Free Willy Was Based More On Lies Than A True Story When It Was Released In 1993

The perception of orcas has changed a lot in the past few decades. Though revered by some cultures (such as several Native American tribes and the Ainu of Japan), they've historically shared the bad reputation of sharks — there's a reason the name "killer whale" endured.

Then in the 1960s, scientists began studying these animals up close and perception slowly changed. While orcas are apex predators, they have no documented interest in hunting humans; if anything, they're playful (they're literally big dolphins, after all). They're also some of the smartest animals around, with intelligence comparable to great apes; they communicate with each other and different pods have different languages.

This change in perception can be seen in film. In 1977, "Orca" was a "Jaws" knock-off that depicted a killer whale as a modern Moby Dick. By 1993, an orca became the star of a family movie: "Free Willy." I've not revisited "Free Willy" in over a decade, but it is a childhood favorite. My love for movies began with my early fascination with animals; I was drawn to the VHS from the cover.

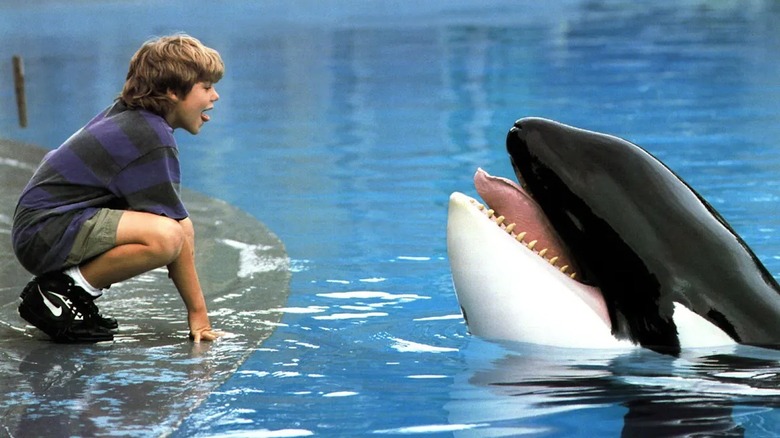

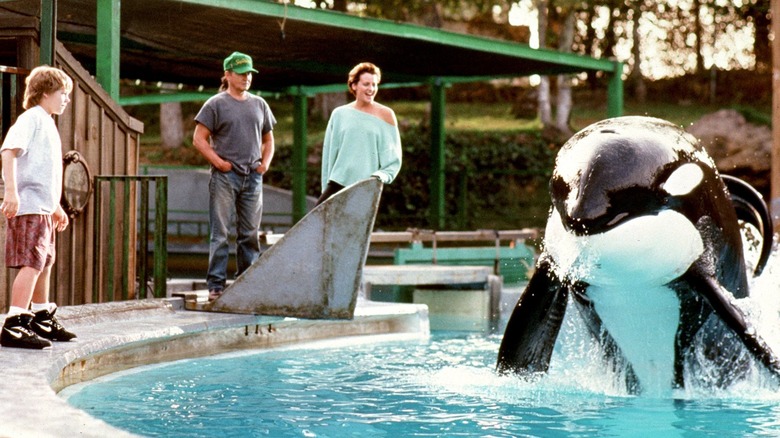

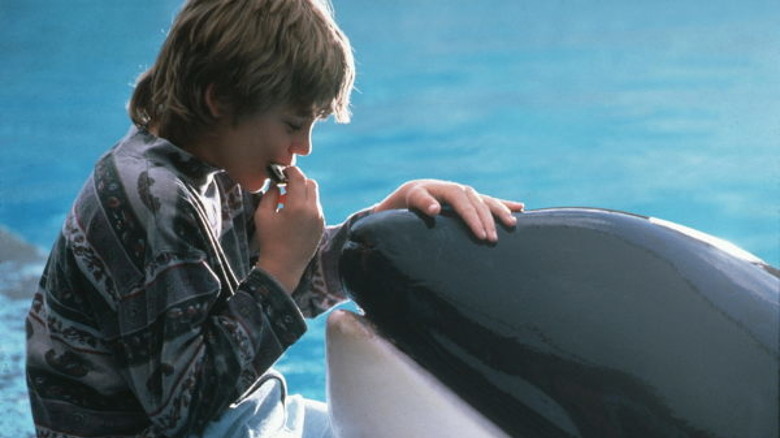

In this film, the young foster kid Jesse (Jason James Richter) is assigned to work at an Oregon aquarium he vandalized. There, he befriends Willy, the park's star orca. When the park's owner Dial (Michael Ironside) tries to kill Willy for the insurance, Jesse spearheads an effort to free him. The poster depicts the climax, with Willy breaching the water and reaching the freedom of the ocean. It's upsetting that the real story of Keiko, the orca actor who played Willy, was not so happy. Keiko's sad story has been documented both on film ("Keiko: The Untold Story of the Star of Free Willy") and in pages of The New York Times.

Keiko's true story

The opening scene of "Free Willy" depicts the whale's capture; Willy is encircled by fishing boats and ensnared with nets. This is probably close to what happened to Keiko himself when he was captured in Icelandic waters circa 1979. He was bounced around from a local aquarium to Marineland in Ontario to Reino Aventura in Mexico City. That last location is where the "Free Willy" crew filmed him.

As Naomi Rose (a marine animal scientist affiliated with the Humane Society) later told the NYT, "In order to make 'Free Willy,' they had to sort of violate the fundamental premise of the film." However, the film's success brought the spotlight to Keiko's poor treatment at his current home (if you watch "Free Willy" attentively, you can spot Keiko's own lesions on the whale's skin).

