The Last WGA/SAG Strike Started In 1960 – And Was Won By A Young Ronald Reagan

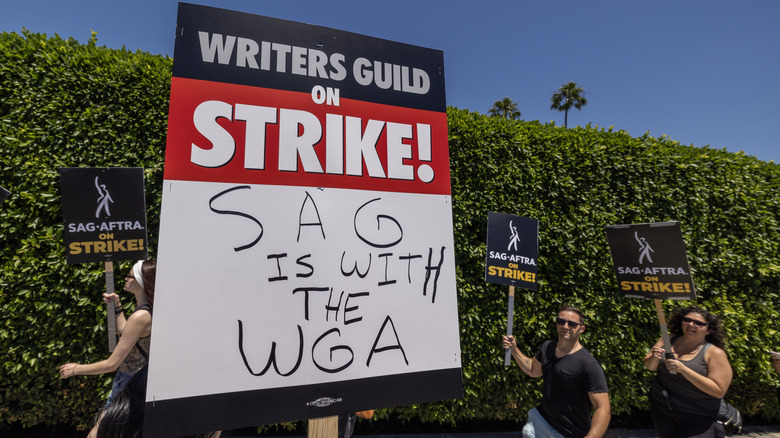

As of Friday, July 14, 2023, SAG-AFTRA (the Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists) is officially on strike. The union's 160,000 members have joined the 11,500 of the Writers Guild of America (WGA) on the picket line where they've been since May 2. Actors and writers stand in solidarity against the appalling greed of Hollywood's corporate bosses, represented by the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP).

To put this in perspective, 1980 was the last time SAG (not yet merged with the AFTRA) staged a full-scale strike — there was a quickly resolved, 14-hour-long strike in 1986 as well. The last time that both writers' and actors' Guilds staged a strike together? 1960.

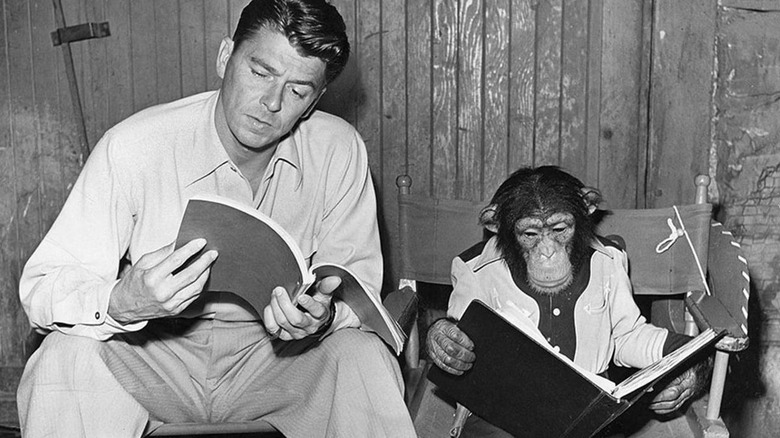

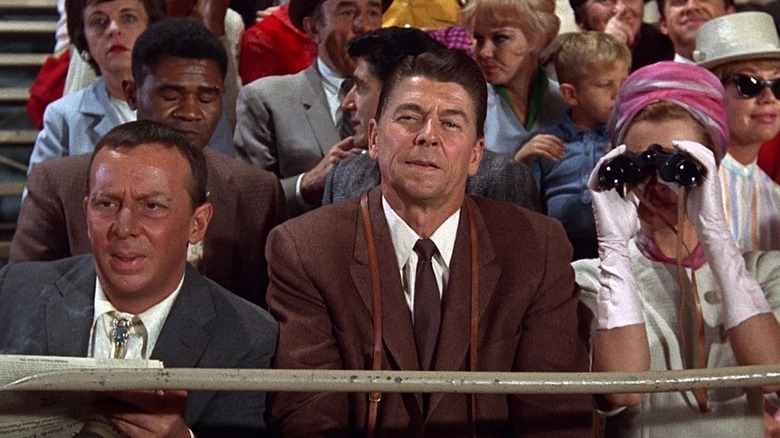

During this strike, the WGA was led by President Curtis Kenyon, writer of a few forgotten Western films and several episodes of early TV hits — "The Long Ranger," "The Untouchables," and more. SAG's President is a name you might recognize though: Ronald Reagan.

Reagan had previously been SAG President from 1947 to 1952, and SAG recruited him for a second term in 1959 in anticipation of a strike. Reagan had close relationships with the producers who SAG was petitioning, such as Lew Wasserman (a power player producer who had been Reagan's agent back in the 1940s), and this made him a valuable negotiator for the actors.

