A Classic James Bond Film Got Some Secret Assistance From Stanley Kubrick

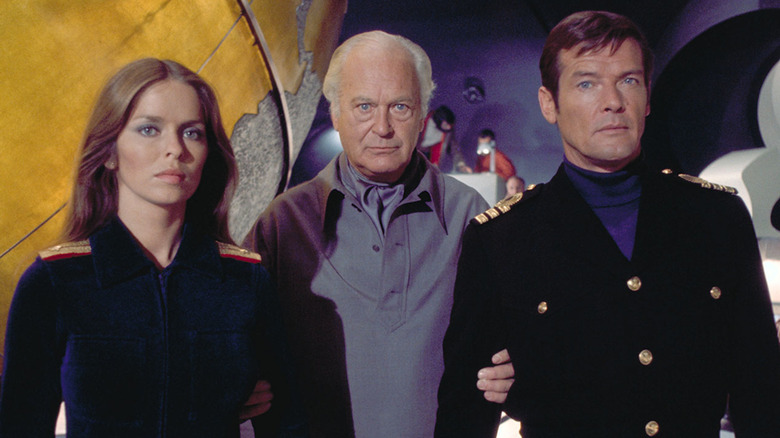

1977's "The Spy Who Loved Me" is a landmark James Bond film for several reasons. For one, it fully cemented Sir Roger Moore as Bond, establishing his take on the character as distinctive and separate from Sean Connery and George Lazenby. For another, it introduced another recurring character to the continuity-lite franchise: Richard Kiel's imposing (and mostly silent) henchman, Jaws. The film also featured a then-groundbreaking stunt sequence, a buzzworthy moment that helped it become the massive box-office hit the franchise needed in order to continue at all after the underperformance of "The Man With the Golden Gun."

Most intriguingly for the spy movie in general, however, "The Spy Who Loved Me" introduced the notion of detente between Her Majesty's Secret Service (represented by Bond) and the KGB (represented by Barbara Bach as Anya Amasova). This spirit of tolerance and occasional cooperation continued throughout the next several Bond films, and seemed to indicate a general desire in the culture for the long-running Cold War to finally be over. As in many a good drama, it's a kick to see Bond get an assist from an unlikely ally.

In the way life often imitates art, that's exactly what happened behind the scenes of "The Spy Who Loved Me," too. Well, sort of: When production designer Ken Adam and cinematographer Claude Renoir ran into an issue while struggling to light the centerpiece set of the film — the interior of the villain's massive floating submarine dock — they received an assist from none other than photographer extraordinaire (and, oh yeah, film director) Stanley Kubrick.

Adam and Renoir struggle to let there be lights

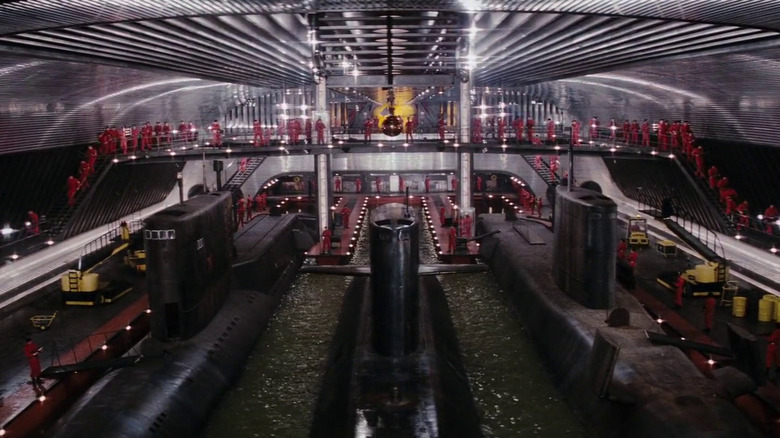

Although Eon Productions' first Bond film, "Dr. No," included an elaborate hidden base for its villain, the next few Bond movies were a little more lowkey. That changed with 1967's "You Only Live Twice," which saw Bond's nemesis Blofeld establish a giant rocket base inside an active volcano. From there, each subsequent Bond movie attempted to one-up its predecessor, and "The Spy Who Loved Me" is no exception: Not only does the film's villain, Karl Stromberg (Curt Jürgens), run an elaborate ocean-bound hideout known as the Atlantis, he also commands the supertanker known as Liparus, which has been constructed to capture nuclear submarines from both the British and the Soviets.

Building the massive set for the interior of the Liparus required Ken Adam to erect an entire new soundstage on the Pinewood Studios lot, the water tank-equipped building that would subsequently be known as the 007 Stage. Although the construction of the set was a feat in and of itself, lighting the set was another matter entirely. As Claude Renoir explained in Matthew Field and Ajay Chowdhury's 2015 book "Some Kind of Hero: The Remarkable Story of the James Bond Films:"

"That set is completely closed on top and we show the ceiling in most of the shots, so the problem is the same as it is in some real-life locations — no place to put lights, without showing them in the picture. There is no room for big lamps, so I am using a lot of very small lamps."

Yet Adam hoped for the set to be much more dramatic for its initial reveal, as he explained:

"On this big set we have a major light change. When the submarine enters the set it is in relative darkness, and then the lights go on and expose the whole set."

Nobody does it better (than Stanley Kubrick)

Fortunately, this dilemma reminded Ken Adam of working for Stanley Kubrick on "Dr. Strangelove" a decade and change prior. During that experience, Kubrick changed Adam's views on lighting a set:

"To my way of thinking, when Claude [Renoir] kept the set dark it looked more dramatic than when all the lights went on. Hopefully, I give cameramen the elements to compose on and to create dramatic lighting. I think that's much more important than seeing every little detail. In my earlier days as a designer, I tried to make it possible to see every detail of the set, and the first person who really said I was wrong was Stanley Kubrick. He knows a lot about photography and I had to agree with him."

Adam, who'd recently served as Kubrick's production designer for "Barry Lyndon" just a year earlier, surreptitiously called up the director for help with lighting the Liparus. Adam recalled how Kubrick had to be convinced to show up, not wanting to accidentally undermine or insult Renoir:

"Stanley thought I had gone mad. I said, 'Stanley, I will organize that you and I are the only people there on a Sunday. All we do is walk through the stage and if you have any ideas I'll be very grateful."

Sure enough, Kubrick did have an idea: To build floodlights in as part of the Liparus set, thereby allowing for the dramatic "major light change" effect Adam wanted.

Another Kubrick is responsible for Jaws' jaws

That lighting of the Liparus set isn't the only Kubrick family contribution to "The Spy Who Loved Me," however. Stanley Kubrick's daughter, Katharina, designed the famous teeth that make the character of Jaws earn his colorful moniker. According to Matthew Field and Ajay Chowdhury, producer Albert R. Broccoli rejected an initial design by the likes of makeup man John Chambers, who had designed the iconic ape makeup for "Planet of the Apes."

Katharina Kubrick instead designed special dental fittings for Richard Kiel to wear, which Broccoli recalled the actor could only keep in "for a certain length of time." Despite this, the design was approved by both Kiel and Broccoli, allowing the character of Jaws to join the ranks of Bond henchman history.

Thus, thanks in part to the Kubrick family, "The Spy Who Loved Me" gained a remarkable set and a memorable character, both of which added to the movie's overall lasting effect on Bond films and cinema in general.