Why Star Wars Passed On The Chance To Make Early IMAX History

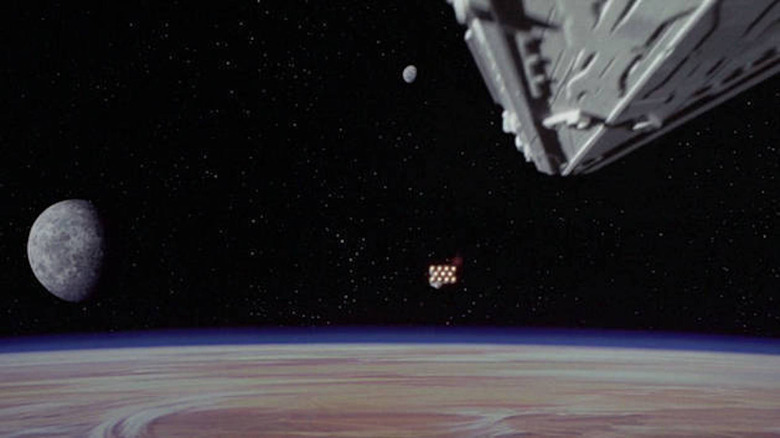

George Lucas' original "Star Wars" was, at the time, probably the most technologically complicated undertaking since Stanley Kubrick took a space-crazed populace for a tour of the galaxy in "2001: A Space Odyssey." The motion control camera pioneered by John Dykstra (which he dubbed the "Dykstraflex") allowed Lucas to pull off the Death Star trench run, which ended the film on a rousing note and changed the medium forever.

But before it became a global sensation, 20th Century Fox didn't get "Star Wars." According to Lucas, Alan Ladd Jr., who greenlit the movie, told the up-and-coming director, 'I don't understand this movie, I don't get it at all, but I think you're a talented guy and I want you to make it.'" His gut instinct was based on the box-office success of "American Graffiti," which was a grounded, night-in-the-life tale of teenagers on the cusp of adulthood. It was relatable. For whatever reason, he trusted that Lucas' gearhead talents would translate into something transcendent.

Ladd was right, but what he didn't know at the time was that Lucas' ambitions almost led him to team with a group of Canadian upstarts who were developing a high-resolution format that would come to be known as IMAX.

Lucas didn't want to push the envelope, he wanted to shred it

For most of his career, Lucas worked ahead of the technological curve. When the technology couldn't meet him at the bleeding edge, he paused the "Star Wars" saga for 16 years until computer-generated imagery caught up with his dizzyingly high expectations.

Lucas begrudgingly shot "Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace" on 35mm before switching to digital cameras for the last two Prequel Trilogy installments. But there's an intriguing what-if as to his preferred exhibition format, one that stretches all the way back to 1975.

Lucas was determined to give moviegoers a one-of-a-kind viewing experience, so he put out feelers to anyone who was developing new cinematic tech. According to J.W. Rinzler's "The Making of Star Wars," this led producer Gary Kurtz to fly to the Great White North and meet with a company that had worked up an ultra-immersive high-def film camera.

Lucas and IMAX were the right combination at the wrong time

This was IMAX, which, in 1975, was a year away from releasing its vertigo-inducing short film "To Fly!" Kurtz was knocked out by what he saw, but there were logistical concerns. As he told Rinzler:

"They were willing to pick up the tab between that and regular 35 millimeter, which could have been half a million dollars. But converting theaters is difficult, and optical effects were next to impossible in that format. Special equipment would have had to be built. It was just beyond us to seriously consider it."

What I'd like to know is if IMAX would've been willing to place their projectors in Cinerama theaters, which weren't big enough to deliver the full immersion that made IMAX features a theme-park sensation in the 1980s. Given that "Star Wars" wasn't "Star Wars" yet, it's unlikely exhibitors would've been interested in upscaling their biggest houses to accommodate a new format. Also, the high-def cameras might've shown the seams of Dykstra's motion capture sequences. The timing just wasn't right.

Now, 46 years later, "Star Wars" movies have been exhibited in IMAX several times but never completely shot on their cameras. If Lucasfilm ever brings the series back to cinemas, maybe this will change. For now, "Star Wars" is a streaming franchise, which just feels wrong.