This kickstarted a public campaign to free Keiko, as his silver screen self had been. The funds came from institutions like the Humane Society, billionaire activist Craig McCaw, fundraisers by schoolchildren enamored with "Free Willy," and even the film's distributor Warner Bros.

The "Free Willy" sequels were filmed with only animatronic whales, while Keiko was eventually moved back to Iceland in 1998. The problem? Having been captured young, he'd never lived as a wild orca. Take note of his collapsed dorsal fin (shared by Willy), a sign of long-lasting captivity. Rather than being "set free," Keiko was kept in an ocean pen and under observation. His trainer Jeff Foster had to teach Keiko everything from holding his breath to hunting for his food. When he was let out into the ocean, he failed to properly socialize with other whales, despite fruitless efforts to locate his original pod.

Freeing captive whales

The project, which cost an estimated annual $3.5 million, gradually evaporated as funding dried up. So, Keiko's observers shifted to "tough love." That approach seemed to succeed in 2002 when he swam off into the wild, but by September of that year, he was swimming off the Norway coast and making friends with the villagers and fishermen there. It seemed that he'd been reared by humans for too long to ever let go of them.

Keiko ultimately died of pneumonia in December 2003 at age 27, fairly young for an orca (their lifespans are comparable to humans'). Rose would tell NYT that Keiko's reintegration was a "complete failure," but considering he probably would've died even sooner at Reino Aventura, she feels the project wasn't for naught.

Public fascination with orcas has lived on past Keiko. The 2013 documentary "Blackfish," directed by Gabriela Cowperthwaite, focuses on captive orcas' treatment at SeaWorld. Inspired by the death of trainer Dawn Brancheau by the orca Tilikum, the doc interviews past SeaWorld employees and paints a pattern of animal abuse; whales are intelligent and emotional animals, so keeping them confined in small pools can only harm them. Tellingly, the only fatal orca attacks on humans come from captive whales.

The closing moments of "Blackfish" include footage of protestors with "Free Tilly" signs. While Tilikum would die in captivity in 2017, the lawsuit OSHA v. SeaWorld won better protections for trainers. SeaWorld has also phased out its orca shows and is not breeding its current stock.

The Keiko experiment has created doubt over whether captive orcas can be reintegrated back into the wild. However, the Miami Seaquarium announced plans to free its orca, named Lolita, earlier this year. Fingers crossed that she gets a happier ending than Keiko.