. Even within the escape of a Disney picture, life wasn't a fairytale anymore.

1950: Cinderella redefines what makes a Disney film

Post-war, Disney's comeback project was 1950's "Cinderella." As the first full-length Disney picture in eight years, and as an immaculately animated kaleidoscope of songs, sorcery, and a princess-in-waiting, it's not a stretch to consider "Cinderella" a rebirth of the Disney art form, parallel to "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs" and the advent of the studio's filmography in 1937. Notably, the official Disney encyclopedia, preserved on D23.com, theorizes if "Cinderella" had failed, "it probably would have sounded the death knell for animation at the studio."

Successive features in the 1950s — "Alice in Wonderland," "Peter Pan," "Lady and the Tramp," and "Sleeping Beauty" — showcased a studio at the apex of its aesthetic. Disney, with its panache for breathtaking fairytale vistas and strong-willed heroes, perfected the genre it had pioneered: fantasy-bent literature adaptations.

Within this same decade, we see the beginnings of multi-platform Disney synergy expertise. During the '50s, Disney branched out in three key areas: live-action filmmaking (first with "Treasure Island"), television (with a Walt-hosted weekly family program and the "Mickey Mouse Club" children's variety show), and the conception and opening of Disneyland.

While we're mostly sticking to Disney Animation in this article, rather than Disney at large, these milestones in the '50s influenced the studio's future in animation significantly. As director Sarah Colt points out in Walt-focused 2015 episodes of the PBS docuseries "American Experience," Walt's increased interest beyond animation consequently, gradually, meant a less-personal involvement with animated films coming through the pipeline.

1961: One Hundred and One Dalmatians captivates audiences in an overlooked Disney era

By the 1960s, Walt had recruited many of his veteran animators to join WED Enterprises (today known as Walt Disney Imagineering), the group of artists who designed theme park attractions. With Walt's attention largely vested in attractions for Disneyland, the New York World's Fair, and a Florida project he envisioned for the future — as well as "Mary Poppins," the crown jewel of his live-action filmmaking career — the animation studio kept chugging along.

"One Hundred and One Dalmatians," released in 1961, grossed $14 million, nearly three times the amount of the preceding Disney animated feature ("Sleeping Beauty," which grossed $5 million). In 1963, "The Sword in the Stone" uneventfully followed, its box-office receipts lacking credible sourcing online but nonetheless not as well-remembered in comparison to other Disney films of the era. By this time, the studio had moved on from developing cartoon shorts starring Mickey and friends. In 1966, it introduced its take on A.A. Milne's classic storybook character with "Winnie the Pooh and the Honey Tree," a half-hour featurette and the unassuming beginning of a future major Disney franchise.

At the end of 1966, the animation studio and all of Walt Disney Productions lost its guardian; Walt Disney died of lung cancer at the age of 65. Artists were suddenly faced with the impossible task of creating Disney movies without the guidance of their namesake.

1967: The Jungle Book finds Disney in identity crisis

In 1967, "The Jungle Book" became the first animated feature released after Walt's death, though he had been very involved in its production. When assessing the filmography that followed, we can see a ship struggling to chart a course without its captain. The vessel stays afloat and keeps the journey moving, but it's hardly making the waves it once was. In the wake of Walt Disney's death, the animation studio he left behind produced "The Aristocats," "Robin Hood," "The Rescuers," and "The Fox and the Hound" between 1970 and 1981.

The bright spots in animation during the post-Walt era were the studio's occasional half-hour featurettes. Following the first Pooh project from 1966, Disney produced the Oscar-winning "Winnie the Pooh and the Blustery Day" in 1968 and "Winnie the Pooh and Tigger Too" in 1974. In a unique move within Disney's animated canon, in 1977 the studio stitched the three previously released Pooh stories together into a feature-length production, "The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh." In 1983, Mickey Mouse returned to the big screen with the Oscar-nominated "Mickey's Christmas Carol." The now-perennial holiday tale was paired in theaters with a re-release of "The Rescuers" (a factoid that will be important later).

Elsewhere, Imagineers continued with Walt's Florida project, which came to be known as Walt Disney World by its 1971 opening. Two months after the resort's debut, Roy O. Disney, Walt's brother who had steadfastly held the company afloat since its inception in 1923, died.