The 1960 strike is generally considered a victory for both unions, with the eventually signed contracts including prosperous residual agreements for writers and actors. How do the stakes compare with today's industrial action?

What was at stake in 1960?

The 1960 Hollywood strike was kicked off by the contemporary industry disrupter — television. By 1960, over 45 million Americans owned a TV set; Hollywood regarded this as an existential threat, rightfully fearing television would steal its audience. The decline of movie theaters has been slow but unending since the advent of home cinematic entertainment.

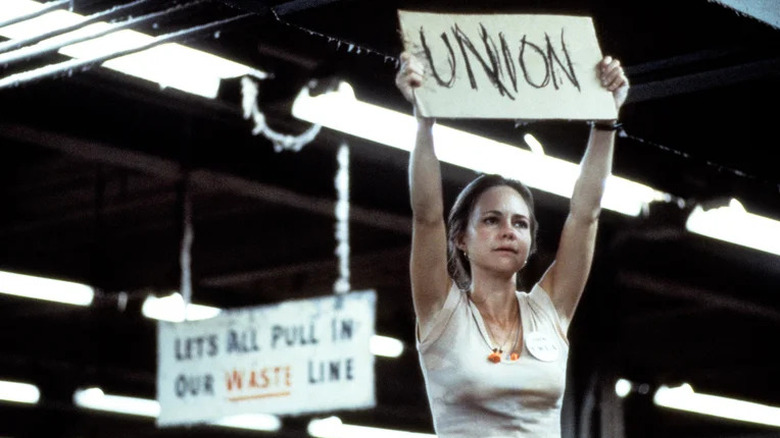

Writers and actors' concern was that if their work was being shown in a new medium, they should be compensated for it. If an episode of TV was aired dozens of times in reruns, shouldn't the writer of that episode be paid for the continued use of their work? While actors had earned residuals from reruns of their TV appearances since the 1950s, films were a different story. If a movie starring, say, Bette Davis was purchased for broadcast by CBS, shouldn't she see a slice of the resulting pie? Producers — not eager to share in their profits — disagreed.

Thus, on January 16, 1960, the WGA called a strike against the Alliance of Television Film Producers (ATFP). SAG followed them on March 7. The 1960 strike lasted a total of 21 weeks. SAG signed a new contract first on April 18, 1960. The actors won residual payments for TV networks' licensing and airing of their movies, though only on films made after 1960. The union also won a one-time payment of $2.25 million, which was used to form a pension and health plan for SAG members.

The WGA stayed on the picket line for two more months until June 12, 1960. The writers' contract granted them both a 4% residual fee for TV reruns and, for movies, a 1.2% cut of TV broadcast license fees to the movie's writer(s). The WGA likewise took financial gains and put them into a healthcare/pension fund for its members. With the ink dry on the WGA contract, the first dual strike in Hollywood history ended.

Reagan, born leader?

Despite the fruits won, there has been criticism of Reagan's leadership of SAG during the strike. Iwan Morgan, author of "Reagan: American Icon," praises Reagan's dealmaking skills but also notes a conflict of interest; Reagan was negotiating against producers despite being one himself. "Reagan kept them out about the fact that he had co-production credits. That only became public knowledge afterward."

James Garner, vice president of SAG during the strike, wrote in his memoir "The Garner Files" that Reagan was more of a spokesperson than a leader: "The only thing I remember is that Ronnie never had an original thought and that we had to tell him what to say. That's no way to run a union, let alone a state or a country."

Reagan's spearheading of the SAG strike is also bittersweet in the wake of his union-busting as U.S. President; by the time he entered politics, he'd left the Democratic Party and turned right due to a lifelong hatred of communism and a stint as a spokesperson for General Electric. SAG was the last entity to weaponize his charisma for progressive ends.

However, the residuals agreements helped secure not just equity, but prosperity for future generations of writers and actors. To this day the cast of "Friends" earn $20 million checks yearly from reruns of the series. Obviously, few TV series are as successful as "Friends," but this is just one example of how residuals can create a nest egg for actors and writers, ones that grant them security in a field that's insecure by nature.

How this strike compares

As it was 63 years ago, residuals are again at the forefront of the dual WGA/SAG strike, brought on once more by a disruption to the entertainment industry's distribution model. Television, the disruptor of yesterday, has been displaced by streaming. Streaming's offered residuals are, putting it lightly, much less equitable than those of old.

