Indiana Jones And The Last Crusade Made A Small But Key Change In The Franchise's Cinematography

Although "Raiders of the Lost Ark" is probably the most widely beloved of them, a strong argument can be made that "The Last Crusade" is the real best entry in the Indiana Jones franchise. The duplicitous Elsa makes for perhaps the most compelling of Indy's love interests, and the introduction of Sean Connery as Indy's father paves the way for a more introspective look at Indiana as a person. "Temple of Doom" might technically be the only prequel in the series, but it's this third movie that seems most interested in exploring Indy's past.

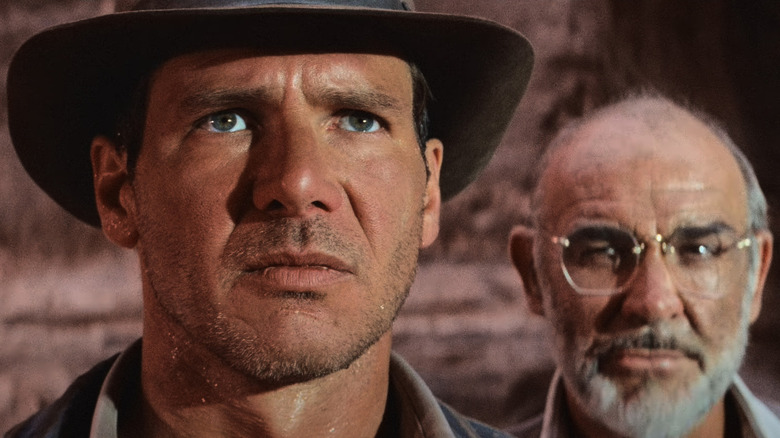

The result is that this is the most intimate of the "Indiana Jones" movies, the one that cares the most about its main character's emotional journey. It's a choice that's reflected in the cinematography, which favors close-ups over the wider shots of the first two films. Some of the most memorable images of "Raiders" are of the diggers' silhouettes working over the desert sunset, or of Indy shooting that guy instead of fighting him the hard way. For "The Last Crusade," those moments that stick with us are of young Indy's face transitioning to adult Indy's, or Indy's reaction as his father tells him to let the grail go, finally calling him Indiana instead of Junior.

As the movie's cinematographer Douglas Slocombe explained in an interview with The American Society of Cinematographers, "One photographic difference between this film and the first two is the increased use of the close-up ... We used the tight shot to momentarily concentrate the action and attention more often than in the past."

A movie that lingers

It makes sense to take this approach, as this is a movie where all the characters are stuck in uncertain emotional places. For instance, Elsa betrays Indy and joins the Nazis, but still gets a character arc where she realizes that allying herself with the Nazis isn't worth it. She purposely suggests the wrong cup to greedy Nazi-sympathizer Walter Donovan at the end; it's a moment that could've easily flown over viewers' heads, considering she's still surprised by the sheer level of violence the cup does to Donovan's body, but the movie makes her intentions clear through a series of close-ups on Elsa and Indy. Elsa is easily the least straightforward of any of the leading women in those first three Indy films, so the subtle shift in approach fits well.

The close-ups make even more sense with all the conversations between Indy and Henry, a relationship loaded with far more history than any other Indy's had in these films. During the early conversation between the two on the blimp, where Indy confronts him on ignoring him his whole childhood, the camera inches closer and closer on the actors' faces as the conversation grows more intense, culminating in a prolonged close-up on Indy as he's asked what he wants to talk about.

It's the heaviest moment in the scene, where Indy's fully hit with the weight of how disconnected he feels from his father, and it works mostly because of how adamantly the camera stays glued to him for his whole reaction. Moments like these were a lot rarer in the first two films, which might be why Slocombe loves the third one so much. "It's a fascinating story," he told the ASC. "I think that the third may be the best of them all."