1985: The Black Cauldron ushers new Disney leadership

By the mid-1980s, Walt Disney Productions had gone through three CEOs since Roy's death.In 1984, it welcomed a fourth: Michael Eisner. He came aboard alongside president/COO Frank Wells and studio chairman Jeffrey Katzenberg. In alignment with the new regime, in 1986 Walt Disney Productions became The Walt Disney Company. The animation department, which had simply existed under the WDP banner for decades, became Walt Disney Feature Animation and instated new leadership of its own, including Roy E. Disney (Walt's nephew and Roy O. Disney's son).

Bluntly, the new executives saved Disney from self-implosion. Disney's 1985 animated film "The Black Cauldron" was already underway upon their arrival. "The Black Cauldron" was a financial, critical, and narrative failure — a wake-up call that Disney's future in animation wasn't guaranteed.

Katzenberg challenged animators to move forward and buck tradition. This spirit of defying convention and identifying new talent led to a series of films with each improving upon its predecessor. During the production of "The Black Cauldron," Katzenberg insisted that an animated film could be edited, a practice the artists had long resisted due to the intense labor and expense of producing finished sequences.

Under Katzenberg's leadership, 1986's "The Great Mouse Detective" was the first Disney film partially directed by Ron Clements and John Musker; 1988's "Oliver & Company" was the first to include lyrics written by Howard Ashman. All three creatives will be very important in the years to come. In their '80s-era Disney work, we see glimmers of the greatness yet to come.

1989: The Little Mermaid, by way of Howard Ashman, saves Disney

Disney animation soared under the leadership of Katzenberg, Roy E. Disney, their direct reports, and the macro supervision of Eisner and Wells. 1989's "The Little Mermaid" was Disney's first fairytale musical in nearly 30 years, the studio's artists communicating loud and clear they were every bit as capable of continuing the Disney legacy as the masters of Walt's time. Clements and Musker directed "The Little Mermaid," with Ashman serving as executive producer, lyricist, and overall creative genius. Alan Menken provided music.

"The Little Mermaid" initiated a wave of masterpieces, aided by a new satellite campus in Florida. Audiences could hardly catch their breath between instant classics. The studio released "Beauty and the Beast," "Aladdin," and "The Lion King" consecutively across 1991-1994, an incredible streak. Indicative of the respect Disney had earned during this time, "Beauty and the Beast" became the first animated film receive a best picture nomination at the Oscars. Additionally, "Mermaid," "Beauty," "Aladdin," and "Lion King" all won Oscars for best song and best score, thanks to various combinations of Ashman, Menken, Tim Rice, Elton John, and Hans Zimmer writing a treasure trove of remarkable melodies.

The outlier of this period was 1990's "The Rescuers Down Under," Disney's first animated sequel. It underperformed so poorly during its opening weekend that Katzenberg prematurely canceled its remaining TV ads, deeming the film's chances of financial success a lost cause. But even this disappointment stands as an important landmark — "The Rescuers Down Under" was the first film ever entirely assembled digitally, with the Computer Animation Production System (CAPS) allowing artists to color and composite the animators' work in a whole new way.

1995: Pocahontas debuts in the middle of executive tragedy and shake-up

By 1994, Walt Disney Feature Animation was at its zenith of influence, box office revenue, creativity, and accolades. That's when a series of tragedies and transitions prevented its further ascent. Ashman had died during the pre-production of "Aladdin" as a victim of the AIDS epidemic. Wells died in a helicopter accident just before "The Lion King" debuted. In the wake of these losses, Katzenberg departed Disney in 1994 (and shortly thereafter co-founded DreamWorks Animation). Eisner remained Disney's CEO.

Beginning with "Pocahontas" in 1995, the second half of Disney's 1990s saw more modest successes that seemed to reflect the disarray and overexertion behind the scenes: "The Hunchback of Notre Dame," "Hercules," "Mulan," "Tarzan," and "Fantasia 2000." They're mostly well-regarded today, but didn't shift the needle of pop culture like the films of the early '90s had.

In 1995, Disney distributed "Toy Story," the first movie from a computer graphics company called Pixar. Simultaneously, Walt Disney Television Animation struck gold with "The Return of Jafar," a direct-to-video sequel to "Aladdin" produced for a fraction of the original's cost. Successes in both ventures led to more partnerships with Pixar and an onslaught of additional sequels produced by the TV division.

The films of Pixar and Disney Television Animation (which later expanded its feature efforts as DisneyToon Studios) aren't officially considered part of Disney Feature Animation's canon, but the rise of these brands redefined the company's future in major ways.