Writer Kyra Jones told Reuters that her first residual check for the Hulu series "Woke" was $4 — no, that number isn't missing any zeros. In the model used since the 2008 WGA contract signing, subscriber count at the service is the lynchpin of calculation, not individual viewership of any particular program. There's one reason that streamers like Netflix and Disney+ don't release concrete viewership data to the public.

Furthermore, ever wonder why Netflix shows usually only have 8-10 episodes a season, compared to 22-26 episodes like in old network TV series? Part of it is to lessen residual payouts to writers; if writers are scripting fewer episodes per season, then they're owed less residual money for those episodes. Streaming services have also cut writers' rooms down to "mini-rooms," meaning fewer writers can even get their foot in the door for these meager payouts. It's not just writers bearing the brunt of the streamers' tight-fistedness.

Streaming residuals

If SAG members appear in a streaming program, they are only eligible for residual pay 90 days after it goes live. That is if they get payments at all. A recent exposé in the New Yorker details the residuals earned by the cast of "Orange is the New Black," one of Netflix's earliest successes with original programming. Long story short — their residuals wouldn't even make a blip as an accounting error in Jennifer Aniston's residual payouts for "Friends."

Sydney Sweeney, the breakout star of HBO Max (now Max) projects "Euphoria" and "The White Lotus," told The Hollywood Reporter in 2022 why she can't afford to take six months off work:

"They don't pay actors like they used to, and with streamers, you no longer get residuals. The established stars still get paid, but I have to give 5 percent to my lawyer, 10 percent to my agents, 3 percent or something like that to my business manager. I have to pay my publicist every month, and that's more than my mortgage."

Sweeney may not be not starving, but streaming has made even name actors more precarious. What about actors who people might not readily recognize or writers who never get their faces in front of the camera at all? Mehdi Barakchian, a self-described "middle-class actor," recently told CBS News:

"It used to be such that you could make a living — I'm not talking red carpets and champagne, just the standard American living by working in television as a middle-class actors [...] but the reality is, we can no longer make a living doing that. Something I may have been in [from] 2017, 2018, 2019, would have aired on network television, I would have been able to pay my rent, one day own a home [...] with streaming, and the changes in technology and inflation, none of the current rates [represent] that, we're on much older contracts."

The threat of AI

While streamers have been creating their own new movies and TV for the last decade, they sustain their libraries with existing content — remember, Netflix made its name as a DVD rental company. Studios licensing their libraries to streamers instead of broadcast TV thus undermines actors' and writers' benefits from the original residual models of television, those won in the 1960 strike. As actor Sean Gunn has testified, he's seen almost no residuals from "Gilmore Girls" streaming on Netflix — the show's presence on the platform is also a hurdle to it being syndicated, since it isn't a draw for cable networks when their potential audiences can watch it on Netflix instead.

Hanging over all this is "artificial intelligence" such as text-generation apps such as ChatGPT and computer-generated facsimiles of actors' faces and voices. The AMPTP is eager to use this technology to supplement, if not supplant, writers and actors. They refused to even negotiate with the WGA's desire for a ban on AI in scriptwriting. One of the straws that broke the SAG's back was a horrifying proposal by AMPTP to "scan" actors' appearances for perpetual ownership by the studios — the scanned performer would earn only a day's pay from the arrangement.

The C-suite embrace of AI ultimately goes back to residuals — if a studio generates a "script" with ChatGPT then hires a writer to make it into something filmable, then they can deny the writer residual payments on the resulting film/TV since they were "only" the script doctor. Under the AMPTP's preferred terms, using only an actor's digital likeness would mean no payout to the actor themselves since, technically, their appearance is the studio's sole property.

Which side are you on?

With SAG having just joined the picket lines, the strike is sure to continue. The longest writers strike in Hollywood history was the 1988 WGA strike, which lasted 22 weeks. If this strike continues until the end of 2023, as some have predicted, it will eclipse that record.

I'd say it's a sure bet the strike lasts beyond the end of the summer. While the WGA and SAG have both offered proposals (including alternative residual models) to the AMPTP and the public, the producers are preferring to wait the Guilds out.

This is why, even though SAG ending their strike first worked out in 1960, I hope the writers' and actors' Guilds remain striking until both unions have their futures secured. SAG members walking out gave the strike a second wind, both in putting more pressure on the AMPTP and boosting public awareness. Regular, non-industry folks know who the striking actors are, and they like them – many are taking advantage of that to create solidarity. Parasocial relationships might be used for some good for once!

Divide and conquer is one of the oldest strategies in the books, especially with strike-breaking — I hope and pray that the WGA and SAG can route any attempts to use it on them.

You can find resources on how to assist with the WGA and SAG strike here.