Why Khan Noonien Singh Casts A Shadow Over The Entire Star Trek Universe

According to its own mythology, the utopia of "Star Trek" had to be earned. Sometime between the present day and the franchise's idyllic future, several destructive wars will break out, causing humankind to experience a reckoning. Recall that Trek creator Gene Roddenberry was born in 1921, so he had very sharp memories of World War II and all of the horrors it produced. Roddenberry came to feel that humanity ought to learn from such horrors, and began to depict war — at least in "Star Trek" — as humanity's "low point." Once faced with self-destruction, Roddenberry felt, humans would eventually set themselves on the path to healing and recovery.

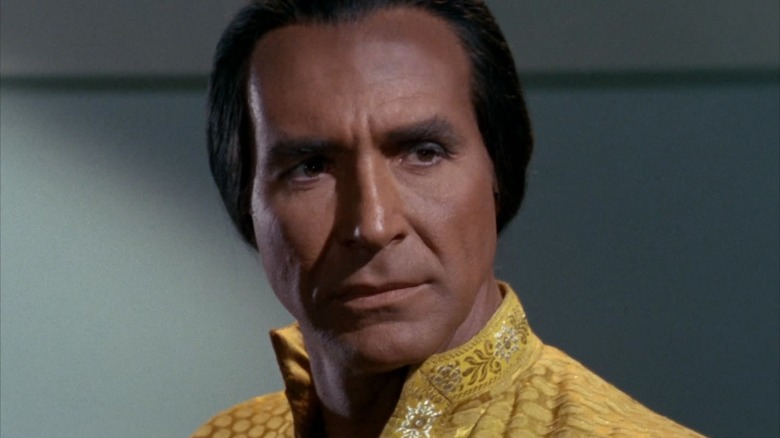

It was antithetical, then, for Roddenberry to depict the character of Khan Noonien Singh (Ricardo Montalbán) the way he did. In the "Star Trek" episode "Space Seed" (February 16, 1967), the Enterprise rescues Khan from a cargo ship called the Botany Bay. Khan and several of his compatriots were in cryogenic sleep, having fled Earth about 200 years previous, fleeing extradition. Khan, you see, was one of Earth's most famous dictators during the Eugenics Wars. He had conquered most of the planet with the aid of his genetically enhanced retinue. Khan was confident, forthright, and convinced of his innate superiority, qualities that — bafflingly — Kirk (William Shatner), Spock (Leonard Nimoy), and the ship's historian Lieutenant McGivers (Madlyn Rhue) greatly admired.

"Star Trek" may have been a pacifist show at its heart, but too often the characters stood in unironic awe of violent military commanders. McGivers especially folded to his charms. It was a little gross.

Although Khan left the show after "Space Seed," he would return in cinematic form. From 1982 onward, Khan would alter "Star Trek" forever, both for better and for worse.

The impact of Khan

In "Space Seed," Khan, seeing an opportunity to begin his old nation-conquering habits again, tried to take over the Enterprise. Kirk and Spock outwit him, knock out his genetically enhanced retinue, and wrest back control of the ship. Rather than punish Khan for his malfeasance, however, Kirk gives the villain an ultimatum: can he create the ideal society he's always dreamed of on an uninhabited planet somewhere? Khan accepts the challenge, and he is left on a planet called Ceti Alpha V to build his masterpiece society. Khan was out of sight and out of mind.

Until the release of "Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan" in 1982. In the film, it was revealed that shortly after Khan arrived, Ceti Alpha V experienced a massive natural cataclysm that transformed it into an inhospitable desert world. For decades, Khan and his retinue lived huddled in a ship, barely surviving, growing increasingly preoccupied with getting revenge on Kirk. Over the course of "Star Trek II," Khan commandeers a Starfleet vessel called the U.S.S. Reliant and goes hunting for Kirk, now an admiral. Kirk, meanwhile, is going through a midlife crisis wherein he finally faces the consequences of several forgotten transgressions. Khan is the personification of Kirk's absent-mindedness; he never bothered to check in on Khan.

Popular opinion typically dictates that "Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan" is the best of the 13 extant "Star Trek" movies. Montalbán brings a glorious, melodramatic oomph to his performance that thrills audiences and handily balances Shatner's occasional tendency to play Kirk as larger-than-life. He is a great "Star Trek" villain.

