Jurassic Park's Creator Predicted The Strangest Part Of The SAG Strike In A 1981 Sci-Fi Movie

Predicting the future is wildly difficult; if anyone could do it, then there would be far fewer natural disasters and tragedies as well as a far richer citizenry, and so on. Yet that doesn't mean it's impossible — all one needs to do is read the proverbial tea leaves of history, trends, and technology, add a healthy dollop of that magic sauce known as human nature, and your predictions will tend to be more accurate than not.

Artists are preternaturally good at this type of alchemy as their job is essentially to observe human nature closer than most. Author and filmmaker Michael Crichton understood this task all too well. Folding into his numerous novels, screenplays, and short-lived filmmaking career is a myriad of predictions about where the final third of the 20th century was to take humanity, and beyond. Quite often, his observations were wild and lacked subtlety if only because Crichton was a consummate showman, sacrificing credulity for entertainment where he wished. After all, the task of bringing back to life the famously extinct dinosaurs for "Jurassic Park" is a big ask when it comes to reality.

Crichton's visions of the future had more truth to them than not, however, and today one was virtually proven completely true, full stop. As SAG-AFTRA officially moved to strike against the AMPTP, it was revealed that one of the movie studios' proposals to the union was to use AI to form a digital likeness of an actor to be used, as union negotiator Duncan Crabtree-Ireland explained, "for the rest of eternity with no compensation," possibly even past their actual demise. As it turns out, that proposal is the exact dastardly plot by the villainous corporations in Crichton's 1981 sci-fi thriller, "Looker."

From human beauty to digital ugliness

"Looker" is an overstuffed film, taking its initial premise and shooting off into all manner of genre goofiness. This is partially due to Crichton following his overactive imagination wherever it took him, but also due to his clever inception of the concept's far-reaching, troubling implications and potential applications.

The film follows Dr. Larry Roberts (Albert Finney), a successful Beverly Hills plastic surgeon who discovers that several of his patients — who are already extremely beautiful young women — are mysteriously disappearing after getting surgery at his practice for a number of minute, infinitesimal "imperfections." As he embarks on his own investigation of the disappearances, he's warned by one of his patients that these models are actually being murdered. In true Hitchcockian fashion, he pairs up with a young actress/model named Cindy (Susan Dey) to follow the trail of shady doings back to the company Digital Matrix, Inc., aka DMI.