2000: Dinosaur takes Disney into the 21st century

In the new millennium, Walt Disney Feature Animation struggled to keep up with the very industry it had pioneered. 2000's "Dinosaur" marked a distinct shift in both form and function for the studio, an indication of a desire — if not desperation — to forego the traditional "Disney" tone and emulate competition. Its characters were computer-animated, not hand-drawn. Its story was an epic drama, not a fairytale musical.

The studio continued to experiment across genres with its early-2000s filmography: "The Emperor's New Groove," "Atlantis: The Lost Empire," "Lilo & Stitch," "Treasure Planet," "Brother Bear," "Home on the Range," and, in 2005, the studio's first completely computer-animated movie, "Chicken Little." Within this chronology, we see an earnestness for something, anything, to stick with audiences' tastes. "Lilo & Stitch" was an outlier — a financial success and a juggernaut of Disney synergy on pace with the big leagues of the '90s.

The ups and downs reflected corporate turmoil within. Roy E. Disney departed the studio in 2003 and led a campaign for Eisner's removal as CEO. The Florida branch — which had created "Mulan" and "Lilo & Stitch," arguably the studio's most well-received and lucrative films in recent memory — closed in 2004. Disney's relationship with Pixar reportedly soured, despite Pixar's continued success. Eisner conceded as Disney CEO in 2005, replaced by Bob Iger. Among Iger's first orders of business? Reclaim Disney's ownership of Oswald the Lucky Rabbit from Universal. Okay, sure. Anything else? Oh, yeah: Purchase Pixar.

2007: Meet the Robinsons displays Pixar's influence

Walt Disney Feature Animation and Pixar Animation Studios remained separate entities following The Walt Disney Company's acquisition of Pixar in 2006. However, as part of the $7.4 billion purchase, key members of Pixar's leadership became Disney Animation's creative leaders too, splitting their time shepherding projects from both studios. These leaders were tasked with salvaging in-progress projects and thereafter charting a course to get Disney back to being "Disney."

Just like with the shake-up of executives in the 1980s, the new leadership signified its presence — and hopefully a new dawn for the studio — with a new name. In 2007, Walt Disney Feature Animation became Walt Disney Animation Studios. The rebrand came complete with a new roll-in logo to appear before every Disney Animation film, featuring Mickey Mouse happily whistling in 1928's "Steamboat Willie."

The prospect of a Disney Animation revival was promising, but success would take time to rebuild. Post-"Chicken Little," the Disney Animation filmography gradually found its center. 2007's "Meet the Robinsons" proudly hailed a Walt Disney quote, "keep moving forward," as its thesis, repeated throughout its story and attributed to Walt in the end credits. 2008's "Bolt," about a dog actor lost in the wild, carried a Pixar-esque combination of a clever story and endearing characters. Though not earth-shattering triumphs, these movies in succession indicated Disney Animation was getting back on track. The studio then approached its true test of worthiness: Could it create a fairytale musical like the days of yore?

2009: The Princess and the Frog revives Disney storytelling

Directed by Ron Clements and John Musker — the same duo who had directed "The Little Mermaid" two decades prior — 2009's "The Princess and the Frog" radiated anticipation in its promotional campaign. It was a fairytale! It had songs! It starred a new princess, Tiana! It was hand-drawn!

While not a huge commercial hit upon release ("Bolt" fared better at the box office), "The Princess and the Frog" initiated a new wave of Disney stories that connected with audiences again. 2010's "Tangled" was a musical with a timeless, European fairytale aesthetic. 2011's "Winnie the Pooh" was a charming, hand-drawn callback to its namesake character's earliest films. 2012's "Wreck-It Ralph" was an exceptional example of creatively dynamic world-building. In short, Disney was back.

If "The Princess and the Frog" poised hand-drawn animation for a long-term comeback, "Winnie the Pooh" snuffed out the possibility. Despite critical praise, the latter bombed financially, perhaps thanks to Disney's bewildering decision to release it on the same day as "Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 2." However, with the 2012 short film "Paperman," the studio presented a proposal for a future in which traditional and computer-generated animation could create something new, together.

"Paperman," in black-and-white, told a love story in an idyllic cityscape, with a transcendent score by Christophe Beck. The Oscar-winning short exuded a visual and narrative confidence that cinephiles today might compare to "Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse" ... six years before that movie slung into theaters.

