One Of The Twilight Zone's Loneliest Episodes Was Inspired By A Real NASA Experiment

What if you woke up alone, only to find that you were the only one in a completely deserted town? While the loneliness might be bearable, the mounting paranoia of being silently watched by those who cannot be perceived would gradually consume you from within. Even the most psychologically sound folks would hurtle toward acute hysteria, as the terror of being alone, yet being secretly perceived in an abandoned setting is a uniquely human one.

Writer Rob Serling captured this unutterable fear in the pilot for his explosively popular sci-fi-horror anthology show — one which aimed to touch upon psychological fears surrounding the Cold War. The show, "The Twilight Zone," would forever alter how this genre was perceived on the small screen, and inspire countless shows that shared a DNA with Serling's intriguing stories. The pilot, titled "Where is Everybody?" effectively set the tone for such an anthology series that delved deep into the layers of the human psyche and dared to ask uncomfortable, yet pertinent questions about free will, conformity, state surveillance, and alienation.

"Where is Everybody?" anticipated the anxieties surrounding the space age, and in particular, man's ambitions when it came to landing on the moon. The uncertainty inherent in this subject evolved into the episode's emotional crux, helping capture the sheer terror of a future shrouded in doubt. However, the inspiration for this episode seems to be rooted in an actual NASA experiment that bred feelings of isolation and paranoia. Let's look into what happened, and how Serling's pilot helped set the precedent for influential television that mirrored the anxieties of everyday reality of the times.

Abject alienation

The episode was broadcast on October 2, 1959: a time when Cold War sensibilities were at breaking point, and humankind was on the precipice of scientific breakthrough and curiosity. With technological and scientific advancements come key cultural changes, which are often, and understandably, met with doubt and resistance before these fresh chapters can run their course. Humanity's ambition to land on the moon now seems like an inevitability, but at the time, this dream felt like an Icarus-like overreach, an exercise in hubris when it came to achieving the impossible. Thus, when Serling's episode dropped, it generated feelings of awe and terror and ended up predicting the Apollo 11 moon landing that occurred almost 10 years later.

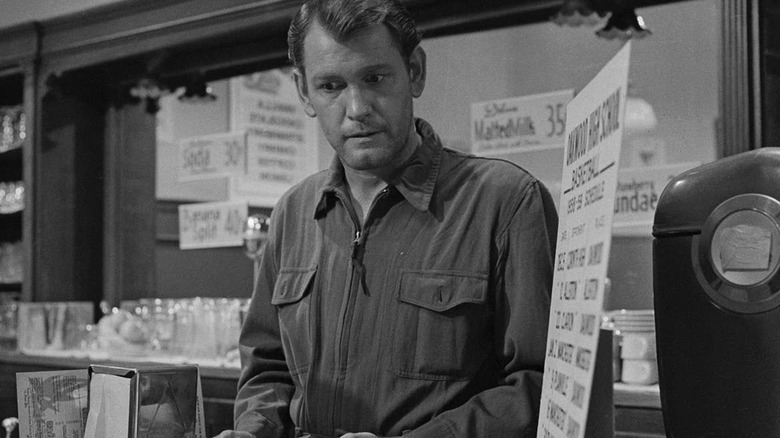

A Time article titled "Rehearsal for Space" detailed an isolation-chamber experiment with airman Donald Farrell, where a 7-day simulation of a trip to the moon and back helped denote such a journey's toll on the human psyche. Farrell was put through certain trials to test optimal conditions required for successful travel, and the airman was able to complete the 7-day stint without any major hitches, be it physical or psychological. Serling seemed to have been inspired by the documentation of this experiment (via The New York Times), which formed the base of his pilot, where an amnesiac (Earl Holliman) stranded in a deserted town is later revealed to be on a simulated trip to the moon and back, a journey which almost breaks his mind and soul.

Just like in the actual experiment, Holliman's character was connected to tubes that monitored his bodily metrics. While Farrell was able to endure the simulation whilst being self-aware, Holliman's character questioned his perception of reality and his place in the world around him.

Hey! Where is everybody?

The key to understanding the Air Force sergeant's experience in "Where is Everybody?" is the susceptibility of the human brain to crumble after isolation for more than 400 hours of recorded time. The sergeant must have entered the chamber with an acute awareness of the trip simulation, but the pressure of these unique circumstances, coupled with mental exhaustion, caused him to eventually hallucinate a reality that helped rationalize this unnatural loneliness. Irrespective of individual preference for isolation, mankind thrives on human connection of some kind to be able to function in certain capacities — a completely isolated round trip to the moon and back definitely breaks the accepted patterns and thresholds of human interaction and lack thereof.

While it is possible for humans to isolate for extended periods without collapsing under the weight of such an existence, the effects on the mind and the soul are worth considering. Add the paranoia of being watched to the mix, and the episode serves up a heady concoction of hysteria and vulnerability, where both isolation and the fear of being perceived work against each other to drive the subject to the brink of breakdown. Serling talked about capturing this sense of nightmarish desolation mixed with anxious wariness:

"I got the idea while walking through an empty lot of a movie studio. There were all the evidences of a community — but with no people. I felt at the time a kind of encroaching loneliness and desolation, a feeling of how nightmarish it would be to wind up in a city with no inhabitants."

As for the moon landing 10 years later, it marked a giant leap for mankind, which was neither a dream nor a nightmare, but a stark, objective reality. Thankfully, by then, we were no longer in The Twilight Zone.