The Most Important Moment In Oppenheimer Dismantles One Of America's Greatest Lies

Spoilers for "Oppenheimer" follow.

The cast of "Oppenheimer" is populated by historical figures, but one of the most recognizable is in the movie for only a single scant scene.

A stretch in the middle of the film takes place in 1945 when the Manhattan Project is on the cusp of completing the bomb while the war they were building it for winds down. As you probably know, the U.S. shifts its target from the defeated Germany to the still-standing Japan. J. Robert Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy) wants the post-war atomic policy to be global cooperation; he hopes that President Harry Truman will loop in Joseph Stalin about the atomic bomb to bring the U.S. and Soviet Union together on the issue. The Trinity explosion test at Los Alamos Labs is even moved up to accommodate Truman's schedule.

Oppenheimer learns as the bombs are carried off that Truman didn't tell Stalin as he'd hoped. Then, he only gets face-to-face time with the President after the bombs are dropped. Truman is played by none other than Gary Oldman, hidden behind saggy make-up, a thin white combover, and Truman's Missouri drawl (this isn't the first time that Oldman has played a leader of the World War II Allies).

Truman and Oppenheimer's meeting, set in the Oval Office and hewing closely to the word of the source biography "American Prometheus," puts Oppie on the path of penance that he takes for the rest of his life. It's also crucial to understanding what "Oppenheimer" is saying about the bomb.

Oppie meets Truman

When Oppenheimer meets Truman, he's still shaken by the body count of his creation. Truman, though, is genial and boastful about having bombed Hiroshima — he's forgotten about Nagasaki altogether. Oppenheimer turns the topic to the Soviets, but Truman, with prideful ignorance, declares that Russia will never have a nuclear bomb. His mood only sharpens when Oppenheimer suggests giving Los Alamos back to its indigenous inhabitants. No, the U.S. military will keep the lab active to shepherd further weapons development.

Oppenheimer finally admits that he has blood on his hands and Truman's contempt explodes. He waves a handkerchief in Oppie's face, calling his regret out as arrogance — the Japanese only care about he who dropped the bomb, the Commander-in-Chief declares. "Oppenheimer" was shot in IMAX, but Nolan's alternating close-ups of Murphy's and Oldman's faces feel as confined as a 4:3 frame and trap the audience in the discomfort of the conversation.

Oppenheimer is escorted out of the Oval Office and overhears Truman ordering that the "crybaby" never be allowed in his presence again. In real life, Truman actually called him a "f***ing cretin."

Now, some might be glad that Oppenheimer receives no sympathy; thousands died because of his creation, so his regrets can only feel like crocodile tears. However, Truman's reaction suggests an unflattering truth about him, one that's contrary to the mythmaking of his legacy.

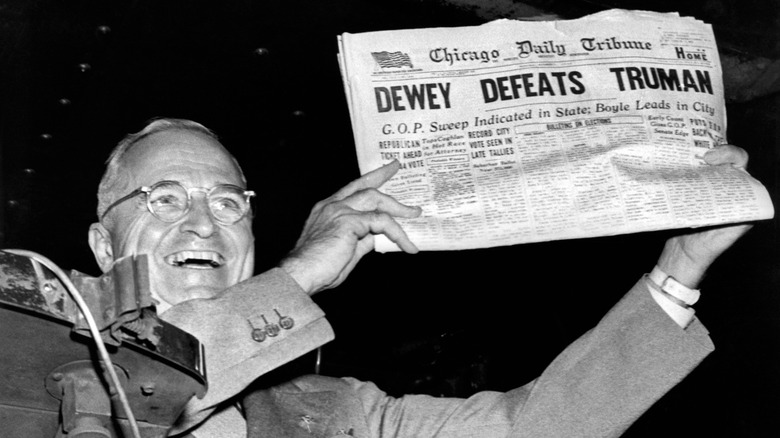

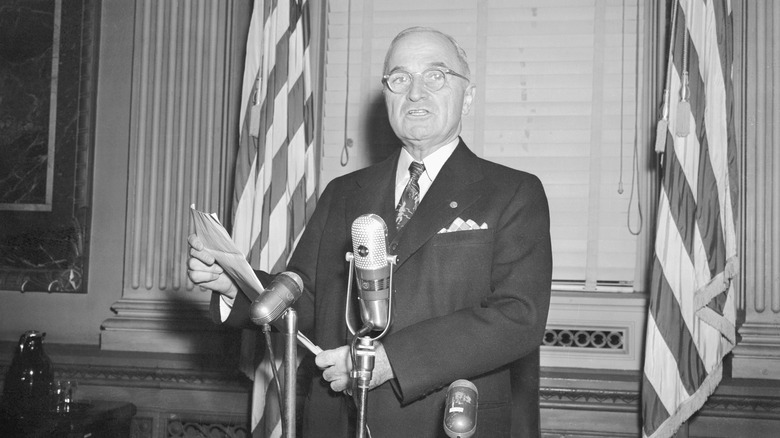

The Real Harry Truman

Americans are generally taught that the U.S. nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were the lesser of two evils. After all, they brought World War II to a swift close. If the bombs hadn't been dropped, then the U.S. would've had to launch a ground invasion and even more people would've died, since the Japanese would not have surrendered otherwise. Truman ordering the bombing was an impossible decision, one that he took upon himself like Christ on the Cross. "Oppenheimer" shows the truth.

Harry Truman didn't drop the bomb because he was forced to. He dropped it because he wanted to and was proud of the decision to his dying day. Sure, maybe he did believe that his actions ultimately saved more lives than they cost. But that's not all. Part of the motive was payback for the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941; Truman's original press release notes the Japanese have been repaid "manyfold."

In "Oppenheimer," it's suggested that the bombings of Japan weren't just the end of World War II, but the start of the Cold War. Between this and Truman's own depiction, the argument in "Oppenheimer" is that Truman wanted a dramatic demonstration of America's power on the world stage, as he was convinced that the atomic bomb would make his country undisputed master of the post-war order. However, what he really accomplished was kickstarting the arms race with the Soviet Union, who naturally feared nuclear bombs being turned on them.

Thoughts from a post-nuclear world

The merit of Truman's decision has been questioned more and more as time gets further away from it. Many contest the very crux of the pro-bomb argument — that there was no other way — on not just moral grounds, but factual ones.

As "American Prometheus" details, the Japanese were considering surrender before the first bomb was dropped on August 6, 1945. The Soviets were preparing to join the Pacific theater and the full force of the Allies would have doomed Japan. So, the Japanese reached out to the USSR to act as a possible third party in peace talks. The U.S. moved up the Trinity test and bombings before those peace talks could happen since they didn't want to miss the window to show off their new toy. This shows the dark side of Truman's ethos that "the buck stops here," or that costly decisions were his responsibility and his alone.

"Oppenheimer" doesn't absolve its eponymous subject, but it definitely sides with his later view; that by giving humanity atomic bombs, he gave us the ability to destroy ourselves. The world would be better off if nukes weren't in the hands of gung-ho men like Harry Truman. I think it's important to note that none of the key players in this depiction of Truman are American (Nolan and Oldman are English, Murphy is Irish). Thus, they can look at the 33rd President differently because they weren't taught the same history. "Oppenheimer" might just change some people's minds too.