2013: Frozen cements Disney Animation as seismic storytellers again

The trailer for "Frozen" hailed the film as "the greatest Disney animated event since 'The Lion King.'" That bold prophecy came true. Grand musical production numbers, stunning effects animation, and a delightful cast of characters propelled "Frozen" to don the crown of highest-grossing animated film of all time. In directing "Frozen" with Chris Buck, Jennifer Lee became the first woman to direct a feature film from Disney Animation.

"Frozen" ushered in a wave of films that achieved sensation status worldwide: "Big Hero 6" in 2014, followed by "Zootopia" and "Moana" in 2016. All were critical and commercial titans. One of the most euphoric qualities of this Disney resurgence was a return to musicals. Songwriters Randy Newman ("The Princess and the Frog"), Alan Menken and Glenn Slater ("Tangled"), Kristen Anderson-Lopez and Robert Lopez ("Winnie the Pooh," "Frozen"), and Lin-Manuel Miranda, Mark Mancina, and Opetaia Foaī ("Moana") created melodies that felt at home alongside classic Disney tunes.

Songs extend the longevity of Disney movies, providing entry points for theme park attractions, stage shows, and in some cases even radio to keep the film in public consciousness. After a period of scarcity in the 2000s, Disney Animation was providing its corporate partners — and, more importantly, audiences — with limitless storytelling.

Meanwhile, DisneyToon Studios renamed itself — or rather, re-punctuated itself — to Disneytoon Studios in 2013. No longer creating sequels, Disneytoon focused on two spinoff movie series: Disney Fairies, starring Tinker Bell, and "Planes," derived from Pixar's "Cars."

2017: Olaf's Frozen Adventure signals a franchise-driven flurry

"Olaf's Frozen Adventure," a half-hour Christmas tale, was created by Walt Disney Animation Studios with the intent of being a television special. Instead, it released theatrically with Pixar's "Coco" in 2017. Disney no doubt hoped to repeat the success of 1983's "Mickey's Christmas Carol," which had debuted alongside a feature film and became a holiday favorite. With Olaf, though, audiences were confused and confounded. "Am I in the right theater?" "When will this be over?" Disney either failed to inform audiences what they were walking into, or miscalculated the concentric demographics between "Frozen" and "Coco." Both could be true.

In any case, "Olaf's Frozen Adventure" embodied Disney's zealousness to push franchise-focused projects upon consumers. Disney Animation's next two features were sequels: 2018's "Ralph Breaks the Internet" and 2019's "Frozen 2." Remember, almost every animated Disney sequel prior to these had been created by Disneytoon, not Disney Animation. The eagerness of Disney Animation, the upperclassmen, to jump onto the sequel train was rare and notable. It indicated a major shift in the studio's approach to revisiting its stories. Despite what we might refer to as "the 'Coco' incident," audiences holistically weren't done with Anna and Elsa; "Frozen 2" topped its predecessor's record as history's top-earning animated film.

What transition are we in today?

It's difficult to pinpoint a transition in the present, simply because we're in it. That being said, the onset of the pandemic and/or the back-and-forth Disney CEO shuffle between Bob Iger and Bob Chapek are easy targets for future generations to plot as major turning points for Walt Disney Animation Studios. The modern era is an unsteady flow of megahits ("Encanto"), failures ("Strange World"), pandemic-impacted projects that never got their chance to shine ("Raya and the Last Dragon"), and Disney+ originals ("Baymax!" and "Zootopia+").

Seemingly contradicting Disney Animation's newfound affection for franchises, the company closed Disneytoon Studios — an entity that existed for the sole purpose of franchise development — in 2018. To add to the paradox, in 2022, Disney Animation opened a Canada branch to focus on direct-to-streaming projects. So ... kinda like Disneytoon? (The branch also bears uncanny resemblance to Pixar Canada, a short-lived annex that focused on Pixar franchises.)

Looking ahead, Disney Animation's release calendar — under the forward-thinking, innovative stewardship of Jennifer Lee as the studio's chief creative officer — is a balancing act of surefire hits sprinkled among exciting artistic risks. Following "Wish," Disney Animation will debut sequel films to "Frozen" and "Zootopia," sequel series to "The Princess and the Frog" and "Moana," and an original series, "Iwájú," in partnership with Pan-African media company Kugali. All of these projects remain undated, while the projects with dates remain unnamed. To-be-announced Disney Animation films will debut theatrically Thanksgiving week in 2024, 2025, and 2026.