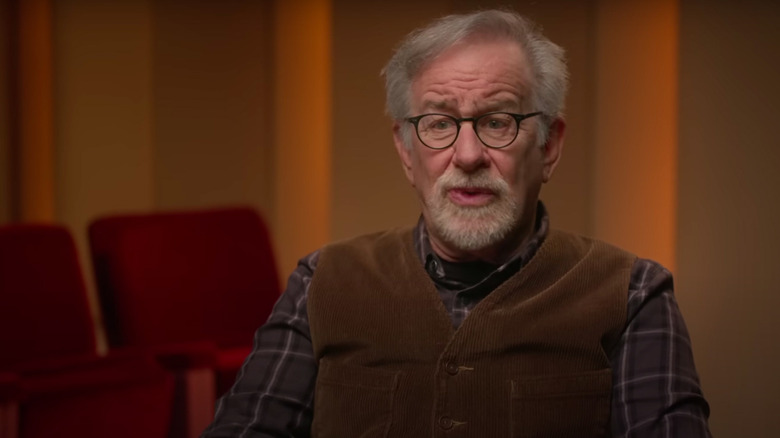

Raiders Of The Lost Ark Had Steven Spielberg Doing Things He Swore He Wouldn't Do Again

In 1981, Steven Spielberg admitted that filmmaking was a learning experience ... in what you hate. Spielberg's first feature was "Duel," a horror movie based on a short story by Richard Matheson, and it was made on a budget of only $450,000, cheap even for 1971. He followed that with "The Sugarland Express" in 1973, a crime thriller that he made for only $3 million. Next came 1975's "Jaws," one of the biggest movies of all time, produced with a budget of $9 million. One can already see the pattern at work. Spielberg started small, and his productions only got bigger and bigger over the years. It wouldn't be until "The Color Purple" in 1985 that Spielberg would break out of his reputation as a maker of mere blockbuster entertainments.

Spielberg never set out to achieve that kind of growth. Indeed, hearing him talk about it, Spielberg always wanted to make multiple small, intimate movies in between the gigantic genre pictures. every time he made a gigantic movie, he would swear to himself that he'd never work at that scale again. Sadly, he was so skilled and enthused at the blockbusters that he was drawn back to that sort of material time and time again. Every time he thought he was out, they kept dragging him back in.

In the November 1981 issue of American Cinematographer Magazine, Spielberg wrote an article, outlining his experience making "Raiders of the Lost Ark," wherein he explained that "Raiders" was essentially the "last time" for him. He regretted not going small and was not going to make giant studio pictures anymore. The existence of "E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial" contradicts this ambition, but Speilberg was determined to downscale eventually.

'And I wound up smack dab in the middle of it again with Raiders of the Lost Ark'

"Every movie has surprises," Spielberg wrote. "You can make all the 'Jaws' and 'Star Wars' in the world, but every special effects movie has something in it that teaches you something you probably wouldn't want to do again." Because Spielberg was so ambitious with special effects and the visual limits of cinematic storytelling, he admirably pushed himself, but it was often into places he didn't enjoy. He got the shots he wanted, but he found that it was difficult, grueling work in a lot of cases. Why did it all have to be servos and matte paintings and outsize cameras? When would the personal picture come? The filmmaker wrote:

"I keep saying to myself, after I finish a massive production, that I'm going to make my 'little movie,' and I never have. I said it after 'Sugarland Express,' which was massive in its day and its own scale. After 'Jaws,' I said I would never go underwater and work with anything with pneumatics or hydraulics; and after 'Close Encounters' I said, 'That's it with 70mm and optical effects and matte paintings.' After '1941' I said, 'No more miniatures and no more multiple storylines.' And I wound up smack dab in the middle of it again with 'Raiders of the Lost Ark.'"

Spielberg didn't expand on what kind of "little movie" he wanted to make, but he clearly had ambitions beyond the enormous. With the exception of "The Color Purple," an awards darling unto itself, even Spielberg's prestige pictures were epic productions. "Empire of the Sun" cost more to make than "Raiders of the Lost Ark," and even "Always" was more expensive. One might say that Spielberg wasn't permitted to "scale back" until 2002's "Catch Me If You Can."

When big filmmakers want to work small

Some filmmakers, perhaps regrettably, become industries unto themselves. Michael Bay doesn't necessarily want to make explodey "Transformers" movies, but each one of those pictures keeps thousands of people employed. George Lucas could have likely made the intimate experimental movies he wanted to after making "Star Wars," but he was such a massive celebrity in the industry, that he likely never saw a time window when it was plausible.

Spielberg is a massive power player in Hollywood, going all the way back to the beginning of his career. Some of his films were bombs, but for the most part, he was widely embraced and encouraged by studios and the Hollywood system in general. His struggles, then, are massively different from ambitious filmmakers with no budgets, working independently, and making movies for the sheer love of the craft. Spielberg, it seems, worked through that era of his life as a teen, shooting movies with friends out in the desert (a process that was dramatized in Spielberg's 2022 film "The Fabelmans"). He never had the opportunity to film commercial releases that he shot by the seat of his pants. Steven Spielberg is no John Waters.

It wouldn't be until the mid-2000s that Spielberg could use his well-deserved clout to pursue relatively smaller, more intimate stories with powerful political commentary. His 2005 film "Munich" was made for much cheaper than "War of the Worlds" and "Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull" which he made on either side of it. His best movies of recent vintage — "Lincoln" and "The Post" — were not massive blockbusters but had something salient and immediate to say about modern American politics.

It took a long time, but Spielberg finally seems to be away from the filmmaking that gives him a headache.