The Audio Illusion That Makes Star Wars' Spaceships Feel Real

The "waa" sound of the lightsaber, the "pew pew" of the blaster, the roar of the TIE fighters, and the whoosh of the Millennium Falcon signal "Star Wars" to our brains. The man responsible for this (and using the very recognizable and hysterical Wilhelm scream in the films) is sound designer Ben Burtt. He created the soundscape for the "Star Wars" films as well as the first four "Indiana Jones" films, "E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial," "WALL-E" (where he also voiced M-O), and 2009's "Star Trek." He's won four Academy Awards and directed projects like an episode of "The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles" and "Blue Planet."

So many of the "Star Wars" sound effects are instantly recognizable, including the massive Star Destroyer as it moves overhead. (Save your debate about sound in space for another time.) Burtt took a few risks to create some of the sounds for the franchise, as he talked about in a 2020 interview with StarWars.com for the 40th anniversary of "Empire Strikes Back." They involved recording some real things in some dangerous areas.

Air races and WWII aircraft

To get the sounds for many of the ships, including the massive Star Destroyers, Burtt visited the National Air Races in Reno, Nevada. He explained:

"Back at that time there were few safety restrictions. We'd be on the runway, very near the zooming aircraft. I'd say, 'Hey, I'd like to record at the base of a racing pylon to get those 400 mph pass-bys,' and they'd say 'Yeah, OK. Just be careful.' I would hike out there and crouch down on the desert floor and planes would go by just a few feet overhead. You could smell the aviation fuel. They'd never let you within a mile of those pylons today."

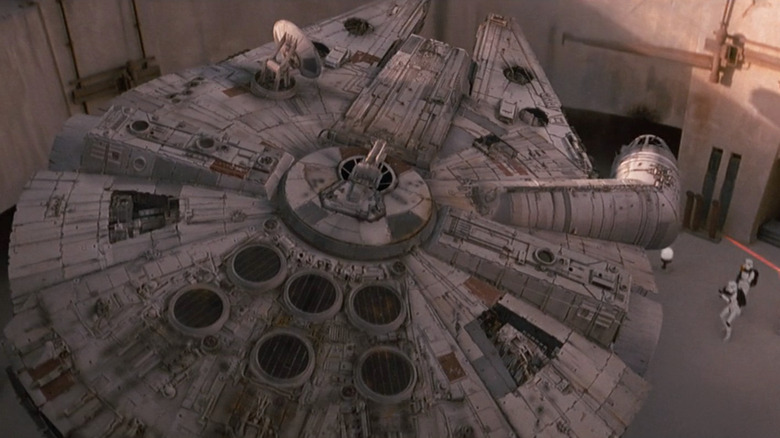

Yikes! That doesn't sound particularly safe, but it was pointed out in the article that it had to be done to accurately capture the sounds that we now associate with a space battle in a galaxy far, far away. Burtt also applied this to what is one of the most iconic ships in film history; the Millennium Falcon, as well as the TIE fighters. He said:

"We found that if we recorded a high energy piston aircraft — a World War II type aircraft — and slowed the recording down, you get a roar that people don't recognize. They hear a very solid Doppler Effect of something roaring by. It has a grinding energy to it, and people respond to the reality of that sound. They don't know what it is, but they realize it is real in some way, and that illusion is a key factor for all of the sound design in Star Wars."

The reason for the realness

When you hear that almost metallic roar of the TIE fighters, you can't help but immediately think of "Star Wars." It doesn't sound like anything else (even though it was). There is a good reason for some of these dangerous recordings. Creator George Lucas wanted the sounds to come from something real, according to Burtt. Lucas wanted it to "have an authenticity to it." Burtt said, "It would be real things, not something just electronic on a synthesizer or theremin, which was the tradition for science fiction previous to 'Star Wars.' That organic nature of the sound is the key basis for everything done in 'Star Wars.' That was really George's inspiration from the beginning so we got used to that approach." In that vein, Burtt actually used some of his own voice recordings of baby talk mixed with electronic sounds so that R2-D2 sounded less mechanical, according to Popular Mechanics.

Getting on a soap box here, but things that are grounded in some sort of reality, whether it be sound or visual effects, make for a better movie. It can be hard to listen to a created effect in either instance and not know on some internal level that it's made up. When you have a lot of things to "accept" in a film, like space travel, the existence of a power that unites the universe like the Force, and a universe where alien species haven't wiped each other out, anything we can cling to in terms of our own world makes the rest of it easier to accept.

All of the "Star Wars" films and TV shows are streaming on Disney+.