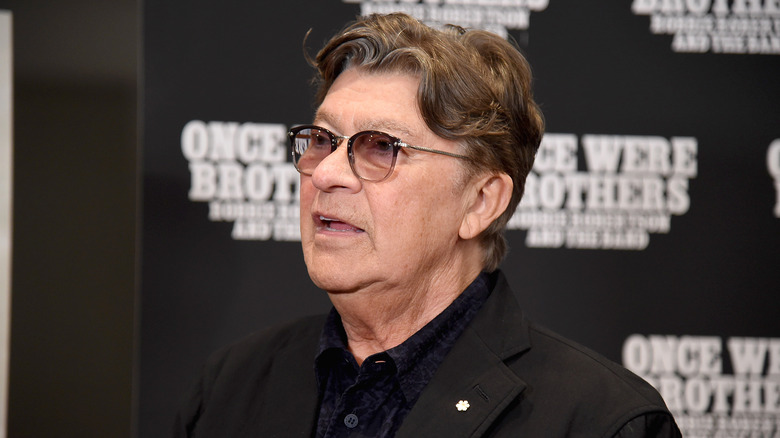

Robbie Robertson Was A Musical Legend — And The Star Of A Martin Scorsese Classic

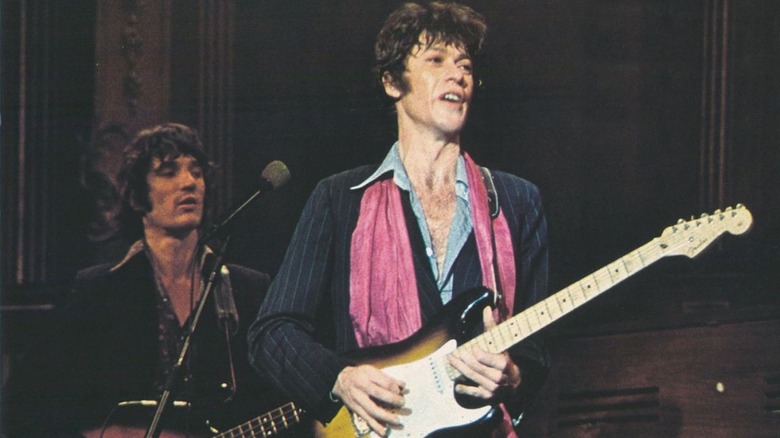

Robbie Robertson found his faith and purpose on the radio. Born and raised in Toronto, Ontario, this child of jewelry-plating factory workers discovered rock-and-roll via the AM airwaves of WKBW out of Buffalo, New York, and fell hard for the blues in the wee hours when WLAC deejay John R. blasted the 12-bar gospel into his bedroom from the far-off music mecca of Nashville, Tennessee. His path was set, and it brought him to rowdy rockabilly artist Ronnie Hawkins, who was impressed enough with a teenage Robertson's guitar acumen to bring him on as a member of his backing band The Hawks. In the early 1960s, Robertson formed a bond with singer/bassist Rick Danko, singer/pianist Richard Manuel, multi-instrumentalist Garth Hudson, and singer-drummer Levon Helm.

It's here that these five, brilliantly talented rock-blues aficionados formed The Band.

Robertson, who passed away today at the age of 80 after a long illness, was The Band's locomotive. He wrote many of their most celebrated songs, including their breakthrough "The Weight" (featured prominently in Dennis Hopper's New Hollywood jump-starter "Easy Rider") on "Music from Big Pink," and sought the spotlight when the group teamed with director Martin Scorsese for what many consider the greatest rock-and-roll concert film in "The Last Waltz." This was The Band's farewell concert and the beginning of Robertson's soundtrack collaborations with Scorsese. He was the Oscar-winning director's trusted needle-drop collaborator. Together, they assembled a vivid aural tapestry that stretched from "Raging Bull" to the upcoming "The Killers of the Flower Moon." Robertson also went on to record a number of solo LPs, where he often explored and honored his Native American heritage.

Robertson was a musical powerhouse. He was also not universally beloved.

What's the game? Cutthroat.

