Honey, I Shrunk The Kids Broke The Bank For Its Backyard Bee Riding Scene

Joe Johnston's family adventure film "Honey, I Shrunk the Kids" was an unexpected hit when it was released in the summer of 1989. Modestly budgeted, the film starred Rick Moranis as an amateur molecular engineer and father of three who has been working on a shrink ray in his attic in his spare time. When his kids are playing around in the attic, they activate the shrink ray and are reduced to a tiny size. They are then unwittingly swept into the trash and carried out to the backyard. The bulk of the film is a trek the tiny kids take across the lawn, climbing enormous stalks of grass, befriending giant ants, and doing battle with monstrous scorpions. "Honey, I Shrunk the Kids" famously played with the first of three Roger Rabbit cartoon shorts, "Tummy Trouble," likely contributing to its success. The film made $222 million worldwide.

"Honey" also spawned several little-talked-about sequels including 1992's "Honey, I Blew Up the Kid," the 1994 Disneyland 3-D short film "Honey, I Shrunk the Audience," and the 1997 straight-to-video film "Honey, We Shrunk Ourselves" (co-written by Joel Hodgson). 1997 also saw the launch of "Honey, I Shrunk the Kids: The TV Series," which lasted for three seasons.

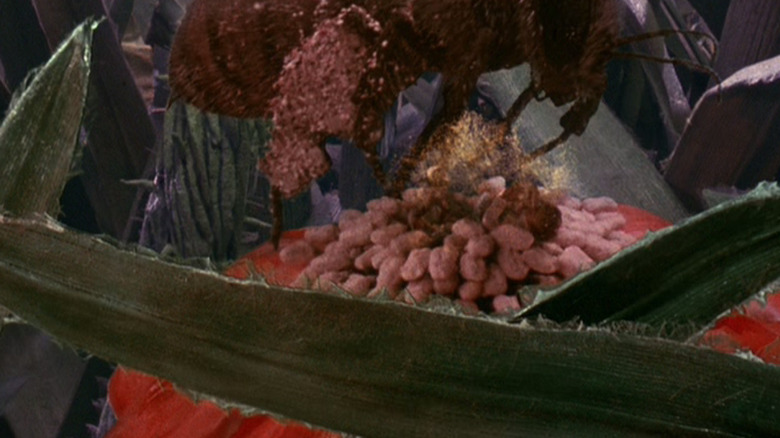

One of the highlights of "Honey" was a scene wherein the kids ride around on the back of a giant bumblebee. As one might imagine, a large portion of the "Honey" budget went to constructing both oversized sets for the shrunk kids as well as miniatures for the normal-sized adults, and the bumblebee involved both. In a making-of documentary broadcast on TV in 1989, the filmmakers explained that they did indeed build an oversized bee for the actors to ride on, but also a very, very expensive animatronic bee with animatronic kids on its back.

Making the bee sequence

The bumblebee sequence involves the young Nick (Robert Oliveri) falling into a flower, only to be savaged by a colossal Apoidea. The bee picks up Nick, and he and another one of the kids go for a bee-back joyride. The effects used to realize this sequence involve some of the analog techniques one might naturally assume. As Tom Smith, an executive producer and the film's effects producer explained, the first step was to get the background footage that was to be composited in later:

"When we filmed it we literally flew a camera around the yard, and with a wide-angle lens in the camera flew through the yard just like the bee would fly through it. Now we had to put the kids on the bee in front of that, and there were two ways that was done. One: we built this giant bee that was big enough for the kids to be on and we laid them on it, blew wind against them, rocked it back and forth, and put them in front of a blue screen. Everything that was behind them when we composite the pictures, in the end, became the plates, became the flight through space."

Filming vehicle-bound characters against a blue screen was common at the time, as was compositing in the background. Synching up the movements of the giant bee and the kids to the footage was a matter of timing and editing. It takes a lot of work, but even a layperson can imagine the work that had to be done to achieve such a look.

The next part, however, is when things got expensive.

The $30,000 bee

Some of the wider shots of the bee were achieved using some pretty cool-looking stop-motion animation.

Not content to merely have closeups of the kids on bumblebee-back, the filmmakers got ambitious and wanted to shoot some wide shots — of the whole bee — as well. Syching the movement of a giant bee and live actors to the swerving pre-shot footage was simple (if perhaps not terribly easy) enough, but mid-shots involved much more involved camera movements. As such, a model of the bee — and the kids — was built to attach to a motion-control camera. Smith even recalls the price tag. He said:

"The rest of the shot has a mechanical bee, a very intricate, expensive, mechanical bee that has joints in it with kid puppets on it that look very accurate and in great detail. This bee that we built probably cost about $30,000, just to build the bee. The kids are probably about $10,000 apiece. So we're not doing it to save money. We're doing it because we can make that bee fly with a motion-control camera in a way that we could never do it with a model of kids on a stage."

The legs of the animatronic kids kicked realistically as the bee-cam flew through tree branches, chairs, and other things seen in the characters' backyard. It looks pretty cool and was exhilarating for kids in 1989.

"Honey, I Shrunk the Kids" recalls a time when Disney was still struggling to find success (it was made prior to "The Little Mermaid") and more innovation was permitted at the studio. Perhaps with the collapse of $300 million blockbusters, they will soon find the next "Honey, I Shrunk the Kids."