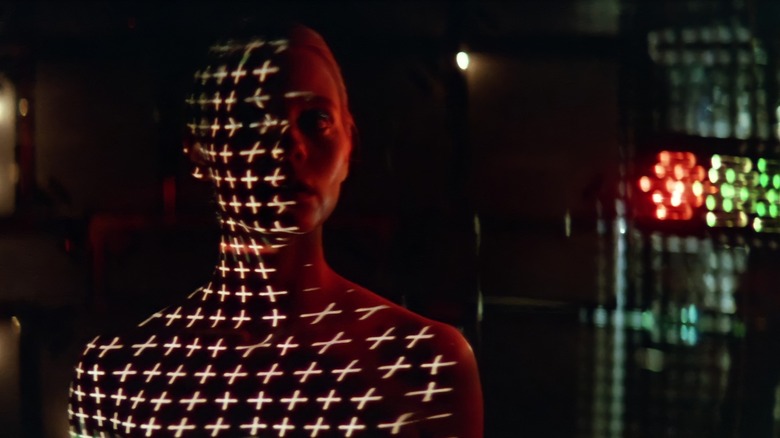

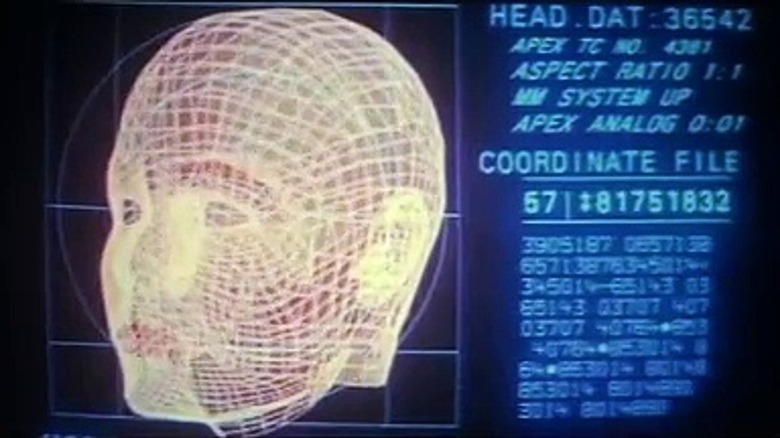

Crichton's story features a lot of extrapolated technology that riffs on the film's theme of perception, chief among them a Looker (Light Ocular-Oriented Kinetic Emotive Responses) gun, a device that puts a victim into a trance and allows an intruder or murderer to operate essentially unseen. Yet the film's most insidious concept is DMI's digital scanner, which turns every physical element of a person into a digital file that the company owns and can manipulate, including — in the film's case, especially — after that person's actual death.

The 'groundbreaking' idea of owning a person forever

During the press conference held by SAG-AFTRA, chief negotiator Duncan Crabtree-Ireland made public that one of the AMPTP's (alleged) ideas on the table was "a groundbreaking AI proposal that protects actors' digital likenesses." As Crabtree-Ireland made clear, however, the proposal actually was more along the lines of paying the likes of background actors for just one day of work, after which their digital likeness could be used by the studios however and for as long as the companies' wished.

As Crichton pointed out in "Looker," fair wages and compensation are only the beginning of this digital dilemma. In the film, the actors and models are first required to physically change their bodies to suit what DMI's viewer data says are the most attractive attributes possible. In this, there are shades of what's already happening to shows and movies on streaming services, where series and careers are being canceled because a given work doesn't fit some algorithm's "taste clusters."

The next step of the evil plan in "Looker" hasn't quite taken place in the real world yet, but we've gotten dangerously close to it. In "Looker," when actors like Cindy aren't able to hit their perfect marks, their work is given over to their digital double. Soon enough, doubles replace the now-deceased originals, forced to not only unscrupulously advertise whatever product DMI wants to sell, but with DMI making doubles of public figures — including politicians — using them as literal mouthpieces to their own ends.

The continued usage of "de-aging" technology in films and television is edging perilously close to this ghoulish possibility of using a dead person to perform in things that they may not have wanted to when they were alive, and the presence of "deep fakes" makes the possibility of putting lies in someone else's mouth that much more likely.

Take heed of cinema's warnings

There's an inherent understanding that fiction is often exaggerated for dramatic effect, and that goes double for genre material. The danger is using that fact as an excuse to diminish or dismiss the observations of a piece of art wholesale. To wit, contemporary reviews of "Looker" were not kind; Vincent Canby, writing for the New York Times, admitted that the film has a "promising premise" but that its "cautionary tale about science gone-mad is so full of narrative holes it could hold the interest of only someone with putty for a brain."

The other side of that same coin is the erroneous notion that a 42-year-old movie has nothing to tell us about our present. Sure, certain vaunted classics have reached a status of respectability that they'll often at least be considered, but so many other films — especially genre films — tend to be dismissed or, worse, laughed off the screen by jaded, modern audiences. Just look at the continual phenomenon of repertory screenings being hijacked by hecklers.

This attitude only helps the rich and powerful more easily get away with schemes that, like this AMPTP proposal, are nakedly, cartoonishly evil. In "Looker," the head of DMI is played by James Coburn (with a suitably devilish grin), and his antics are just as disreputable as more famous rich bastards like Mr. Potter (Lionel Barrymore) from "It's a Wonderful Life," Gordon Gekko (Michael Douglas) from "Wall Street," and so on.

Here at /Film, we've recently enjoyed pointing out the parallels between such characters and real-life people threatening the world with their greed. This "Looker" comparison throws all of that into even starker relief; here's a group of people who wanted to implement in reality what used to be yesterday's paranoid, evil fantasy. It's high time we all listen to artists like Crichton, respect the value of expertise, explore the rich veins of art history, and apply these lessons to our daily present, lest we wake up tomorrow and find ourselves permanently replaced by a damned computer.