But then, that's a problem. Since when was "Star Trek" about "heroes" and "villains"? Since 1982, it seems. Ordinarily, Trek is more morally nuanced than that.

Moral absolutism

Throughout its history — and throughout the 1990s in particular — "Star Trek" writers have often bent over backward to present dramas with a palpable element of moral ambiguity. It's rare that a character will be presented as wholly heroic or villainous, as that's not true to life; heroes and villains don't exist. Only people. People of all walks may commit acts of heroism, or even acts of villainy, all the while convinced that what they're doing is right and correct. "Star Trek" analyzes human values and philosophies, and attempts to find a careful middle ground within a matrix of diplomacy and pragmatism. Justice and morality are more nuanced than "good" vs. "evil." In Trek, conflicts are rarely solved by a hero besting a villain in violent combat. That's "Star Wars" stuff.

But, it cannot be denied that such conflicts are exciting, easy to consume, and imminently cinematic. On TV, Trek could afford a slower pace and episodes that centered on conversation and philosophy. On the big screen, however, everything needs to wrap up more dramatically and tidily. As such, most of the "Star Trek" movies are a lot more action-forward than anything on TV. And when the franchise discovered the effectiveness of Khan as a "Star Trek" supervillain, they hit a groove. A charismatic villain who wants personal revenge on a Starfleet captain? Bully! Let's do that as often as we can get away with. Also, more shooting and yelling and space battles and explosions.

By the early 1990s, a fan consensus began to form around the first six Trek movies, and many agreed that "Wrath of Khan" was the best. The franchise soon began to imitate it, looking for their next Khan.

The revenge quartet

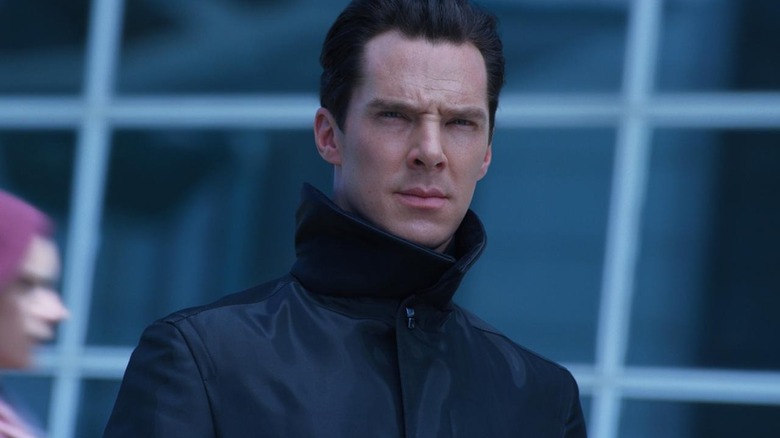

It's telling that four Trek films in a row — "Star Trek: Nemesis," the 2009 film, "Star Trek Into Darkness," and "Star Trek Beyond" — all centered on vengeance-obsessed villains. The third season of "Star Trek: Picard" also retreaded the concept. In "Nemesis," Shinzon (Tom Hardy) wanted to kill Captain Picard (Patrick Stewart) because he was cloned from Picard's DNA. Shinzon's ship and the Enterprise-E ended the film facing off in a nebula, just like in "Wrath of Khan." In the 2009 film, a Romulan named Nero (Eric Bana) sought revenge on Spock. In "Darkness," Khan was resurrected in a parallel universe form, played by Benedict Cumberbatch. He still wanted revenge. "Beyond" was about Kroll (Idris Elba) a man who came to hate being abandoned by the Federation — just like in "Wrath of Khan."

And "Picard," made 41 years after "Wrath of Khan," still followed a lot of the same beats. Vadic (Amanda Plummer) was a dark, vengeful villain with an overpowered ship. "Picard" even went so far as to borrow music cues directly from "Khan" to invite comparison.

Again: a supervillain is a dramatically satisfying archetype, especially in your typical Hollywood melodrama. Their villainy is easy to understand, and the means to stop them clear (usually violence). Seeing a bad guy get murdered is cathartic. But seeing Khan as a "villain" was the wrong lesson to have taken from "Star Trek II." In a more sane Trek plot, Kirk would find a way to give Khan what he wanted and talk his way out of the problem. The villains in all the above movies have legitimate grievances, and TV "Star Trek" would spend more time addressing and repairing said issues.

Khan's shadow is long, and his legacy is simultaneously fun and very, very unfortunate.