Robertson's camera-friendly charisma in the star-studded "The Last Waltz" irked his bandmates, who felt he diminished their contributions. Helm, whose Arkansas drawl was the vocal highlight of many a Band track, bristled at Robertson being depicted as a backup hero when he was, in actuality, singing into a dead microphone. Helm felt Robertson used his friendship with Scorsese to sideline the rest of the group. He also thought the break-up was premature, that The Band had more tread on their tires after 16 years on the road (and, indeed, they did reunite in 1983 and toured for a time).

Ironically, these internal squabbles have been used to denigrate Robertson when, really, all the guy did was walk away from a group that benefited tremendously from his songwriting and underrated guitar playing. There are gems to be found on "Cahoots" and "Moondog Matinee," but 1977's "Islands" was damning evidence of a group running on fumes. If Robertson's heart wasn't in it, cutting ties and holing up in a Mulholland Drive house with Scorsese wasn't the worst idea — save for the massive amounts of cocaine the duo, by their own admission, inhaled.

Scorsese's health declined tremendously during this period, but both men ultimately pulled out of their blow-fueled tailspin and began a musical partnership that defined the art of the needle-drop music cue.

A shared love of the 20th century popular songbook -- and beyond

The brief Robertson-Scorsese cohabitation proved, in the long run, spiritually and artistically nourishing. "[Scorsese] turned me on to so many movies," said Robertson in a 2019 Vulture interview, "And I tried to turn him on to some wonderful music that he wouldn't have discovered on his own." They each had their own strengths: Scorsese was big into '60s girl groups and the Rolling Stones before he hooked up with Robertson (his use of The Ronettes' "Be My Baby" and the Stones' "Jumpin' Jack Flash" in "Mean Streets" were uniquely propulsive at the time), while Robertson had an ear for the blues and, as he told Vulture, newer stuff like the Dropkick Murphys' "I'm Shipping Up to Boston" in "The Departed."

Their masterpiece is, unquestionably, "Goodfellas," which strings together such sonically diverse tracks as Otis Wilson and the Charms' tuneful "Hearts of Stone." Jerry Vale's ballad "Pretend You Don't See Her," Donovan's goofily mystical "Atlantis," The Ronettes' seasonal Wall-of-Sound classic "Frosty the Snowman," Derek and the Dominos' Duane Allman-captained bridge to "Layla," Nilsson's rollicking "Jump into the Fire," Devo's anxious cover of "Satisfaction," and, finally, Sid Vicious' "My Way" as if they were always meant to be together. It's a demented jukebox run that feels like two music lovers trading favorites — corny, obscure, and downright bizarre — in the diviest of dive bars.

And, yes, their in-film pièce de résistance was Larry McConkey's Steadicam gliding through the Copa's side entrance to The Crystals' "Then He Kissed Me" (even if the song had been previously featured over the opening credits of Chris Columbus' "Adventures in Babysitting").

A great musician, and, perhaps, a greater music lover

Robertson wrote scores for Scorsese, too, and feared his buddy had betrayed him when he plugged his unfinished musical sketches straight into "The Color of Money." This was just Robertson riffing motifs in his studio. He was hopping from instrument to instrument and humming melodies. Scorsese felt this rough noodling matched the film's gritty aesthetic to a tee, and Robertson agreed.

Robertson's work syncs up well with the film's poolhall needle-drop, which mashes up blues classics from Willie Dixon and B.B. King with Warren Zevon's all-timer "Werewolves of London." I don't know who selected what track, but it stinks of booze and bad choices. It's sleazy perfection.

Robertson lived that life early in his career. He heard it on the radio, sought it out, and brought it to us with a Canadian inflection. He wasn't a good singer, and maybe wasn't the best bandmate on a personal level, but, goddamnit, he was a great musician and a genius aficionado. He was as much a teacher as a musician. I grew up listening to The Band, and, trust me, I wouldn't have become obsessed with Muddy Waters were it not for the bluesman's indelible performance of "Mannish Boy" in "The Last Waltz." Robertson made that happen and inspired one of the greatest filmmakers in the history of the medium to blow out his musical palette.

Robbie Robertson was vital. So throw on "The Last Waltz" tonight, and do as you're instructed at the film's outset — play it loud.