The Virgin Suicides Ending Explained: Making Myth Of Memory

In a suburban neighborhood in the mid-1970s, all five teenage girls in the Lisbon family die by suicide, forever changing the lives of the boys who lived nearby. Sofia Coppola's 1999 film "The Virgin Suicides" is tragic and isn't always easy to watch, but it's a beautiful and eerie dive into the secret lives of teen girls, the reach of grief, and the malleability of memory. The film was Coppola's directorial debut and she wrote the screenplay as well, based on the 1993 novel by Jeffrey Eugenides.

"The Virgin Suicides" has gone through waves of popularity, as it was beloved on the festival circuit only to barely make back its budget at the box office. Later it found cult status on home video, joining the Criterion Collection in 2018. It's a deeply challenging film because the impending deaths of the girls loom over every scene — in a way, we know the ending before the first frame even plays. Instead of delivering a standard narrative and all of the terrible, graphic details like tawdry true crime, Coppola took a page from the source material and made the narrators unreliable, their depiction of events tainted by their own perspectives.

"The Virgin Suicides" is narrated by the adult versions of the boys who found themselves enchanted by the Lisbon girls, and they tell the story of what happened as best they can. Because the story is told through the framework of memory, it's often dreamlike and can be a bit confusing, especially when it comes to the film's shocking conclusion. Let's look a little deeper at "The Virgin Suicides" to explain what all of the odd moments, metaphors, and that ending all really mean.

What you need to remember about the plot of The Virgin Suicides

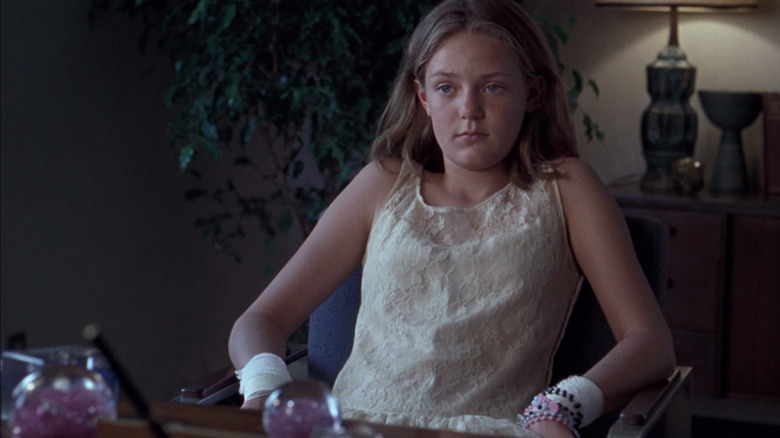

After a suicide attempt by the youngest Lisbon sister, Cecilia (Hanna R. Hall), doctors recommend that the girls be given some kind of social life outside of school. Private school math teacher Ronald Lisbon (James Woods) and his extremely devout Catholic wife Sara (Kathleen Turner) are hesitant to let the girls interact with the world at all and have sheltered them to extremes, but they relent. They throw a party for Cecilia and invite boys and girls from the neighborhood, but Cecilia leaves and dies by suicide. Her death has a profound impact on the family but they try to keep going in the face of their grief.

After Cecilia's death, the neighborhood boys start collecting items that the Lisbon girls once owned, starting with Cecilia's diary. They try to learn everything they can about the mysterious girls, and because they are our narrators we only really see the girls in glimpses, through moments the boys shared with them, guesses they make, or their observations from Cecilia's diary.

The sisters get one big chance to enjoy themselves when high school bad boy Trip (Josh Hartnett) convinces Mr. Lisbon to let Lux (Kirsten Dunst) go to Homecoming as long as he can find dates for the other three girls. After Trip abandons Lux on a football field and she ends up getting home the next morning, however, the Lisbons go into total lockdown. They take the girls out of school and shut out the world in a desperate attempt to protect them.

What happened at the end of The Virgin Suicides?

On top of keeping the girls trapped at home, Mrs. Lisbon also forces Lux to destroy her rock records, which devastates her. Instead of protecting the girls, she forces them into a deeper depression. The boys see Lux having sex with random teens and men on the roof of her house late at night, desperate to act out or find comfort, though we'll never know which.

The sisters then begin to contact the boys through notes and Morse code using their lamp and the boys' telescope, setting up a meeting at midnight where the girls will supposedly need the boys' help to escape. When the time comes, they meet Lux at the back door and are ready to run away, having taken the keys to one of their mothers' cars. However, Lux tells them to come inside and wait for her sisters to finish getting their things, then she'll meet them in her family's much bigger car so they'll have more room. The boys wait and even call for the girls but they don't appear, leading the boys to go looking. What they find is that each of the sisters has died by suicide in some way, escaping their parents' oppressive rules in the most extreme manner possible.

We see the Libson girls in photos on local news channels, their tragedy made into a bit of entertainment for bored housewives. The neighborhood moves on, though the boys can never forget their experiences or the girls. Though the adults clearly don't really care and some even make jokes about teenage suicide, the girls' peers are impacted forever.

To be unknowable and unknown

The movie's main thesis is laid out in its opening sequence, in which Cecilia is told by her doctor that she's too young to know how bad life could possibly be and Cecilia replies, "Obviously, doctor, you've never been a 13-year-old girl." The story is told by everyone but the Lisbon sisters, as even Cecilia's diary entries are impacted by the reader. They are fantasies, ephemeral nymphs dreamed up by the boys based on their brief interactions. We even see the boys daydream about traveling with the girls to far-off lands or escaping to somewhere, anywhere but suburbia. In Eugenides' novel, the girls are completely unknowable, to the extent that he imagined each sister being played by multiple performers to highlight their shifting nature depending on whose perspective we're seeing them through.

Coppola injects the film with the perspective of someone who has actually been a teenage girl, and the audience can get to know the girls through the things that go unsaid. The narration never tells us that the parents begin to fall apart after Cecilia's death, but we see it in the way the house is suddenly untidy, with half-eaten food strewn about and the yard in disarray. Mrs. Lisbon becomes increasingly disheveled, while Mr. Lisbon begins acting so erratically that he's fired from his job — something we only learn because some neighbor women are gossiping about it. Through these moments we get a hint of what it's like to be one of the sisters, to be unknown and unknowable, with only your siblings knowing your true self, if that.

Different kinds of rot

Coppola's handling of the girl's perspective is a sneaky bit of feminist commentary on what it's like to be a woman whose story is told by a man, but what about the rotting tree? There's an elm in the front yard, beloved by Cecilia, that is due to be cut down because it's infected with a kind of fungus that could take out all of the other elms in the neighborhood (and there are a lot of them). When the crews come to cut down the tree, the girls run out in protest, trying to protect this thing their departed sister loved so much. The tree ends up spreading its fungus throughout the neighborhood, effectively killing almost all of the big, proud elms.

This spreading rot represents local fears about suicide, the impact of grief on the Lisbon family, and the infectious obsession within the boys. The way the girls protect the tree and protest when told that it's too late because the tree is "dead" shows their unwillingness to let go of their sister and their own desire to keep going, even if their own fates feel doomed.

If you or someone you know is struggling or in crisis, help is available. Call or text 988 or chat 988lifeline.org.